During my sophomore year of music school, I took a class in earth science. There I learned about the loudest sound in recorded history—the 1883 eruption of the Krakatoa volcano that was heard 3,000 miles away. To put the distance into perspective, that would be the equivalent of an explosion in Seattle being heard in Baltimore. A subsequent report found that the eruption could be heard across one thirteenth of the earth’s surface. Since a new volcano in Iceland has also been in the news lately, I thought this would be a good week to dive into the Levy collection’s volcanic holdings.

Where Are Now the Hopes I Cherished was published by Oliver Ditson in Boston, undated but likely from between 1830-1850. The song comes from Bellini’s opera “Norma” (it was quite popular for European classical songs to be translated into English and reproduced in the United States). The lithograph shows a couple standing in front of a series of ruins with a smoldering mountain in the background. The lithograph is quite detailed, although the face details are not the most impressive.

It’s unclear why there’s a volcano in the background here—Norma doesn’t have a volcano in the plot, although there is a storm (the opera is set in Gaul, 50 BCE). Instead, it seems the mountain is a metaphor for the destruction described in the lyrics: “Where are now the hopes I cherished? Where the joys that once were mine? Gone forever! All have perished, and the ruin thou hast made.”

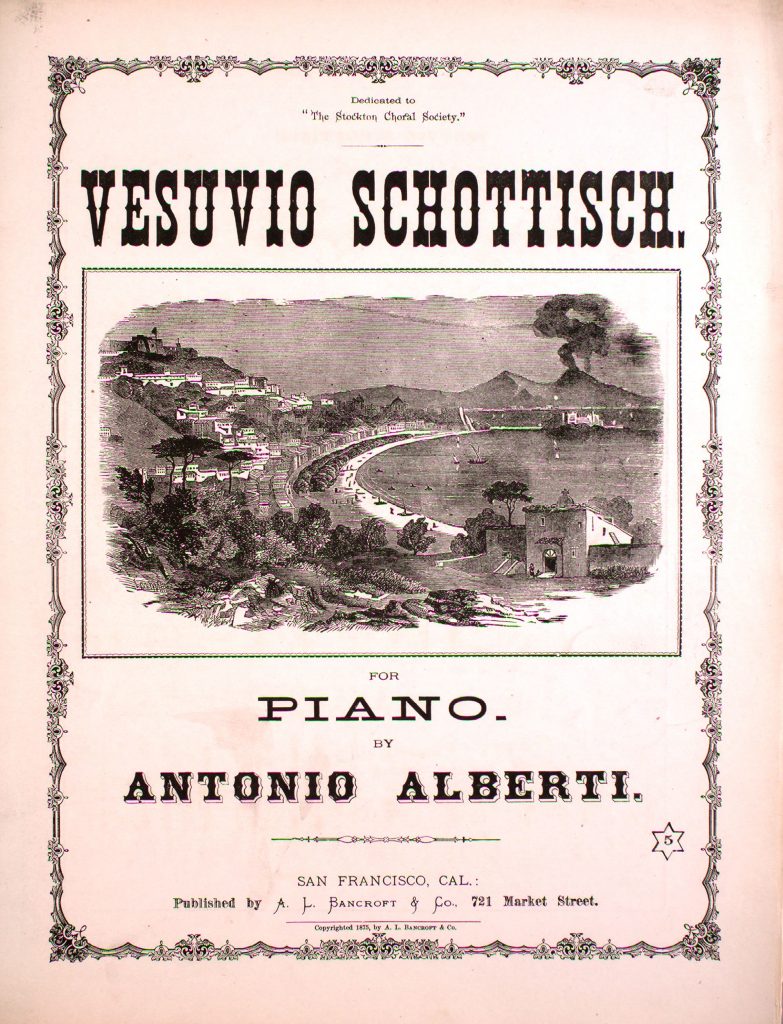

“Vesuvio Schottisch” was published in 1875 in San Francisco, a city less popular in sheet music than the East coast hubs of New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Mount Vesuvius can be seen in the background of this lithograph, presumably during its notorious eruption in 79 AD when it destroyed the city of Pompeii and others. The perspective here appears to be from North of the volcano, potentially in Naples. The music has no text, but sections of the music alternate between raucously loud and delicately soft, mimicking the violence of an eruption. Music like this that attempts to replicate real-world phenomena is often called programmatic music or program music (another good example is Tchaikovsky’s famous 1812 overture, which incorporated actual cannons into the percussion section).

