Enjoy this post by Arusa Malik, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2022-2023 academic year.

When I began as a Freshman Fellow, I was drawn to the cartoons and comics that were sprinkled across the world of Women’s Liberation. Growing up, comics and graphic novels were my escape from reality. Soon comics like She-Hulk and Squirrel Girl became an addiction. Everyday women defying odds and making the world a better place…what little girl wouldn’t be inspired?

My goal throughout the freshmen fellowship was to understand women’s suffrage and liberation through the lens of popular culture. What began as a simple interest in the politics of gender and comic books quickly turned into a yearlong endeavor, diving deep into the creative ways women fought for their rights. From exploring the importance of hat styles in the fight for a vote to reading satire-stuffed articles that criticized the suffragettes, I was exposed to both sides of the story in completely unique ways.

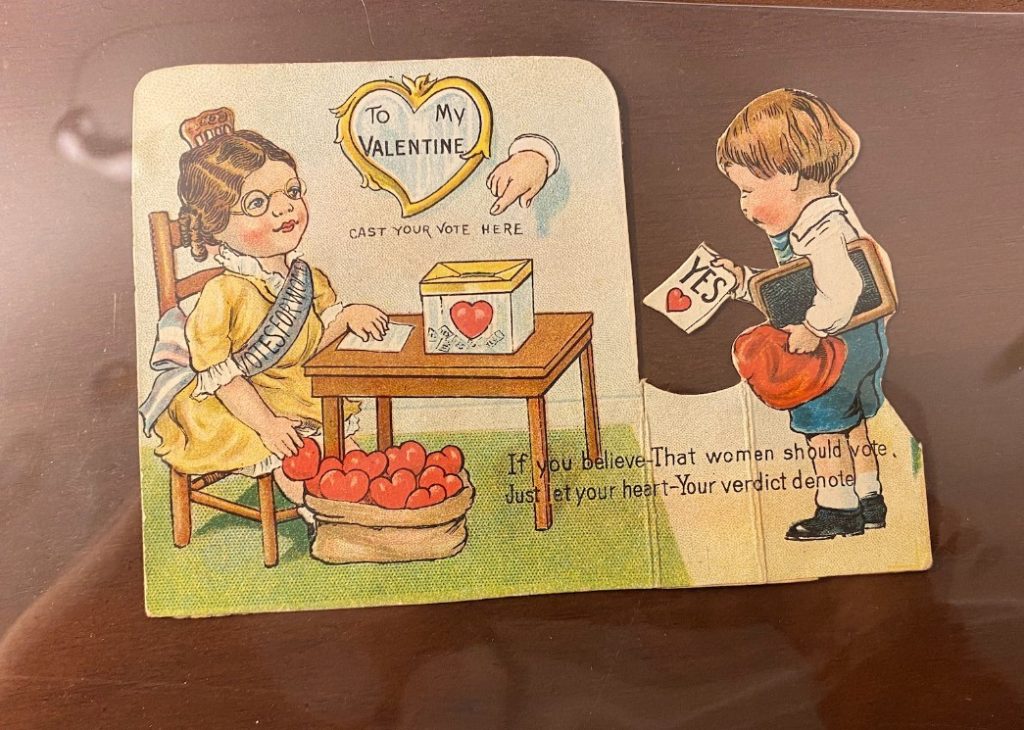

When I began researching the suffrage and liberation-related artifacts at Special Collections, I noticed the plethora of symbols used to excel women’s issues. Cats, children, feathered hats, and roses were all symbols suffragettes used to convey their message undercover. Soon, as the movement became more public, these symbols were found everywhere.

Continuing on with my research, the mediums used by suffragettes were incredibly unique. From the classic lapel button to hilarious postcards. The suffragettes certainly were not short of creativity. In particular, I admired the suffragettes depiction of men in many of these instances. Rather than viewing men as grisly oppressors towards women, suffragettes painted men as supporters of the movement who had the best interest of women at heart.

