[Today’s post is written by a classmate of mine, Dr. Patricia Maurice. A 1982 graduate of Hopkins, Patricia is a professor emerita in the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Earth Sciences at the University of Notre Dame.]

One of the benefits of being a Hopkins Earth and Planetary Sciences graduate (’82) is the ability to travel anywhere and always see the world with a bit of an expert’s eyes. Every time I enter a city, for example, I look for where they get their water, what stones are used in construction, and how the geology and geography have sculpted the city’s outlines and shaped the economy.

In April 2023, when my husband and I visited Civil War battlefields at Shiloh, Tennessee, and Corinth, Mississippi, I was looking to understand how the landscape, including the presence and absence of water resources, affected the battles. I could never have foreseen how the trip would reinforce my appreciation for the long and storied legacy of Earth Sciences at my alma mater.

A rainy afternoon seemed like a good time for a side trip to the Tennessee River Museum in Savannah TN. Upon entering the small but excellent museum, my eye was drawn to a captivating exhibit about local geologist hero (Robert) Bruce Wade (1889-1973). That name rang a bell from my undergraduate years. Sure enough, Dr. Wade had graduated with a PhD from Hopkins!

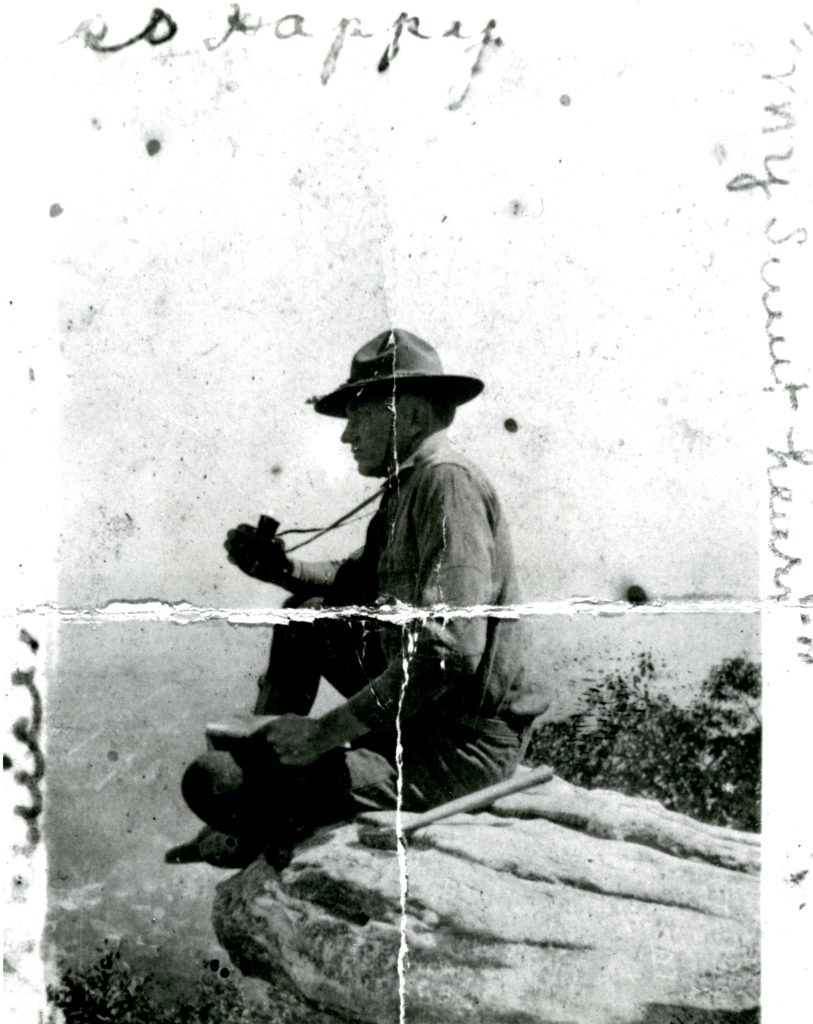

[Image at left: Candid photograph of Bruce Wade sitting on a rock holding binoculars, c. 1914-1917, Johns Hopkins University Graphic and Pictorial Collection]

According to the museum’s exhibits, “Bruce Wade pioneered the in-depth study of the fossil deposits of Middle and West Tennessee. Described by his peers as gifted and energetic, Wade discovered the world-famous Coon Creek fossil formation during the summer of 1915. While new species discoveries are normally limited to 10-15 per lifetime, Wade discovered over 180 at the Coon Creek site” (Quote from displays in the Tennessee River Museum, April 2023). Note to readers: the discovery of even one new fossil species is considered a big deal in paleontology.

