Note: This blog post includes images and content related to the killing and preservation of animals for scientific and artistic purposes.

“Fixed up museum. . . . I catalogued about 75 of our bird skins. . . . I am getting to skin better than I used to and hope soon to be an expert.”

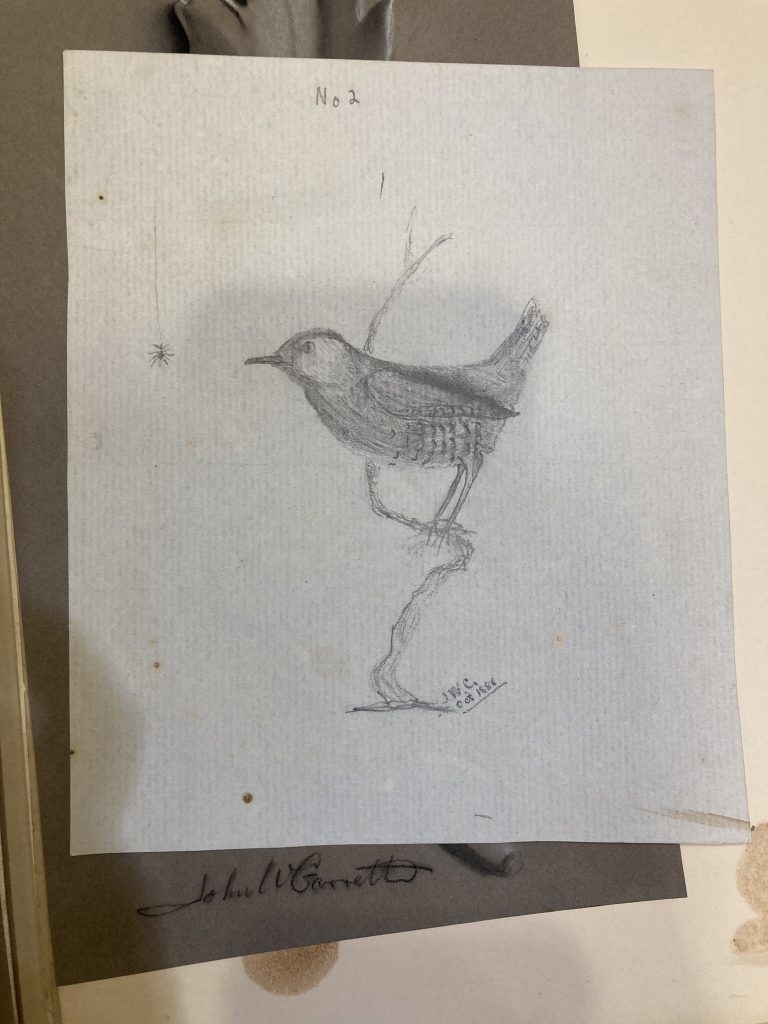

—16-year-old John Work Garrett in his journal, autumn 1888.

John Work Garrett II (1872-1942) was a lifelong bird enthusiast and he created and collected specimens for a collection of natural history at Evergreen. Garrett sought lessons from professional taxidermists and collected books on taxidermy crafting to better identify his own style.