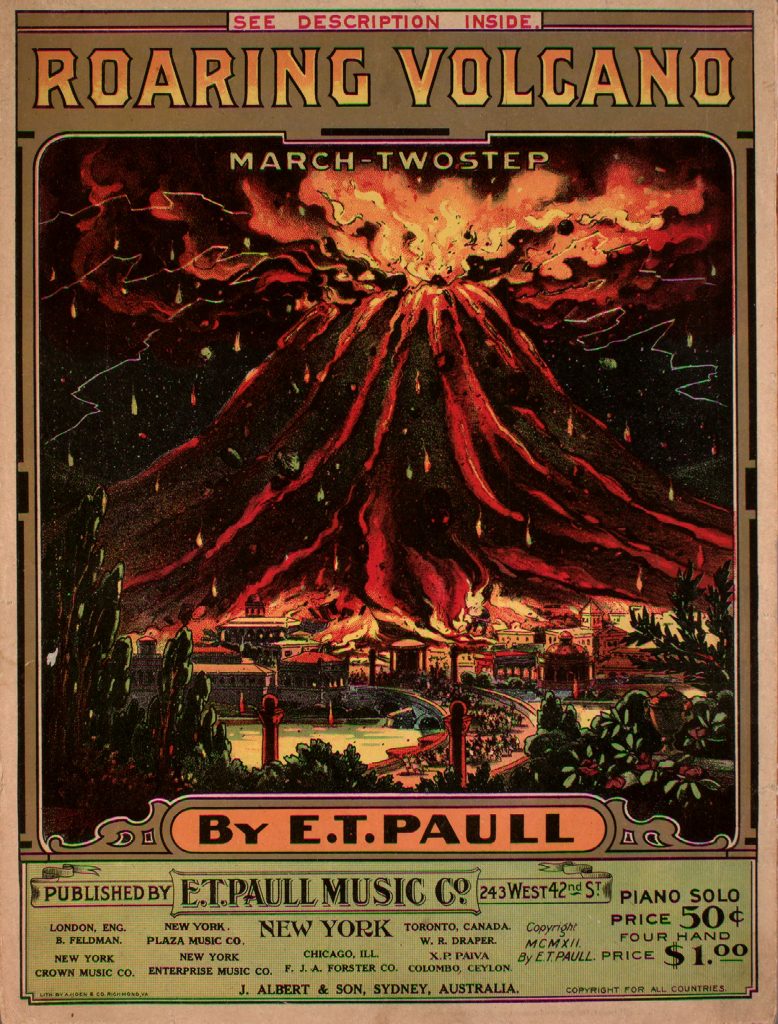

The eruption of Vesuvius is described even more programmatically in “Roaring Volcano” by E.T. Paull, published in New York in 1912. The cover shows people fleeing over a bridge as the volcano shoots ash and lightning into the air. Paull also added descriptive phrases throughout the song to indicate which events correspond to the music. The song starts with trumpets sounding as the Olympic Games begin. Next comes the volcano’s distant rumble, which increases until it erupts “in full fury.” The next section is marked triple forte, or fortississimo—one forte means ‘loud,’ so you can use your imagination (a full recording can be found here).

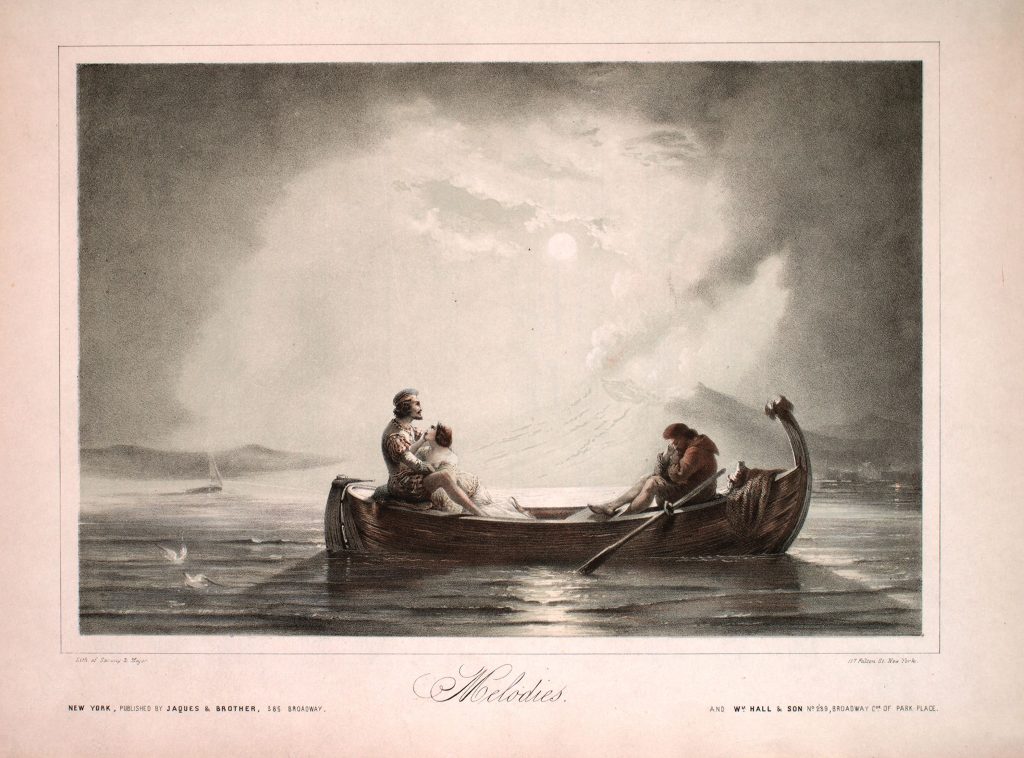

This lithograph took my breath away. The nuanced shading and light, the detail of the boat and shadow behind it, and the colors of the figures’ clothing make this cover a captivating work of art. This song is also undated, but it was likely published before 1860. The lyrics don’t mention a volcano at all—the couple sings to each other about how the spirit of love watches over them. The figure on the right side of the boat, responsible for rowing, seems to have given up. Perhaps then the couple is attempting to escape the disaster behind them and realizing they may not succeed.

As volcano watching has become the latest tourist attraction in Iceland, these mountains will no doubt continue to inspire artists well into the future. However, for those of us that don’t wish to peer into a crater, Werner Herzog has a stunning documentary on volcanoes called Into the Inferno.

As the curator of the Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection, a phrase I hear often is “I didn’t know sheet music could be used to study…”

Levy collected 30,000 songs over 50+ years not to perform, but to use as a lens for studying history. To make this easier, Levy organized his collection by subject, rather than title or composer. As a result, there are hundreds of unique subjects that can be used to filter the collection. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to dive into some of the more fascinating, obscure, and strange subject headings in the collection. Each week, I’ll focus on a different subject — stay tuned for more deep dives! You can view the entire digitized collection here.