Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of texts from the 1820s through the 1930s—speeches, private writings, and published poetry, fiction, and journalism—by North American women who brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our series title, please see the first post. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post is by Lara Uthman, an English and Writing Seminars major in the class of 2021.

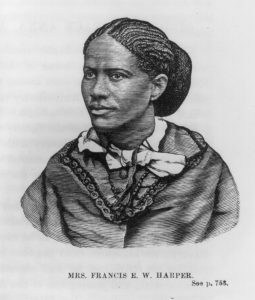

Portrait of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, from William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872). This image from the Library of Congress via Wikimedia.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper posited her own interpretation of the Bible as a means of achieving freedom for African American people.

During the era of human chattel enslavement and afterwards, many African American people looked to religion for guidance. The creation of independent African American churches where biblical studies served as a gateway to other kinds of learning made religion a topic of intellectual curiosity as well as a source of spiritual counsel. Renowned poet and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) exemplified this phenomenon. Born in Baltimore, the city with the largest free Black population in the United States before the Civil War, Harper attended the Watkins Academy, run by her uncle and minister at the Sharp Street United Methodist Church, where she received a strong foundation in biblical studies, amongst other subjects. This connection between her secular education and religious training is prevalent in much of her work, particularly her collection of poems entitled Forest Leaves.

Forest Leaves begins with a preface, where Harper discusses the horrors of slavery and one significant thing that it stripped away from enslaved people—opportunities for learning and thinking. She writes:

As a body, their [African Americans’] means of education are extremely limited; they are oppressed on every hand; they are confined to performance of the most menial acts; consequently, it is not surprising that their intellectual, moral and social advancement is not more rapid. Nay, it is surprising, in view of the injustice meted out to them, that they have done so well. Many bright examples of intelligence, talent, genius, and piety might be cited among their ranks, and these are constantly multiplying (Harper, 4).

Here, Harper makes the important point that, despite the systematic attempt to squash their talents, African American people still excel in intellectual pursuits—brilliantly flipping the tragic slave narratives of the time. This acknowledgment of pain tied in with the recognition of success sets the tone of Harper’s entire collection of poems: despite all else, her people prevail. This sentiment is evident in many of the poems in this collection, but particularly “Ethiopia” and “Bible Defence of Slavery.”

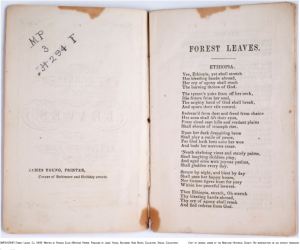

“Ethiopia” in Forest Leaves by Frances Ellen (Watkins) Harper, ca. 1849. Published by James Young, Printer, corner of Baltimore and Holliday Streets, Baltimore. 3.50 x 5.5 inches. Maryland Historical Society, MP3.H294F, Rare Books Collection, Special Collections.

The first poem in Forest Leaves is titled “Ethiopia.” The first stanza, “Yes, Ethiopia, yet shall stretch / Her bleeding hands abroad, / Her cry of agony shall reach / The burning throne of God” (1-4) comes from the Bible, specifically Psalms 68:31, which states, “Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God.” This statement resonated with many African American people during the time and was often preached at meetings of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (Shilliam). The image of Ethiopia, one of the only African countries to resist colonial rule, stretching out to God was a statement of hope for all members of the African diaspora—that they would one day break away from colonial rule and that their cries of oppression would be heard by God. The poem continues on this message throughout, including imagery of being freed from chains and finally experiencing peace. These images alone exhibit Harper’s extensive knowledge of scripture, but it is also interesting to note the style of the poem in general. Her words are reminiscent of a sermon, as evident by the first line that signals back to what preceded it. She writes, “yes, Ethiopia,” as if clarifying something she said before. The sermon was a genre in which African American preachers demonstrated intellectual prowess, not just spirituality. So, in invoking the sermon, she is invoking that intellectual tradition and her rhyme scheme, meter, and other formal attributes of this poem demonstrate her mastery of these poetic conventions. The sermon-like style in which she wrote compounds the hopeful tone that Harper invokes throughout the poem, and it is clear that she is utilizing this religious tradition to express a message of hope for her people.

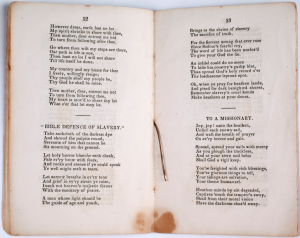

“Bible Defence of Slavery” in Forest Leaves by Frances Ellen (Watkins) Harper, ca. 1849. Published by James Young, Printer, corner of Baltimore and Holliday Streets, Baltimore. 3.50 x 5.5 inches. Maryland Historical Society, MP3.H294F, Rare Books Collection, Special Collections.

Harper employs religion in many different ways throughout her collection of poems, and one can contrast her use of religion in “Ethiopia” to her slightly different use in “Bible Defence of Slavery.” This poem’s title refers to an essay with the same title by a pastor named Josiah Priest, which used the language of the Bible to rationalize slavery. By re-purposing the essay’s title and responding to the claims Priest makes, Harper exposes the morally reprehensible claims he makes in his essay. The fourth stanza of the poem, “A man whose light should be / The guide of age and youth, / Brings to the shrine of slavery / The sacrifice of truth” (16-20), asserts that, because he is a preacher, it is especially shameful for Priest to promote the idea that the Bible defends slavery—not simply because it is untrue, but because it is morally wrong according to the principles of his religion. As a man whose light should guide the youth, it is unjust for him to be untruthful about the Bible’s stance on slavery, according to Harper. In this poem, Harper takes a more vehement stance against slavery and uses the guiding principles of religion to do so, unlike in “Ethiopia,” in which she has a more hopeful tone and aims to inspire her people. She is also proclaiming her intellectual ability by combating old narratives and advocating for her people. In both poems, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper argues forcefully for the freedom and advancement of her people, but she does so through one of the most influential avenues of the time: religion.

Works Consulted

“Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.” Archives of Women’s Political Communication, University of Iowa. awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/directory/frances-ellen-watkins-harper/.

Foner, Eric, and Olivia Mahoney. “Building the Black Community: The Church.” America’s Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/section2/section2_church.html.

Ortner, Johanna. “Lost No More: Recovering Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s* Forest Leaves.” Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life 15.4 (Summer 2015). commonplace.online/article/lost-no-more-recovering-frances-ellen-watkins-harpers-forest-leaves/.

Shilliam, Robbie. “A Global Story of Psalms 68:31.” Robbie Shilliam, November 7, 2012. robbieshilliam.wordpress.com/2012/11/07/a-global-story-of-psalms-6831/

Sinha, Manisha, et al. “The Other Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.” Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life 16.2 (Winter 2016). commonplace.online/article/the-other-frances-ellen-watkins-harper/.