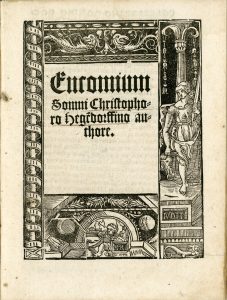

My name is Lucy Massey, and the focus of my Freshman Fellows project is to improve my Latin skills by translating a selection of rare texts from the George Peabody Library of The Sheridan Libraries. The piece I am currently working with is titled Encomium Somni, or In Praise of Sleep, by Christopher Hegendorff.

Printed and published in Leipzig in 1519, Hegendorff’s work, all of seven pages, uses Sleep as an anthropomorphic narrator. We first learn the genealogy of Sleep, who tells us: “Natus sum itaque nocte patre & lethe matre parentibus vel multo nobilissimis. Neque a fletu, ut quidam ait, vitae meae limen ingressus sum, sed statim cum risu.” And in translation: “Thus was I born to the most noble of parents by far, night as a father, and forgetfulness my mother. Nor did I cross the threshold of my life with wailing, as some say, but in an instant and with a laugh.” This playful personification of sleep is all the more striking given the works for which Hegendorff is better known – works of a religious and scholastic nature.

Through modern reference works in the Eisenhower Library, I have learned more about the author’s biography and how it may have shaped his work. Born in Leipzig in 1500, Hegendorff was at work on a Master of Arts degree at Leipzig University, and all of about nineteen at the time he wrote the Encomium Somni. He had also just written a very different sort of encomium, one praising Martin Luther. Hegendorff eventually taught a variety of subjects, including theology, civil law, and classical literature. His religious thoughts, writings, and personal affiliations are difficult to pin down, indicative of the academic culture of early humanism and the religious climate during the formative years of the Reformation. He was invited, for example, by the bishop of Poznan in Poland to teach at the university there, but left after a conflict with the archdeacon, who accused him of Lutheranism. Hegendorff briefly worked as a lawyer in a town on the modern-day German-Polish border, then served as a legal consultant to the city of Lüneberg in northern Germany.

Like his most learned correspondent, even ancient Greek authors such as Homer are kept alive in Hegendorff’s work. The Encomium is peppered with allusions to the Iliad and other Greek works, with quotations printed in the original Greek, as we can see here on the first page.

I n translating Hegendorff’s work, it has become clear to me the ways in which Latin was adapted to suit the needs of different times, even as ancient core texts were preserved. Hegendorff certainly does not read like Virgil or Caesar, but they share a common understanding of the spirit, practice, and dynamic use of the language. As someone seemingly so far removed from these writers, it has been endlessly exciting for me to feel connected to them through Latin.

n translating Hegendorff’s work, it has become clear to me the ways in which Latin was adapted to suit the needs of different times, even as ancient core texts were preserved. Hegendorff certainly does not read like Virgil or Caesar, but they share a common understanding of the spirit, practice, and dynamic use of the language. As someone seemingly so far removed from these writers, it has been endlessly exciting for me to feel connected to them through Latin.

Another avenue of my research has been reading the book Latin: Story of a World Language by Jürgen Leonhardt, a German professor of Classical Philology. Leonhardt draws our attention to what my research project has begun to show me first-hand: Latin had a long and illustrious afterlife. Unlike Babylonian or Etruscan, Latin became a truly global language, valued and taught for centuries after the Roman Empire fell. During the so-called ‘Dark Ages,’ Latin flourished as the language of academics, physicians, and scientists – as Leonhardt points out, the Latin writing from ancient Rome only comprises “at most 0.01 percent” of the total extant works written in Latin. In fact, Renaissance neo-Latin works, such as Hegendorff’s Encomium Somni, are not merely sleepy by-products of a once vibrant antiquity, but instead form an understudied wellspring of Latin expression. These learned works, as Leonhardt further argues, present a unique synthesis of ancient inspiration and contemporary innovation. Latin allowed scholars to communicate with each other and engage with the work of their predecessors across lengthy geographic and temporal borders. As vernacular languages developed for everyday use, Latin was never just brushed aside – those who read and wrote it recognized its power of a world language at a time when international communication was becoming increasingly fragmented by vernacular literatures and national interests.

Some of the challenges facing the would-be translator of these neo-Latin works in their original printed format include unpacking the prominent use of abbreviations by the type-setters (as one can see again at use on the first page); topical and learned allusions that are not always obvious; the inability to check earlier translations (as one could do for more canonical writers, for example); and, finally, a Latin syntax which seeks to model itself on the ancients, but has its own latter-day particularities. As I continue delving into rare texts at the Sheridan Libraries, I look forward to new discoveries and insights while I work to better my Latin skills.

Latin was at the crux of each of Hegendorff’s careers, as was the case for his peers, pupils, and predecessors. Throughout the Encomium Somni he makes learned allusions to contemporary authors who also wrote in Latin, such as Ulrich von Hutten and Desiderius Erasmus. Hegendorff actually wrote Erasmus a letter, unfortunately no longer extant, though Erasmus’ reply has come down to us. A good next step in my research will be to track down Erasmus’ response for a better understanding of the context of their relationship.