Preserved in Print, the current exhibition at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, examines eminent figures of African descent–political leaders, journalists, poets, actors, scientists, and thinkers–as they were represented through printed words and images in their own time and by later generations. Curated by seven graduate students in last year’s Black Print Culture course taught by Professor Nadia Nurhussein, Department of English, Krieger School of Arts & Sciences, the books, pamphlets, posters, portraits, and periodicals on display come from the Sheridan Libraries’ special collections holdings in Black history and culture, a growing area of rare materials. This interview with curator Susan Rivera, who contributed to the “Remembering Black Icons” section of the exhibition, illuminates the curatorial process and the connection between exhibitions and other forms of scholarship.

The exhibition has been extended through February in honor of Black History Month. Please pick up a free copy of the exhibition booklet!

What influenced your choice of exhibition materials? How do the materials you chose tie into your research interests?

· I saw Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War paintings a few years ago, his reworking of equestrian portraits by [17th-century Spanish painter Diego] Velasquez and [Neoclassical French painter] Jacques-Louis David. What stayed with me about Wiley’s project was its foregrounding of how the originals co-signed or arrogated power to their subjects. When our class was looking at J.A. Rogers’ “Your History” columns for [the weekly African American newspaper] the Pittsburgh Courier, I discerned a through-line between the state-sponsored propaganda of say, Napoleon I, and the insurgent work of visual culture.

· I’m interested in the question of how cities shape personhood and how a city is represented in literature and film. The New York of the Ghostbusters is very different from the New York of Teju Cole’s émigrés, Edith Wharton’s endogamous (and vicious) socialites, and N.K. Jemisin, and yet they are, technically speaking, about the same social ecosystem. How we perceive a city like New York, Toronto, or Baltimore is very much a product of the surrounding mythos of place that visual and print culture participate in.

Was there anything surprising about the materials you chose that you learned from examining original textual artifacts?

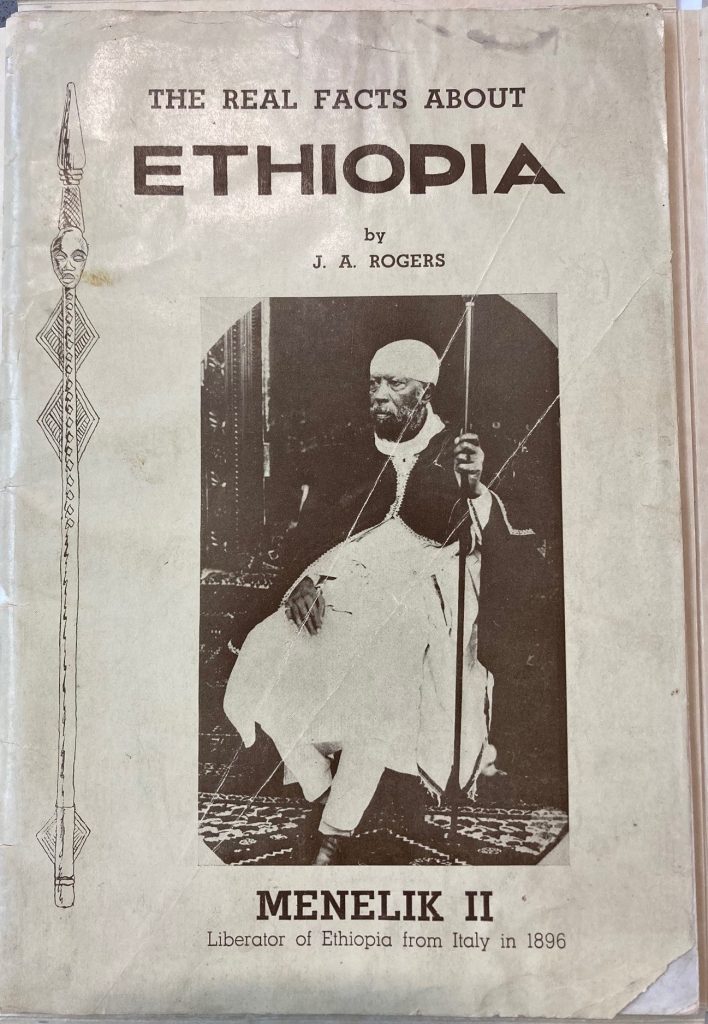

· I was surprised by the encyclopedic sweep of topics covered in both short pamphlets like The Real Facts About Ethiopia and a “coffee table” volume like Africa’s Gift to America. Uplift is a hackneyed word, but you do sense in Roger’s oeuvre a commitment to exalting black life and that he understood the constitutive power of a story. In the foreword to Nature Knows No Colorline, he muses about the taxonomic origins of race, tracing it back to Hyginus’ Fabulae and the story of Phaeton, who accidentally “burnt” the skin of “Aethiops.” This would have been decades before Sylvia Wynter’s essay, “1492: A New World View,” considered the question of how race was a manufactured category of personhood.

How was assembling a group of objects for an exhibition and writing exhibition texts similar to and/or different from more familiar research and writing practices?

· I’ve always found museum title cards and labels extraordinarily well written. There’s a funambulist’s line you walk between erudition, conciseness, and legibility when you’re writing for an exhibit. I don’t like the idea of a “general” audience—there’s no such thing. You are writing, always, for people, and I like that it’s a pedagogical exercise in conveying information that you think is important.