“America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash,” a frustrated Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote to his publisher in 1855. With ironic reference to his term, this blog series focuses on North American women who, from the 1820s through the 1930s, brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities in their speeches, private writings, and published poetry, fiction, and journalism. As we in the United States observe the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment and celebrate all those who fought for suffrage, “Scribbling Women” aims to recognize women who grappled in their texts with questions of freedom, justice, and rights—before, during, and after the concerted political effort to win the vote for women.

Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of the texts under consideration. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post is by Nandan Kulkarni, a molecular and cellular biology major in the class of 2022.

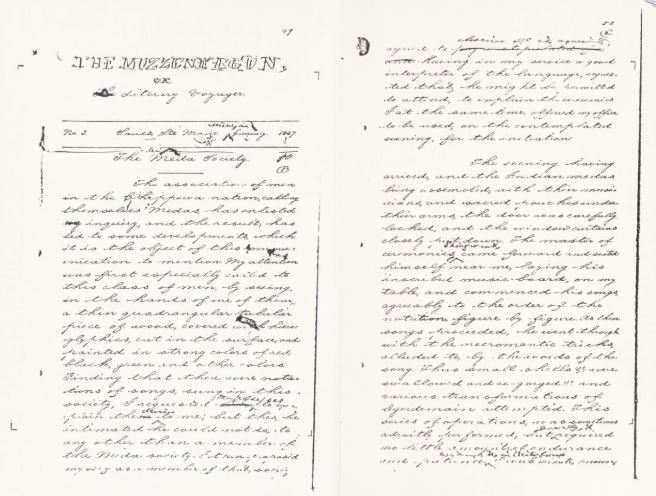

Facsimile of pages from the manuscript magazine The Muzzeniegun, or, Literary Voyager, by Jane and Henry Schoolcraft. Reprint edited by Phillip Mason. Michigan State University Press, 1962, via HathiTrust.

According to poet Jane Schoolcraft, the name “Bame-wa-wa-ge-zhika-quay” can be translated to “Woman of the Sound that the stars make Rushing through the Sky.” This was the name given to Schoolcraft in 1800 when she was born to the Anishinabe (Ojibwe) woman Ozha-guscoday-way-quay (Green Prairie Woman) and the Scottish-Irish fur trader John Johnston. As a result of her parentage, Schoolcraft was exposed to both Ojibwe and European traditions, stories, and histories. This meeting of cultures shows itself in many of Schoolcraft’s writings, though little of what remains directly confronts settler colonialism. Much of Schoolcraft’s work may have been lost altogether. As far as most scholars know, Schoolcraft never published printed books of her writing. Her largest audience came from readers of The Muzzeniegun, or, Literary Voyager, a handwritten literary magazine she co-edited and co-published in the mid 1820s with her husband Henry Schoolcraft, who was involved in governmental work on “Indian affairs.” (See here for reprints of Muzzeniegun.) According to the Philip Mason, in his introduction to a transcript of the Muzzeniegun, only one copy was ever written for some issues of the magazine (Mason, xv).

The Muzzeniegun published several of Schoolcraft’s translations of Ojibwe stories, possibly with the aim of recording Native American culture for academic purposes. Schoolcraft also contributed original poems without using her full name, many of which expressed personal and individual ideas and emotions, such as the defamation of her grandfather, the warrior chief Waub Ojeeb, or her feelings about the death of her son Willy in his infancy. While Henry Schoolcraft was widely published as a geographer and anthropologist, Jane Schoolcraft’s work was often overlooked after her death in 1842. However, there has recently been a renaissance in the study of Schoolcraft, including her original work in English and the Ojibwe language. In her writing, there is an interplay between the expression of cultural heritage and original ideas that continues to shape the way modern readers and scholars approach her work.

Schoolcraft’s writing was not necessarily motivated by a need to address white readers. The Muzzeniegun was mainly distributed among family and friends, some of whom were white and others Ojibwe. Many of her poems are conventionally structured English poems that come across as personally motivated even when they engage Native American topics. To expect Schoolcraft’s writing to explicitly address discrimination, colonization, and the need to preserve indigenous culture may be unfair to the life she lived. Some of us may be projecting onto her our own ideas of what an early Native American author should be, but Schoolcraft’s poems can be appreciated on their own for what they are. Any form of Schoolcraft’s personal expression is tied together with Ojibwe representation, including her writing that follows a conventional English structure.

These connections are present in the poem “Invocation To My Maternal Grandfather On Hearing His Descent from Chippewa Ancestors Misrepresented,” where the speaker reassures Waub Ojeeb that his people will remember his nobility despite rumours that he was born to an enemy tribe. She calls to him beyond the grave, at first encouraging him to rise up and “wield again thy warlike spear!” and remind his people of his bravery and valor. Of course, no one can return from the dead, but in the course of the poem the narrator recounts the shining legacy of the chief. She juxtaposes his rising to battle in life, depicted “Like a star in the west” during sunset, powerful against the back of the Ojibwe and dazzling their enemies in front. The poem progresses across five stanzas to a conclusion where she reassures him, “Rest thou, noblest chief!”, that Schoolcraft, his “child’s child,” will always hold his memory close to her heart. The final stanza feels warm and tender with the narrator’s expression of love for her grandfather, after all the intensity and chaos of war and conspiracy. The title of the poem leaves no ambiguity as to the poem’s intention. Each stanza consists of a line in iambic pentameter or sextameter (a line consisting of five or six iambs respectively), followed by a rhyming couplet in iambic dimeter with a caesura (two rhyming lines in iambic dimeter broken by a pause), which changes the pace of the poem. The first couplet is followed by a line in iambic tetrameter which rhymes with the first line. Another pair of rhyming couplets follows. Each stanza concludes with two rhyming lines in iambic tetrameter. In this way, the metrically complex poem flows with some tension and drama, but every stanza concludes in a conventionally satisfying way.

