Fanny Milton Trollope (ca. 1780-1863), the mother of the esteemed writer Anthony Trollope, was herself a popular and successful writer in the 19th century. Her work was so popular on both sides of the Atlantic that the term “Trollopian” was coined to describe works of literature or situations that were reminiscent of her writings; the term today, however, is used when referring to works written by her son, Anthony. Her biting travel book, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) was so sensational that literary critic Henry T. Tuckerman commented that it became common for any transgression of proper etiquette to be “hailed with the instant and vociferous challenge, apparently undisputed as authoritative, of ‘Trollope’!”

Fanny Milton Trollope (ca. 1780-1863), the mother of the esteemed writer Anthony Trollope, was herself a popular and successful writer in the 19th century. Her work was so popular on both sides of the Atlantic that the term “Trollopian” was coined to describe works of literature or situations that were reminiscent of her writings; the term today, however, is used when referring to works written by her son, Anthony. Her biting travel book, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) was so sensational that literary critic Henry T. Tuckerman commented that it became common for any transgression of proper etiquette to be “hailed with the instant and vociferous challenge, apparently undisputed as authoritative, of ‘Trollope’!”

Though the majority of her work is largely forgotten today, she was a popular and influential writer of her era and wrote several books that continue to merit critical acclaim. Several works written by Fanny Trollope are available in Special Collections, including The Vicar of Wrexhill, The Life and Adventures of Michael Armstrong Factory Boy, The Life and Adventures of Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw, and The Widow Barnaby.

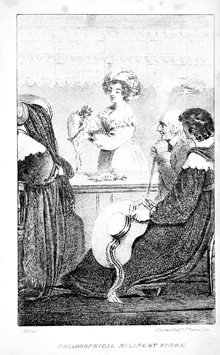

Her life had all the trappings of a great Lifetime movie event. At the decidedly old-maidish age of 30, she married Thomas Anthony Trollope, a man who by all accounts was rather difficult to live with. The union produced six children over an eight-year period. Fanny, however, grew bored with her life, and upon the advice of her radical friend Frances Wright, she traveled to Nashoba, Tennessee to live in a commune with three of her children and their tutor Auguste Hervieu (he would later provide illustrations for many of her works). Adverse to “roughing it,” Fanny and her entourage quickly left the commune to set up an entertainment business in Cincinnati, devising spectacles such as the mock-Oracle “Invisible Girl” and a wax work show based on Dante’s Inferno. Alas, other business ventures proved faulty, and she went bankrupt. Unable to produce fare for the voyage back to England, Fanny toured America and gathered material for what would become the Domestic Manners of Americans.

Domestic Manners proved to be a success, and at the sprightly age of 53, Fanny could financially support her family through her writing. Critics and readers alike enjoyed her travel-writing style, which included commentary on the position of women and the inclusion of colorful incidents which were handled with a novelistic flair, along with the standard descriptions of the environment. She wrote other travel books, including Belgium and Western Germany in 1833 and Paris and the Parisians in 1835, all of which met varying degrees of critical success. In addition to her works on travel, Trollope also wrote several books dealing with social concerns of the day. Like her contemporary Charles Dickens, she was appalled by the conditions of child labor and wrote the novel The Life and Adventures of Michael Armstrong Factory Boy (1839). As an interesting side note, Dickens did not relish having a female literary competitor. In a letter to Edward Fitzgerald, he wrote of Fanny, “I will express no further opinion of Mrs. Trollope, than that I think Mr. Trollope must have been an old dog and chosen his wife from the same species.” Fanny also wrote an anti-slavery novel, The Life and Adventures of Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw (1836), which Special Collections recently acquired. The novel precedes both Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and William Wells Brown’s Clotel (1853) by nearly two decades. The mere fact that a woman decided to address and write about controversial social topics did not go unnoticed or uncriticized. William Makepeace Thackeray bemoaned the fact that Fanny Trollope dared to write about religious controversies. When reviewing her satiric novel The Vicar of Wrexhill (1838), he reprimanded her daring spirit and noted that her time would have been better spent “at home, pudding-making or stocking-mending, than have meddled with matters which she understands so ill.” Fanny, however, declined Thackeray’s advice and continued to avoid pudding-making and stocking-mending. Between 1832 and 1856, Trollope wrote 35 novels and 6 travelogues. Though she retired from writing in 1856, her sons Anthony and Tom both took up the pen. Anthony, of course, became famous for his novels, and Tom for his travel writing. Special Collections also has the outstanding Jacques and Suzanne Schlenger Collection of Anthony Trollope’s work. Stop by Special Collections, and perhaps see how Fanny Trollope’s novels inspired the output of her more famous son!

It is a pity that many do not know of the existence of Fanny Trollope, such an interesting woman, and now of course, most of her books are out of print, but it would be nice if some of the better ones could be reprinted, if only to give an insight into the domestic and political aspect of the time she lived. She was an amazing woman, with tremendous energy.