My time at Hopkins so far has been built off discovery. Discovering what it’s like to live in the States, discovering my ideal study places around the campus and the best food places in Charles Village, and discovering old and rare books at the Special Collections.

Alongside my intended major of Molecular and Cellular Biology, and my intended minor in Classics, I nevertheless still try to keep up with my other interests – the most prominent of which has been folklore. Over my time here, I acquired a few books on Irish folklore, a decent edition of Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, and have been continuing to make my way through all of Andrew Lang’s coloured Fairy Books. And of course, I’ve been exploring the works at the Special Collections.

STEM and the humanities are far too often viewed as opposing fields, but I like to think that this is not the case. The two have a lot more in common that many would imagine. Both require a generous degree of creativity, logic and reason to seek out the answer to some of life’s greatest questions, particularly those concerning the natural world. The methods used and the fields of interests investigated will differ, but both still serve the purpose of exploration and explanation.

STEM and the humanities are far too often viewed as opposing fields, but I like to think that this is not the case. The two have a lot more in common that many would imagine. Both require a generous degree of creativity, logic and reason to seek out the answer to some of life’s greatest questions, particularly those concerning the natural world. The methods used and the fields of interests investigated will differ, but both still serve the purpose of exploration and explanation.

This is where folklore and legend come in.

FOLKLORE has often been used as a means to seek an explanation for phenomena before such were elucidated with the scientific process (it has been proposed that the changeling myths were representative of children with development disorders), or to aid people with grappling with struggles and issues present in their daily lives (for instance, the Evil Stepmother trope is seen as an expression of fear over lost inheritance). Much like how tragedy serves a cathartic purpose, one’s pain and confusion is alleviated through these stories.

I once said that entering the Special Collections was like entering the faerie realm – one taste of it, and I would stay here forever. Of course, this place is a lot more pleasant than any hostage situation, and if anything, becoming a Freshman Fellows is making me more connected to the human world. The opportunity to investigate through works centuries-old and to have that glimpse in the minds of those of the past definitely gives me a decent scope of where I stand in this world.

Here, at the Special Collections, I’ve decided to focus my research on something that speaks to a very primal human instinct – fear. Throughout European folklore, natural philosophy and science, monsters and monstrosities are common and present. If fairytale tropes are often influenced by human struggles, or serve as a way of understanding inexplicable phenomena – I wondered –, is that the same case with monsters?

Here, at the Special Collections, I’ve decided to focus my research on something that speaks to a very primal human instinct – fear. Throughout European folklore, natural philosophy and science, monsters and monstrosities are common and present. If fairytale tropes are often influenced by human struggles, or serve as a way of understanding inexplicable phenomena – I wondered –, is that the same case with monsters?

I began my journey by going through books of natural philosophy – the precursor to our modern natural sciences. Some of these books contained studies of monsters and grotesques, or of mythical creatures rumoured to roam undiscovered parts of the world. Others are medical accounts, some containing foetal disorders or birth defects.

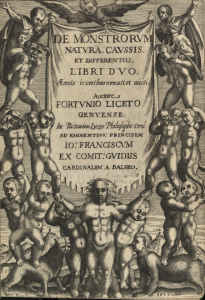

Of the former, one of these books was Fortunio Liceti (1577 – 1657)’s De monstrorum causis, natura et differentiis (“Of the Causes of Monsters, their nature and differences”), written as a documentation of reports of monsters and so-called “freaks” in nature during his time. What was particularly interesting was that Licetus did not emphasise the abnormalities of the creatures he wrote of. Rather, his view, which differed greatly from common European opinion, was that grotesques were fantastical rarities, comparable to an artist’s unconventional creation.

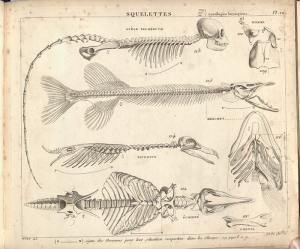

There was also a book written in French, with several anatomical drawings. It is surprisingly easy to mistake some of these illustrations for monsters or mythical creatures. In fact, with a human-like skull and ribcage, and the bones of a prehensile tail, the skeleton of a white-bellied spider monkey could also be passed off as a mermaid.

It was also interesting – as well as tragic and unfortunate – to note that people of ethnic groups outside of mainland Europe were included alongside collections of monsters. Bulwer’s Anthropometamorphis (Man Transformed, or the Artificial Changeling) contains a “pedigree of man”, culminating in the “English gallant”. Giovanni Botero’s Aggivnta Alla Qvarta Parte Dell’Indie contains some creatures we would regard as fantastical near the beginning, yet the last few pages are dedicated to foreign humans. These examples show a clear example of the degree of racism acceptable in the society under which the books were published then, and illuminates further ideas of the authors’ interpretations of “monsters”.

Throughout the books containing collections of monsters and grotesques, I observed a few common themes. For starters, many of these monsters and grotesques present were fusions of humans and animals. “Abnormal” numbers in body parts (such as multiple limbs or eyes), or body parts in different places (wings attached near the buttocks, arms at one’s neck and hip) were common. Additionally, there were many illustrations of conjoined twins and other birth defects. Although not as common, there were also quite a few instances of sagging breasts.

These have strong roots with reality. There’s nothing particularly alien introduced about the monstrosities present; all the “parts” present on them are things we can find in the real world.

I’m inclined to agree with Licetus. The sublime, perhaps confusing, beauty of nature is present in all its ugliness. These monsters are not grotesque because they are otherworldly. On the contrary, they are grotesque because they are normality altered – out of place with what we regard as conventionally beautiful.

This merging of natural philosophy, medical anomalies and folklore, I believe, provide an interesting insight on how we, collectively, as humans, mould and play around with the concept of “monster”. Just as fairytales take inspiration from the life experience of its storytellers, those who record and create monsters are shown to find their basis from somewhere.

As a Molecular and Cellular Biology Major, there is nothing more beautiful to me than life itself – and, in particular, the diversity of life. The world may not be filled with the same peculiarities in the tomes present at the Special Collection, but nevertheless, the variety of it is still to be appreciated.

So, I suppose, while I’ll be hunting monsters here at the Special Collections, what I really am finding is my own humanity.

Keyi Lin, Class of 2021