Enjoy this post by Arusa Malik, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2022-2023 academic year!

Bam! Pow! Crash! Thump!

When I think of these classic onomatopoeias, I am instantly brought back to the countless hours spent under the covers with the latest edition of Archie, Betty and Veronica, or Big Nate. For many of us, comic books were an escape away from reality. The captivating story arcs, comedic relief characters, and vivid animation subconsciously shaped who we are today.

Although comics have historically been a source of entertainment for readers, they were used for a new purpose in the 20th century: A tool in the fight for women’s liberation.

Before we begin diving too deep, please allow me to introduce myself. My name is Arusa Malik, I am hoping to study International Studies and Political Science in the School of Arts and Sciences, and I have been honored to be conducting research with Special Collections and Archives as a Freshman Fellow.

To preface, what we consider to be the women’s liberation and suffrage movement truly took off towards the end of the 19th century. In fact, the movement’s roots can be traced back to the Seneca Falls Convention or the first women’s rights convention in New York. As issues regarding equality and the right to vote were discussed, a greater movement regarding the liberation of women was arising.

During this time, women would famously rally together and protest the oppression they were facing. As we move more deeply into the 20th century, mothers who were forced to stay within the confines of their home, underpaid office workers, and advocates for abortion access were just a few of the different women you may have found actively participating in the movement. However, beyond the “classic” activism that came to mind (think protests and mass gatherings) popular culture came to be a key player in the fight for feminism.

“Consciousness raising”, a term coined during the 1960s, was the idea of activism through increasing social awareness. What better way to conscious raise (yes, I’m using it as a verb) then by spreading information through everyone’s favorite pastime activities. All of which include comic books, playing cards, postcards, and board games.

Oftentimes, comic illustrations or books that portrayed situations of women overcoming the patriarchy or achieving a goal (such as obtaining a dream career or finding self-satisfaction) outside of love interests were used as a medium of empowerment. For instance, feminist political cartoons by Lou Rogers published in the humor magazine Judge depicted women strong in body and spirit.

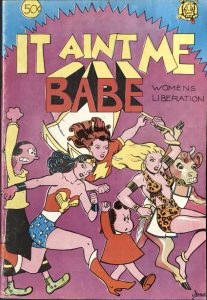

Let’s move forward sixty years and take a look at the iconic women’s liberation comic It Ain’t Me Babe.

The idea for this compilation, first pitched by Trina Robbins, came from frustration regarding the depiction of women as sexual objects and tools for men to “collect”. For years, bits in newspapers and larger pieces in comic books were written by men for men. The initiative to write It Ain’t Me Babe began with several women, led by Robbins, who worked as unpaid volunteers. Their goal was to create an original compilation of stories that would uplift women and alter the perspective of men. After the original draft, the women behind this comic advocated for the pilot publication of their first volume. Soon, as demand for the first edition skyrocketed, subsequent publications were warranted.

One of the first stories in It Ain’t Me Babe, titled “Oma”, depicts the bravery of a mother and wife, as she reunites with her murdered family. Paradoxically, this story was one of the first situations where a woman was portrayed as the “heroic” main character and her husband as the “victim”.

Outside of the plot breakthroughs seen in that particular comic, there are a variety of symbols depicted through humorous postcards and board games that were directly linked to the women’s liberation and suffrage movements.

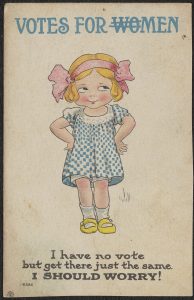

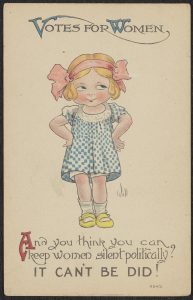

Children were often used to represent innocence and purity, a symbol used by both suffragettes and anti-suffragists to depict different messages.

You can see the juxtaposition between the anti-suffrage and pro-suffrage postcards. These commercial postcards published by New York-based publisher S. Bergman around 1913 were part of a series featuring pro- and anti- suffrage messages. In the example above, both utilize the same image of a young girl dressed like a child suffragette. Suffragettes were known for wearing elaborate hats or headgear that would make it so they were easily identifiable, just like the bows this young girl adorns. In one image, the caption reads: “And you think you can keep women silent politically? It can’t be done!” Showing the resilience and strength the suffragettes hold. On the other hand, the opposing postcard reads: “I have no vote but get there just the same. I should worry!” (note the crossed out words at the top that turn “votes for women” into “votes for men”). This card highlights what anti-suffragists claimed to be a lost cause; they understood the women’s suffrage movement and other issues pertaining to women and liberation more broadly to be useless and unnecessary in the grand scheme of things.

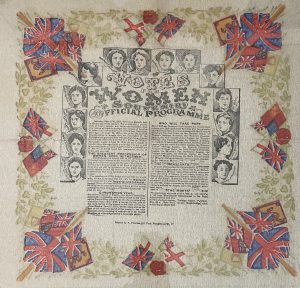

If you thought the suffrage movement was contained to comic postcards, I am afraid you’ve been mistaken! The suffragettes were incredibly creative women and made sure nothing went to waste…including napkins. Just as comics were used to share the story of strong women, souvenir table napkins did the same. In 1911, the Women’s Social and Political Union of England organized the Women’s Coronation Procession which was planned right before King George’s coronation ceremony. Their goal? Demand women’s suffrage at the hands of a new monarch. The two and a half hour long march was advertised primarily through printed methods, which included napkins.

This “souvenir official programme” napkin was distributed to women across London to encourage them to participate in suffrage activities. It clearly outlines the purposes of the processional, the location of the processional, and who is invited. Such creative methods of advertisement were not uncommon, as activists were required to think out of the box in order to have their message heard.

What I have shared with you here barely scratches the surface of popular culture in the women’s liberation movement; there are quite literally hundreds of comics, games, cards, photographs, and artifacts to explore! I would like to thank the staff at Special Collections and Archives for facilitating a supporting space for me to research. I would also like to extend a massive thank you to Heidi Herr who is currently mentoring me as I navigate the various artifacts within Special Collections.

Moving forward, my goal is to better understand the intersectional relationship between popular culture and the growth of the liberation movement, along with how popular culture has evolved throughout the 20th century. In the meantime, I hope you can partake in your own consciousness raising!