Fireworks have been around since the Han Dynasty in China (200 B.C.E.), when hollow bamboo sticks were thrown into fires to expand and eventually explode. Chemicals were soon added to create colorful effects, and fireworks made their way to Europe via the Silk Road. In addition to dozens of songs celebrating Independence Day in the United States, the Levy Sheet Music Collection also has a few lithograph covers with other references to fireworks.

“Musical Rockets” was published in New York, 1853. The cover shows a gigantic firework show over a lavish estate, with onlookers watching from numerous balconies. The cover achieves quite a depth of color despite only using green, orange, white, black, and a bit of yellow. However, the show could almost be mistaken for a volcanic eruption based on the apparent fireball close to the ground. The music is intended to capture the sounds of a firework—the very beginning has a series of very high notes on the piano followed by cascading scales to mimic an the explosion and subsequent falling of a firework:

The rest of the song is not for the faint of heart—most of it would take a very skilled pianist to pull off:

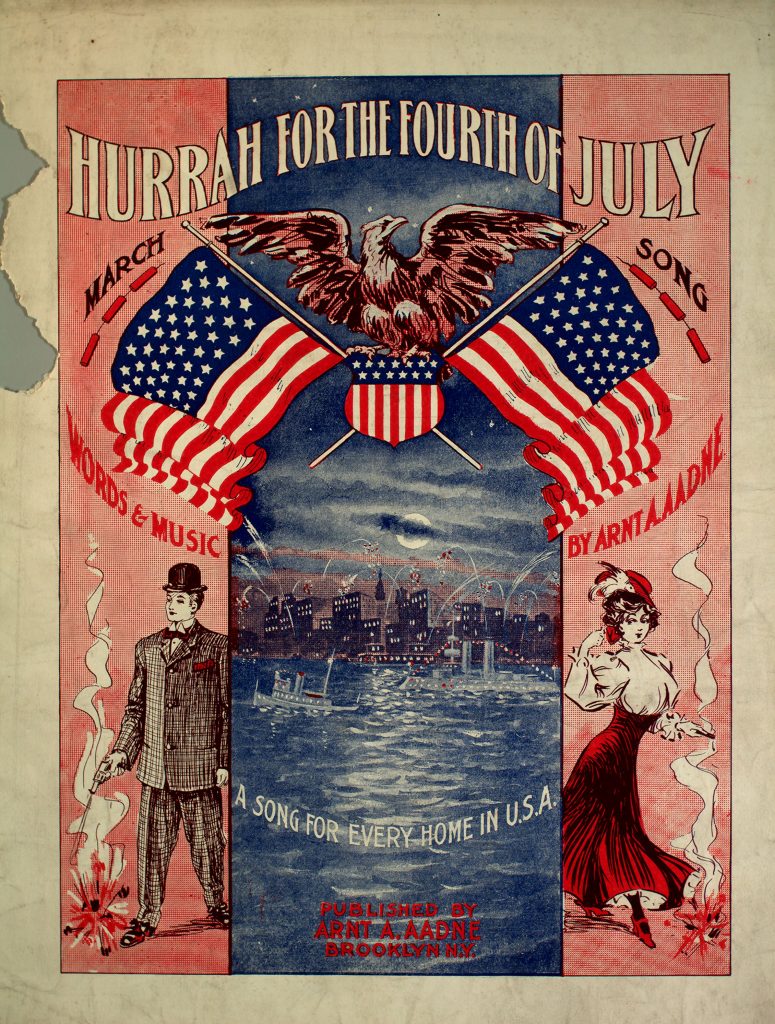

“Hurrah for the Fourth of July” has a lot packed into the cover. There are firecrackers under the words “March” and “Song,” and a whimsical firework scene over New York City. The song was published in Brooklyn in 1905, so the perspective of the cityscape seems to be from that side of the river.

I have many questions about the two figures on the cover—why is the person on the left with the impossibly shaped suit holding a firework gun, shooting directly at his (or possibly her) feet? The woman on the right is at least covering one of her ears, but why is she stepping forward into the firework? It’s not surprising that most emergency rooms see a boom in firework-related injuries on July 4.