The exhibits went on to describe how during his 1914-17 doctoral studies, Wade collected the first fossil insect preserved in amber in North America. I’m sure every school trip to the museum emphasizes this connection to the popular Jurassic Park movies. The accompanying exhibits included everything from his trusty field hammer and hand lens (I still have mine from my undergrad days!) to a field notebook to that famous insect in amber.

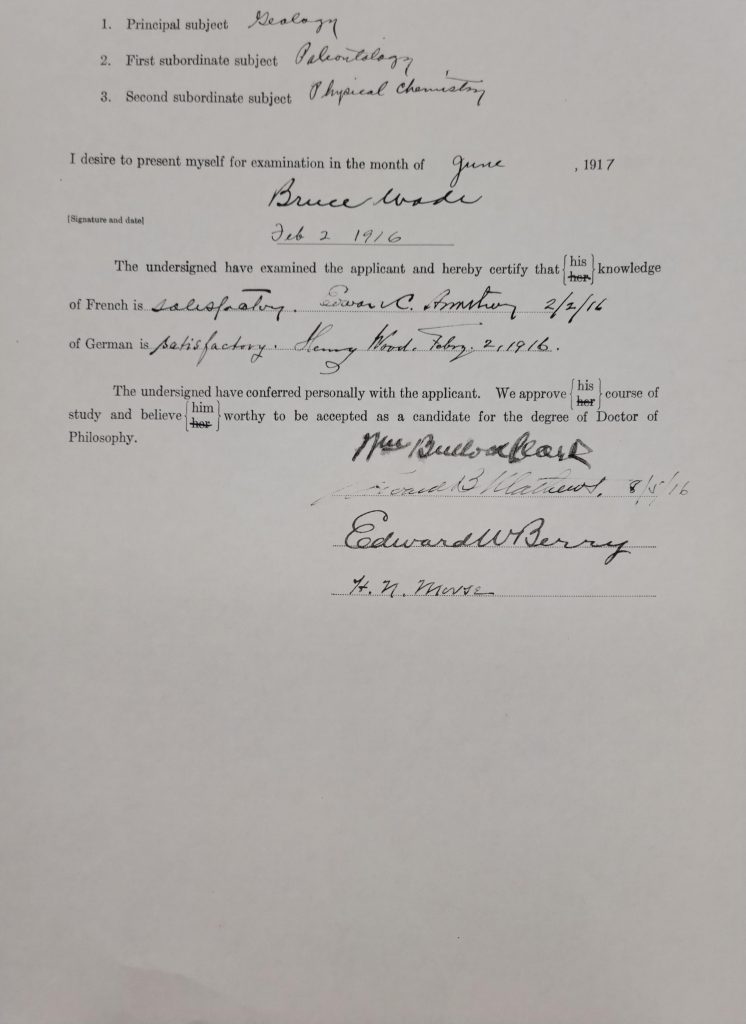

When I returned home, Margaret Burri, a Hopkins classmate at the Sheridan Libraries, helped me discover more about Bruce Wade. His graduate advisor at Hopkins was the eminent paleobotanist Edward W. Berry. He also worked in the lab of William Bullock Clarke, a stratigrapher of the Atlantic Coastal Plain whose work I relied on as a young U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist. Like so many men of his generation, Wade served in World War I. He went on to work as an oil and exploration geologist but his career was cut short by a debilitating illness (Brister, R.C., 1994, Bruce Wade: Tennessee’s forgotten geologist, Earth Sciences History, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 47-51.)

The fossils at the Tennessee River Museum reminded me of the years I spent studying at Hopkins: the summer-long field trip to Wyoming with paleontologist Bob Bakker (who helped develop the warm-blooded dinosaur theory and whose doppelganger was devoured by a T. Rex in one of the Spielberg movies); the joy of working in the human paleontology labs of Alan Walker and Pat Shipman; the many challenging geology and paleontology courses taught by faculty like George Fisher, Lawrie Hardie, and Steve Stanley; the field trips to Camp Singewald.

[Image right: Wade’s application for graduate studies, Special Collections, Sheridan Libraries]

Although I chose to pursue a career in environmental geology and engineering, often slogging through wetlands or immersed in the lab, I will always have a special place in my heart for the rock-hammer-toting field geologist. I was thrilled to see Dr. Bruce Wade remembered by his local community decades after his passing. My husband likes to say that every town has its story. The story of Savannah, Tennessee and the Tennessee River isn’t just about major historical events like the Trail of Tears and the Civil War. It’s also about how Hopkins’ Ph.D. Bruce Wade put the local area on the map forever for its fossil treasures. [Author Patricia A. Maurice as a young Hopkins geologist excavating fossils in Wyoming,1980.]