Enjoy this post by Kobi Khong, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2020-2021 academic year!

Welcome one and welcome all, whether you be readers or eaters, librarians or pescatarians, academics or snack-ademics, I hope you’ll enjoy the cornucopia of knowledge that I’ve prepared for you today and leave with a belly full of information!

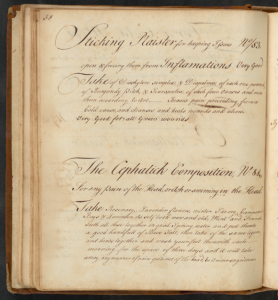

For a short introduction, my name is Kobi Khong, and I am from Southern California and serving the student body as the Freshman Class President, but more importantly–I am here to serve you as your Cookbook Connoisseur to give you a glimpse into the “Cooks & Their Books”–my research project with the Special Collections department at Hopkins! Now if you’re only two sentences into this blog post and your head is already pounding at these awful puns then worry not my friend, perhaps I could direct you towards “pharmacy receipt” N° 84 in J Tompkin’s 1766 manuscript recipe book, a recipe for “The Cephalick Composition: For any pain of the Head or Ach or swiming in the Head.”

Now, whether washing your feet in “bays of lavender its self both new and old” can cure your maladies is up for debate, but what is interesting is the intersection of these foods/home remedies and our culture; seeing why people ate what they ate, cooked what they cooked, and how it was influenced by the culture of the era (or even vice versa, how it influenced the culture at that time), is a glimpse into a point in history where time revolved around food, well, now that’s food for thought.

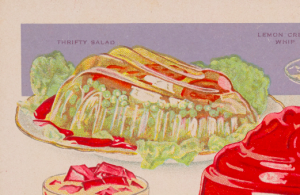

For everything from a recipe on how to make Calf’s Foot Jelly from an 18th century manuscript to a 20th century Jell-O recipe book with wonderful recipes like a “Thrifty Salad” filled with “alternate layers of salmon, cold cooked peas and cold Jell-O,” and more mustard than one could muster, there is an inherent part of human nature which makes us story tellers and one of the best ways that we’ve passed down our customs and traditions across generations is through food.

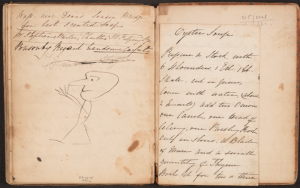

Cooking is one of the most personal things that people can do and sharing those memories and meals with people that you love is one of the methods we show that we care. As a result of that, cookbooks are more than a list of instructions, and throughout my research that shows in the weathered pages that have lasted centuries. It allows us to look back into that moment in time of the life of the author and experience what they might have been going through at the time. One of my favorite examples of such is from a recipe book from 1840; adjacent to a recipe for Oyster Soup and other scribbled out recipes is a little drawing of a person with their arms up walking across the page. These types of stray doodles are a delight and not just because they’re a break from deciphering 19th century cursive handwriting, but also because it emphasizes the human aspect of cooking. Although it’s easy to see these authors from the past as just history, it’s delightful to see that even in the 1800s someone took the time out of their day to draw a little sketch in a book that they assumed would just be passed down in their family, never imagining it would be preserved for nearly two centuries later to be studied.

Another component of cookbooks that is so fascinating, that I’ve been researching is their ability to capture historical changes on a larger scale, for example here I have five cake recipes found in cookbooks spanning 260 years.

Another component of cookbooks that is so fascinating, that I’ve been researching is their ability to capture historical changes on a larger scale, for example here I have five cake recipes found in cookbooks spanning 260 years.

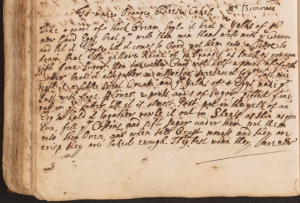

The first one being from ca 1690 is a bit tougher to read than most, one of the reasons for which could be contributed to the quality of ink used at the time. During that era iron gall was the most commonly used type of ink. The ink is very corrosive and over time can eat through the paper, making it difficult for preservation. Perhaps the recipe for an orange cheese cake is worth the effort of deciphering!

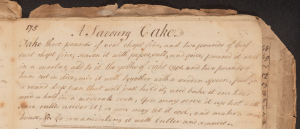

In the 1780 manuscript, you can see an increase of care taken in inscribing recipes and the slightly worn pages and the numbering of the recipe for “A Savory Cake” shows a nice history of its practical usage. Something that you may notice is missing from what we usually think of when we see a recipe is a list of ingredients which hadn’t yet become a norm.

In the 1780 manuscript, you can see an increase of care taken in inscribing recipes and the slightly worn pages and the numbering of the recipe for “A Savory Cake” shows a nice history of its practical usage. Something that you may notice is missing from what we usually think of when we see a recipe is a list of ingredients which hadn’t yet become a norm.

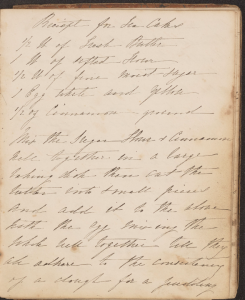

Our 1840 recipe for cake (although with terrible handwriting), is the first time that we see in our manuscript books the explicit listing of the ingredients required to bake the cake (which by the way only requires 5 ingredients), so feel free to let us know how it tastes if you have the stomach of a 1840s gold rush miner! The recipe was compiled by an Englishwoman named Ellen Bankes, and she started to record her recipes on February 14, 1840! She also drew the doodle of the little man that we discussed earlier.

Our 1840 recipe for cake (although with terrible handwriting), is the first time that we see in our manuscript books the explicit listing of the ingredients required to bake the cake (which by the way only requires 5 ingredients), so feel free to let us know how it tastes if you have the stomach of a 1840s gold rush miner! The recipe was compiled by an Englishwoman named Ellen Bankes, and she started to record her recipes on February 14, 1840! She also drew the doodle of the little man that we discussed earlier.

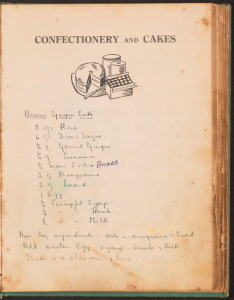

One of our 20th century cookery manuscripts is especially interesting since it is the first in our collection to dab into the commercialization of cookbook notebooks. F.J. Ward, a publishing company in London, manufactured “A Cookery Notebook,” blank pages with sections of cuisine for people at home to fill out with their own recipes. The printed subtitle and illustration are a reflection of the increasingly industrial world, as technology being developed began showing up within cookbooks as well! Our copy features recipes by a woman from Southampton, England named Margery Pope. The recipes span 1938 through 1947.

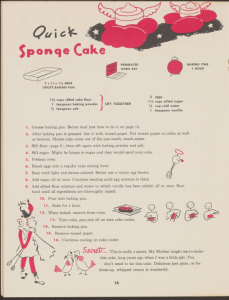

The last cookbook I have for you today is a more recognizable compendium that you might have lying around the house. Sugar An’ Spice and All Things Nice is a fully printed cookbook sold to consumers with adorable illustrations alongside recipes for food commonly eaten during the time as well as cooking tips for the traditional nuclear family.

As you can see there’s quite a bit more to cooks and their books that –meats- the eye, and this past semester of research has been one of the most interesting things that I’ve ever done. I’ve only whetted my appetite for what’s more to come and I’ll hope you’ll join me back in the spring for a second helping, until then I bid you adieu!