Enjoy this post by DJ Quezada, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2020-2021 academic year!

A lot has transpired since my most recent entry. When I last posted, it was November of 2020, and I was working with Special Collections to do my research from Bentonville, Arkansas– over a thousand miles away from the Special Collections facilities on the Homewood campus. In January, however, the opportunity arose to finally live on campus for the first time, and thus I could finally experience the maps and resources I had looked at for so long on a computer screen firsthand.

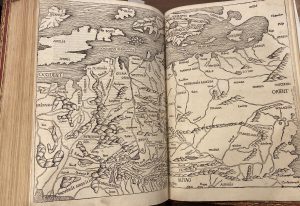

The first day I was able to step into the Special Collections reading room and peruse the works I had selected carried with it a feeling akin to Christmas. The first piece I had the chance to view was the , a world history book published in 1493. As a frequent reader of history, it absolutely fascinated me to see a book of European history that didn’t include the Protestant Reformation — because it would not begin to take place until over 25 years after the book’s publication! Equally fascinating to me were the inset drawings of cities like Damascus decorated with architecture typical of Northern Europe– because the author had never visited so see that the buildings in Damascus did not resemble his native Nuremberg in the slightest!

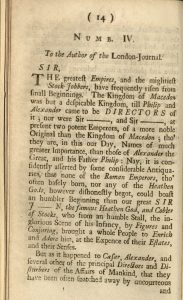

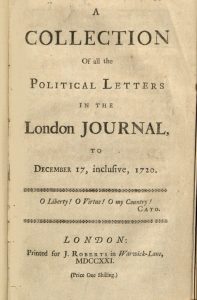

As the semester wore on, my project began to have a clearer focus as well. During the fall semester I had taken particular interest in the events surrounding the British South Seas Company– a failed colonial venture whose crash created one of capitalist Europe’s first major economic crises. Particularly important to me in this instance is the company’s use of highly respected mapmakers such as Hermann Moll (as seen in my previous blog post) to produce maps promoting the colonial venture. Since the vast majority of Europeans had little direct interface with the Americas outside of maps, these well-produced maps served as excellent cover for a business venture that was doomed to fail. I felt like this was a perfect rendition of the project’s original theme: exploring how maps tell stories–especially when these stories aren’t the most factual. Throughout my research, I also came across selections of political journals and news publications from 18th century London– narrating in real time the demise of investors who had likely been duped by the maps published alongside the South Seas Company’s solicitations for investment. Some of my favorites come from A Collection of all the Political Letters in the London Journal.

As the semester wore on, my project began to have a clearer focus as well. During the fall semester I had taken particular interest in the events surrounding the British South Seas Company– a failed colonial venture whose crash created one of capitalist Europe’s first major economic crises. Particularly important to me in this instance is the company’s use of highly respected mapmakers such as Hermann Moll (as seen in my previous blog post) to produce maps promoting the colonial venture. Since the vast majority of Europeans had little direct interface with the Americas outside of maps, these well-produced maps served as excellent cover for a business venture that was doomed to fail. I felt like this was a perfect rendition of the project’s original theme: exploring how maps tell stories–especially when these stories aren’t the most factual. Throughout my research, I also came across selections of political journals and news publications from 18th century London– narrating in real time the demise of investors who had likely been duped by the maps published alongside the South Seas Company’s solicitations for investment. Some of my favorites come from A Collection of all the Political Letters in the London Journal.

As always, this project could not have been completed without the incredibly helpful guidance of Amy Kimball throughout the year. In all of our meetings, Amy was influential in helping me turn my passion for maps and cartography into a well-developed final product for the freshman fellows program. To that I owe her immense thanks.