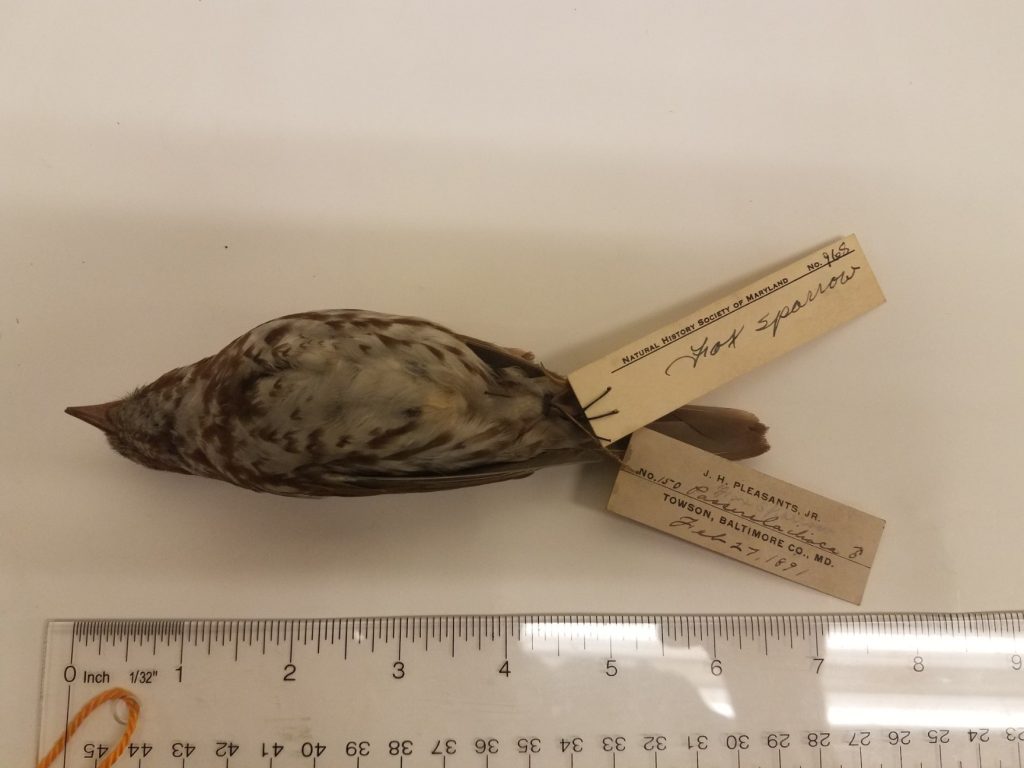

At the peak of his specimen collecting in the late nineteenth century, taxidermy was a common way to distribute specimens for educational purposes. Study skins, when a specimen’s skins, feathers and/or fur are preserved for scientific research, were especially useful for bird enthusiasts. Mounted taxidermy, when the animal is posed in a way to look lifelike, was especially popular among a general public, particularly at natural history museums. While not necessarily scientifically beneficial, making the animal look lifelike in mounted taxidermy models tended to be more comfortably received by the general public than skins.

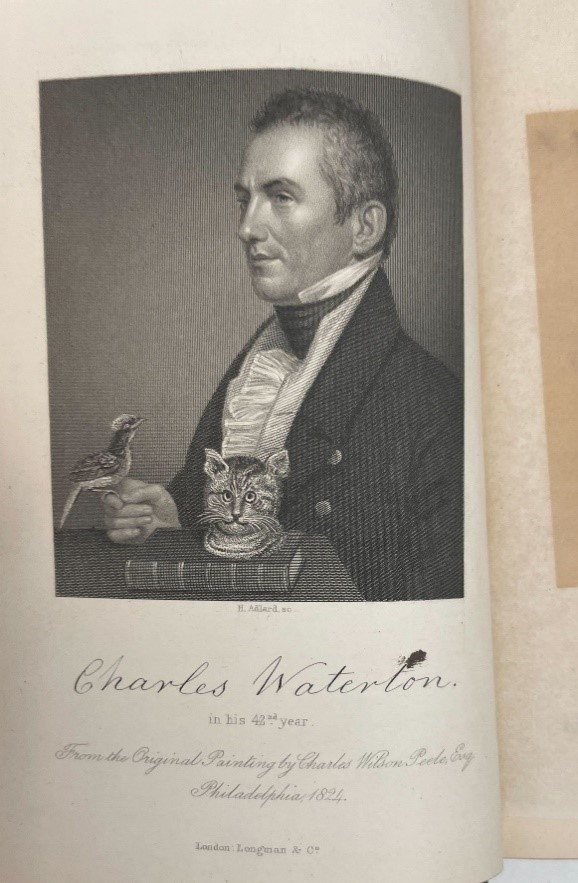

One of Garrett’s favorite taxidermy artists was Charles Waterton, who he referenced in his journal, writing, “Read Watertons [sic] Wanderings on South America. . . . he must have been a good taxerdermist [sic]. His method is very good. He skinned a bird almost the same way as I do, except he always takes out the skull.” Waterton was an eccentric conservationist in the early nineteenth century who spent his life living between Yorkshire, England, and South America. His style of taxidermy involved soaking the specimens in what he called “sublimate of mercury.” Rather than stuffing the taxidermy, his specimens were hollow, giving them a lifelike appearance.

While Garrett created skins and taxidermy for his collection, he also purchased taxidermy and furs as souvenirs from his trips West to remember his excursions by and to decorate his home, noting just halfway through one summer in 1894 that, “Our fur bill now amounts to $450.00. Surely we are a godsend to the taxidermist!”

At home at Evergreen, Garrett referred to his natural history collection as his “museum.” While his wife, Alice Warder Garrett would create an Evergreen remembered for its collection of fine and decorative arts, John Work Garrett had been actively curating collection focused around the artistry of natural specimens, collaborating with the natural world as a fellow artist.

While taxidermy for the purposes of education was certainly widespread among the professional and amateur scientific community at the turn of the twentieth century, there was also a practice of taxidermy as a means of over-hunting for recreational or political purposes. At the time that Garrett went west in the 1890s, it had become apparent that the overconsumption of this style of hunting was rapidly damaging the American natural landscape. In response, hunting groups like the Boone & Crockett Club, of which Theodore Roosevelt was a part, became some of the first conservation advocacy groups, seeking sustainable game hunting practices and habitat conservation in the outdoors. They assembled the National Collection of Heads and Horns as taxidermy that made a statement, dedicating the collection “In the Memory of the Vanishing Big Game of the World.”

Interested in learning more about John Work Garrett, his trips West, or want to see some 1890s study skins in person? Come visit Evergreen Museum & Library’s exhibition, Leave No Trace: John Work Garrett in the American Outdoors, on view until June 8, 2025!