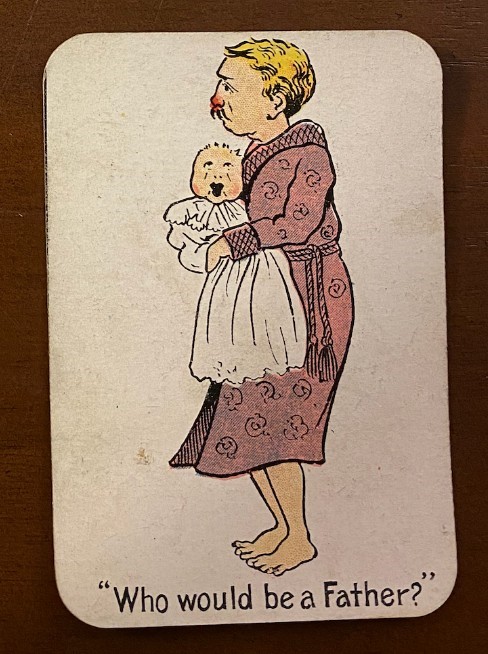

The anti-suffragists were creative in their own right, using popular card games and propaganda-filled images to convey their message.

Oftentimes, the anti-suffragists would depict men as more “feminine” or subservient to women as a result of greater rights. Men would be illustrated as the primary caregiver of the home, dressed up in aprons and carrying a baby. Or the suffragists in images would have wildly exaggerated features to appear abnormal and undesirable.

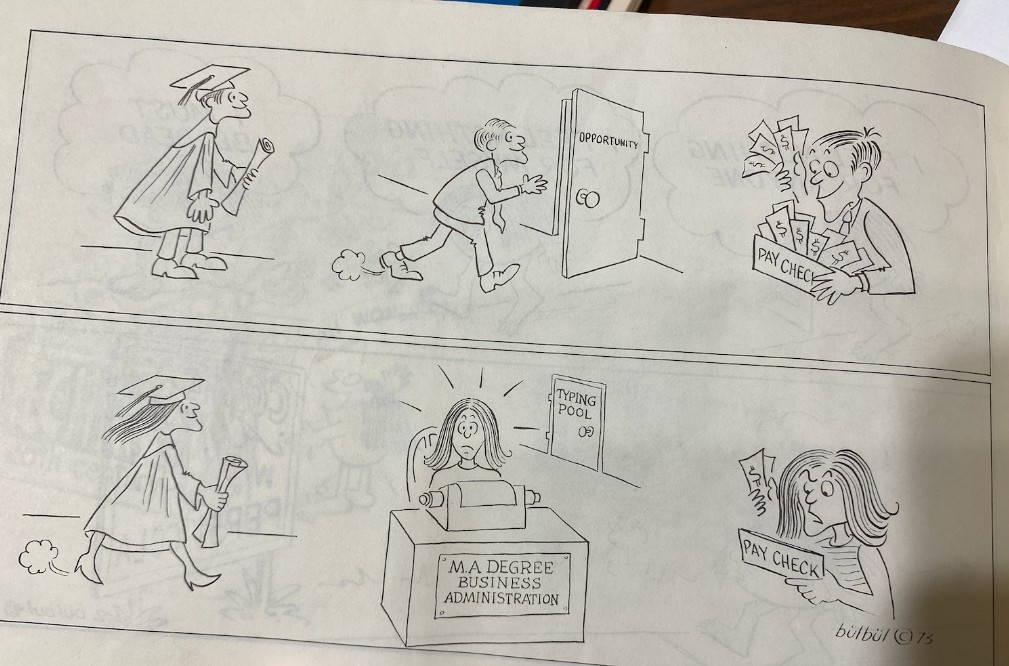

Interestingly enough, spending time observing both the popular culture produced by those who supported the fight for women’s and liberation..and those who didn’t, allowed me to come to conclusions about each side. Women’s suffrage is all about equality. It seems obvious enough. Women were denied rights for hundreds of years and in order to provide more of a say to the policy making process, community building initiatives, and modern society in general…they needed to have equal footing to men. For a long time, standards in society were set by men. The norm is what men have, therefore women become inferior to men. This “male standard” is explained perfectly by Catharine MacKinnon in Difference and Dominance: On Sex Discrimination. She explains how “[women] are measured according to our lack of correspondence with man, our equality judged by our proximity to his measure”.

You might be wondering, Arusa, how does this connect with the suffrage movement and popular culture? Understanding this male standard, and how women’s progress in society has been judged, allows us to understand where the anti-suffragists are coming from. Exploring the artifacts in Special Collections and reading literature on gender dynamics this year has allowed me to understand that the anti-suffragists didn’t simply disregard women (although many were misogynists and some did). They were afraid of women overpowering men, overthrowing the male standard that society has maintained for so long

This, in no way, is said to sympathize with anti-suffragists. Rather, it is meant to help us understand how those who did not support greater freedoms for women could have their mind changed.