The poem is filled with clever imagery and has an interesting rhythm, and I find it an example of Schoolcraft’s originality in expressing ideas to her personal community. Modern readers can find in it a small piece of history preserved through English poetry, depicting political dissent in the Ojibwe community in 1827. Our wonderful professor proposed that “perhaps this poem is asserting that tribal history is important in its own right, not just in relation to European affairs or even European oppression.” I agree, in particular, that to a modern reader this poem can assert the importance of history and comment on the European-centered nature of its study, while Jane Schoolcraft’s motivation at the time could have been to honor and defend her beloved grandfather. Schoolcraft’s work exemplifies the fact that an author’s work sees several lives, with meaning and purpose that change over time, along with its readers. For modern readers to fully appreciate Jane Schoolcraft—her work and her life—it is necessary to also consider how other readers did so.

Ironically, as I’ve said, Schoolcraft’s readership dropped away after her death, probably, at least in part, because it was hard to find copies of her manuscript publications. But there is light at the end of that tunnel! In researching Schoolcraft online, I found just as interesting as her work the modern community who collect and continue her legacy. A resurgence of interest in Schoolcraft’s writing has occurred in the twenty-first century, with searches for and rediscovery of unpublished manuscripts, letters, and anecdotes. I also found sheer enthusiasm in individual researchers like Timm Severud, Robert Dale Parker, Margaret Noodin, Maureen Konkle, and Christine Cavalier, who have studied Schoolcraft and provided most of the information I could find on her, and in communities like the Bay Mills Indian Community, which worked with the Chippewa County Historical Society to organize tours of signature places in Schoolcraft’s life.

The new conversation around Schoolcraft helps people like me gain knowledge which would have been nearly inaccessible just fifteen years ago, such as the original poetry she wrote in her Ojibwe language. As an English standard for writing Ojibwe words had not been established at her time, Schoolcraft exercised creativity in simply putting the poem into written form. These poems appear as free verse, with single compound words forming most lines. One such poem is called “On leaving my children John and Jane, in the Atlantic states, and preparing to return to the interior,” or its original title “Nininendam,” which is simply translated to “Thinking.” In it, she laments leaving her children in a boarding school (even if an elite boarding school) and returning to her home in Sault Sainte Marie. Thanks to Margaret Noodin, a recording of this poem put into song can be heard at Ojibwe.net, a site dedicated to the preservation of the Ojibwe language, Anishinaabemowin. Also, a free-verse translation of this poem by Robert Dale Parker can be found in The Sound the Stars Make. “Nininendam” also appeared in Henry Schoolcraft’s memoirs, published in the mid-1800s, where he translated it into rhyming couplets. But now, Jane Schoolcraft’s poem stands alongside the rest of her recovered work in its original form, with an accompanying translation meant specifically to preserve the Ojibwe poem in English. While Henry Schoolcraft’s modified version of the poem may accurately express some of its ideas, I see significance in how differently scholars treat her work today. Their efforts proceed with respect and a recognition that Schoolcraft’s writing can be original, personal, and a window into her community. Readers like me must remind themselves that we are here to appreciate the work of an individual who we cannot expect to completely understand. Schoolcraft did not set out to document her life the way her husband attempted to record Native American culture. While much will remain unknown about Schoolcraft, about her struggles, culture, ideas, and lost work, the parts which have been preserved offer historical and artistic enrichment over two hundred years later.

Works Consulted

Kilcup, Karen. “Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bame-wa-wa-ge-zhik-a-quay, Woman of the Stars Rushing Through the Sky; Ojibwe, 1800-1841).” Native American Women’s Writing c.1800-1924: An Anthology. Blackwell, 2000.

Konkle, Maureen. “Recovering Jane Schoolcraft’s Cultural Activism in the Nineteenth Century.” The Oxford Handbook of Indigenous American Literature. Edited by James H. Cox and Daniel Heath Justice. Oxford, 2014.

Mason, Philip P. “Introduction.” The Literary Voyager or Muzzeniegun. Jane and Henry Schoolcraft. Reprint. Michigan State University Press, 1962.

Noori, Margaret. “The Complex World of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft.” Michigan Quarterly Review, Volume XLVII, Issue 1, Winter 2008.

Parker, Robert Dale. “Myths.” The Sound the Stars Make website.

Ross, Donald, et al. “Voices From the Gaps: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft.” University of Minnesota, Fall 2004.

Schoolcraft, Jane. The Sound the Stars Make Rushing through the Sky: The Writings of Jane Johnstone Schoolcraft. Edited by Robert Dale Parker. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

—–. “Nininendam.” Sung by Margaret Noori. Ojibwe.net website.

Schoolcraft, Jane and Henry. The Literary Voyager or Muzzeniegun. Reprint. Michigan State University Press, 1962.

Severud, Timm. “Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Obahbahmwawageezhagoquay) Biography.” Canku Ota: An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America, Issue 85, April 13, 2003.

Sultzman, Lee, ed. “Ojibwe History.” Tolatsga.org website. June 21, 2000.