Enjoy this post by Ivy Xun, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2019-2020 academic year!

The passage of the 19th amendment marks 2020 its historic centennial, while the present draws the year into a time of pressing uncertainty. Covid-19 continues to devastate along the curve, exposing health disparities at every level, in rising fatalities and crushing unemployment. Still, this year is as much a narrative of suffering as it is of resistance: May Day essential worker strikes, insurgent Black Lives Matter protests, local acts of generosity.

Covid-19 has renewed conversations around our health infrastructures and economic ideologies, conversations that echo those a hundred years ago, when suffragists justified the role of women in the public sphere by redefining public health as civic housekeeping, when writers and activists in the Woman’s National Committee (WNC) of the Socialist Party leveraged socialism to campaign for the right to vote. And Black Lives Matter marches across the world calling attention to systematic racism and police brutality reveal the continuing legacy of protest and violent confrontations with the state, a legacy seen in the Occoquan Workhouse and the 1910 Black Friday demonstration in London for women’s right to vote. Still, it is important to acknowledge, historically, who had access to violence as a means of admissible political activism, and who was excluded from political movements and how.

What I mean to say is, I don’t think there’s a time for reflection on the women’s suffrage movement that is more relevant, timely, and profound, than now. Since my last blog, I’ve decided to focus research on accounts of violence in suffrage ephemera. In underground pamphlets, once-glossy postcards, and magazine exposés, I examined how they attempted to answer how women ought to act, advocate, protest. Here are some of my favorites from the collection:

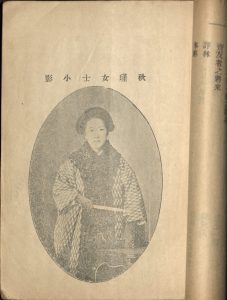

Qui Yu Qiu Feng (Autumn Rain, Autumn Wind) Memorial for the Executed Revolutionary Qiu Jin 1907

This pamphlet, written in Mandarin, features a portrait of Qui Jin, a Chinese revolutionary, writer, and poet. She criticized arranged marriages and foot-binding and advocated for better schooling for women in early 20th century China. In 1907, she was executed. Most pages in the pamphlet have faded, some are stained, all are a reminder of how the very printing of this pamphlet was itself an act of rebellion, and how extraordinary it has been preserved. On the lower wrapper of the pamphlet is a hidden gem, my favorite part: a 1922 “Paid” stamp from a San Francisco Chinese grocer. How did such an underground, risky publication land itself in California? The answer’s unknown, but the question points to how interconnected and international the women’s suffrage and feminist movements were, with ephemera exchanged cross-boundaries.

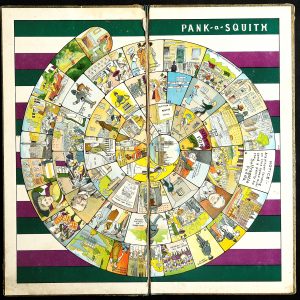

The Women’s Social and Political Union in 1909, a militant wing of the British woman suffrage movement, created this board game as a fundraising item. Green, white, and purple, the colors of the WSPU, stripe the background and slip in game spaces on flags, sashes, and hats. The board game doesn’t shy away from violent acts committed by suffragettes, featuring women smashing windows along streets in protest and suffragettes’ confrontations with police. Game spaces also feature women engaging in political theater to advance the suffrage cause, rallying together to celebrate suffragettes released from prison.

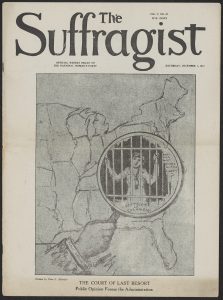

The Suffragist, Vol. V, No. 97, 1917

The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage published The Suffragist weekly, and this particular issue spotlighted 31 suffragette prisoners in the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia. The 31 hunger-striking suffragettes, ranging in age from 19 to 73, were forcibly fed and beaten by guards. The issue published prison notes from one suffragette, Rose Winslow. She writes, “The feeding gives me a headache. My throat aches afterward, and I always weep and sob to my great disgust, quite against my will.” Here, media coverage on the violence involved in the fight to vote is necessary to understand the brutal, and often understated, underpinnings of the American women’s suffrage movement.

True to the word “unprecedented” that lingers in almost every mention, Covid-19 has definitely upturned expectations on how freshman fellows would continue spring semester. Deadlines have shifted, conferences postponed, research moved online. Though most of the materials in the collection are available to view on Flickr, I miss my visits to Special Collections and its glassy space of quiet, thumbing through materials and enraptured in the physicality of it all: the yellowed pages, the scribbled margins, the idea that discovery was something you could hold in your hands.

I’ve been incredibly lucky to be a part of the Freshman Fellows program this year. I’m still learning how deeply complex the women’s suffrage movement was; how it was a movement of contradictions, of exclusion and insurgent voices of women of color, of tension and humor, of subverted and perpetuated gender norms. As of now, my research partner Aarushi Krishnan and I, with the help of our amazing mentor Heidi Herr, are working to complete an online exhibit to showcase the collection. I look forward to sharing our final project with you all – stay tuned!