During the end of the year, I read many women’s liberation books that were aimed towards younger audiences. Short comics and large-font picture books with lots of color. Seeing how authors boiled issues down into bit-size, digestible, pieces inspired me to create a short comic that highlighted the symbols used during the liberation movement and better understand the opposition towards the movement.

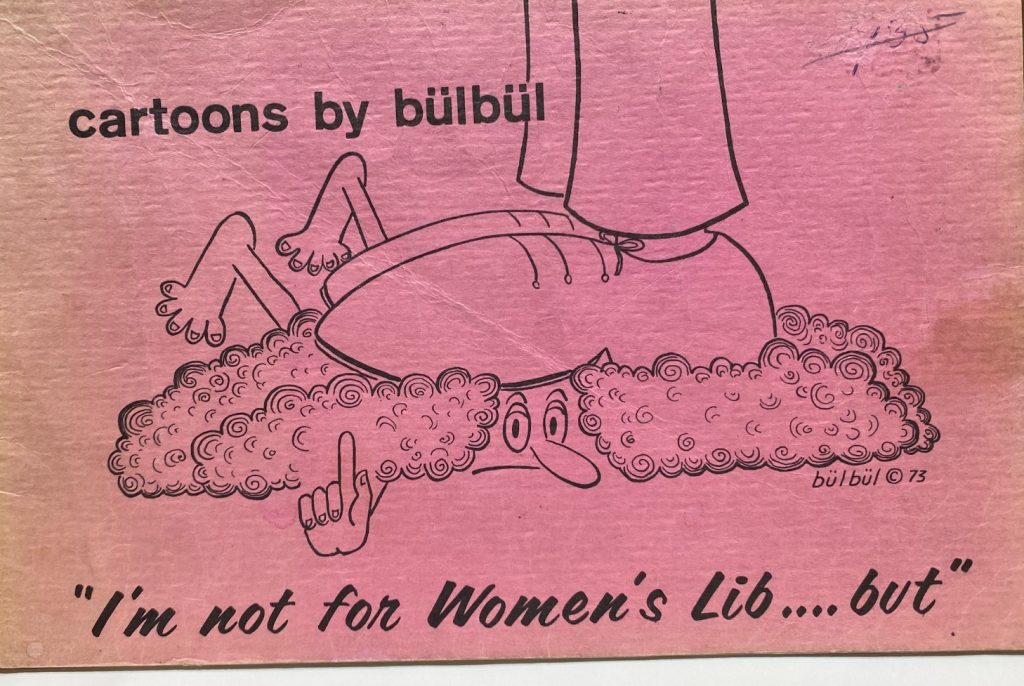

I drew inspiration from “I’m not for Women’s Lib…but” by Bülbül, which shared simple scenarios of how capitalism has oppressed women, beginning at the end of the 20th century. Scenes including the sexualization of women’s bodies and the gender-wage gap were depicted in simple, one-page, drawings.

I was also drawn to the intricate fashion symbols the libbers used to subtly, but effectively, draw support in for their cause. One artifact called “Hatbox” stood out to men, as it was an accordion style drawing book that showed the various flamboyant hats suffragettes wore. In my short comic, I drew inspiration from “hatbox” while dressing Alice Paul, a key figure in organizing the Women’s Suffrage Marches in Washington, D.C. prior to Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration.

When creating my final project, I wanted to come full circle to my interests. I chose to create a short, ten-page comic that displayed some of the key aspects I absorbed during my research. For my final project, I wanted to create something that even a young child could enjoy and learn from. I tried my best to tap into my inner fifth grader while doing this.

My comic, titled “Penny the Libber versus the Male Chauvinist Pig ” follows a young Penny who is chasing a male chauvinist pig (a literal pig, also known as the MCP) who is wreaking havoc wherever he goes. The MCP jumps through eras in the 20th century, attempting to sabotage key moments in American women’s history, with Penny right on his heels. Throughout the comic, I tried to sprinkle important symbols of the movement including feathery hats and roses, and include themes I picked up while researching rare artifacts.

I am so grateful for this fellowship, as it has allowed me to research in ways I didn’t know were even possible. I would like to thank my fantastic mentor, Heidi Herr, for all her guidance. From pulling artifacts out of Special Collections to guiding me with my final project and providing me with the literature I needed to do my own consciousness-raising, I would not have done this without Heidi’s help.