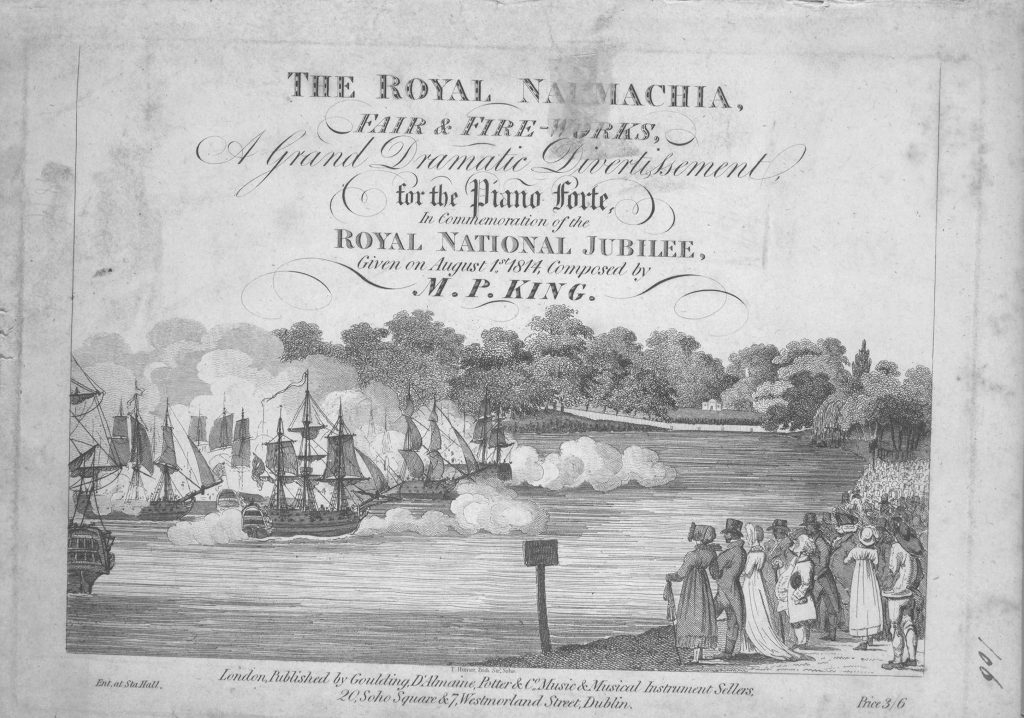

“The Royal Nalmachia” was written after the 1814 Royal National Jubilee in London, a festival celebrating the Treaty of Paris and featuring artillery and fireworks. This cover only appears to show cannon fire, but the rest of the festival had more fireworks spread over three parks– unfortunately, the jubilee ended with a pagoda catching fire and burning down.

This week’s final song isn’t strictly related to fireworks, but is instead a hilariously bad English reaction to the American Revolution. “The Good Subjects of Old England” was published in London, 1779. The first verse sounds like the singer is being punished by writing lines on a chalkboard: “We must be good subjects, we must be good subjects, we must be good subjects, when our hearts are thus warm’d, we must be good subjects.” The chorus follows: “Here’s a Health to Old England the King and the Church, may all plotting Contrivers be left in the Lurch. May England’s GREAT MONARCH bravely fight his just Cause, Establish long PEACE, our RELIGION, and LAWS.”

Happy Independence Day!

As the curator of the Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection, a phrase I hear often is “I didn’t know sheet music could be used to study…”

Levy collected 30,000 songs over 50+ years not to perform, but to use as a lens for studying history. To make this easier, Levy organized his collection by subject, rather than title or composer. As a result, there are hundreds of unique subjects that can be used to filter the collection. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to dive into some of the more fascinating, obscure, and strange subject headings in the collection. Each week, I’ll focus on a different subject — stay tuned for more deep dives! You can view the entire digitized collection here.