Today, we hear from Margo Peyton and Michael Healey about their experiences as Hugh Hawkins fellows! Funding provided by Hopkins Retrospective supported their research at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions from June to August 2019. Margo and Michael then presented at an event for DURA and Hugh Hawkins fellows to reveal and explore their findings with faculty, librarians, and fellow students in October 2019. Read on for their incredible insights.

What drew us to apply to the Hugh Hawkins Fellowship for the Study of Hopkins History?

I’m Margo Peyton, a second year Johns Hopkins medical student. I have a unique path to medical school in that I majored in English as an undergraduate and worked at DreamWorks Animation in story development before taking pre-med courses and applying to medical school. The opportunity to complete a project in the History of Medicine for the Scholarly Concentration component of our curriculum allowed me to explore an aspect of medicine that is not always a part of pre-clinical coursework and that spoke to my background in the humanities.

I’m Michael Healey, a medical student on leave from the University of Rochester. Until recently, my path to medicine was typical: I majored in biology and public health as an undergraduate in Rochester, before enrolling in the medical school across the street. During college, however, I took several courses in the history of medicine, and studied how political and institutional developments shaped the U.S. healthcare system over time. In medical school, I began to appreciate how these structural changes impacted the lives of individual patients, especially those with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia. Although I was able to take elective coursework in the history of psychiatry, I realized that the pre-clinical curriculum would not provide me with the skills I needed to critically evaluate the social and intellectual context of mental healthcare. This is why I decided to take time off from medical school and pursue a PhD in the history of medicine.

What are our research projects?

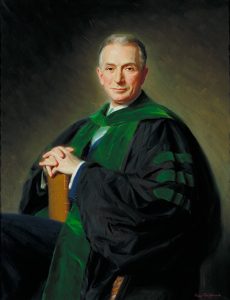

From working in animation, the visual nature of Pathology interested me from our first virtual microscopy session. I also knew I wanted to use the incredible archival resources available at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives to explore an aspect of Hopkins history. With guidance from my mentors in the History of Medicine (thank you Randall Packard, Graham Mooney, and Christine Ruggere), I chose to research Arnold Rich, the chair of Hopkins Pathology from 1947 to 1958, a world-class pathologist, and an acknowledged authority on tuberculosis. In his most well-known publication, The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis, he argued that inherent physiologic differences in black adults explained the clinicopathological differences he observed in autopsies. I wanted to explore why he made those claims.

Before I came to Hopkins, I had no intention to study the history of the hospital itself. Over time, however, I found myself drawn to the ideas and practices of Adolf Meyer, a Swiss-American psychiatrist who directed the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic from 1913 to 1941. From this influential post, Meyer promoted his own psychiatric paradigm, called “psychobiology,” which defined mental disorders as “maladjustments” to the social environment. He also trained hundreds of specialists, who spread his theories and practices at other hospitals and universities, shaping mental healthcare for decades to come. By analyzing follow-up studies conducted on patients that recovered from schizophrenia at Phipps during the 1930s, and exploring how this research influenced how Meyer’s students defined mental health later in their careers, I have tried to place Meyer’s understanding of “adjustment” under closer scrutiny, and describe how his ethical and political views shaped psychiatric care after his death in 1950.

What does mentorship for our projects look like?

While many medical students complete a project in Clinical Research, I gravitated to History of Medicine because of the breadth and depth of mentorship. I received guidance at every step from the History of Medicine department, Welch Library, Chesney Archives and the Hugh Hawkins fellowship. My archivist mentor, Andy Harrison, helped me find not only materials in the Arnold Rich collection, but also materials in the collections of those with whom Rich interacted.

This project would not have been possible without all the unique resources that Hopkins provides. All of the faculty and students at the Institute for the History of Medicine (especially Graham Mooney and Jeremy Greene) have supported me from the very start, helping me make the transition from medical education to graduate school. The Hawkins Fellowship, however, connected me to the wider university, guiding me as I conducted my first archival research. Marjorie Kehoe, Phoebe Evans Letocha, and the rest of the staff and volunteers at Chesney helped me navigate their massive collection of Meyer’s personal papers and the medical records at Phipps. Allison Seyler and the Hopkins Retrospective Program provided me with further guidance, as well as financial support and an opportunity to present preliminary findings.

What are we planning to do with our projects?

Hopkins Retrospective and the Hugh Hawkins Fellowship gave me the support and guidance I needed to investigate Rich, as well as a platform to present my findings. I will also be presenting my findings at the Medical Student Research Symposium this February.

My experience as a Hawkins fellow has prepared me well for the next stages of my project. After presenting the results of this project at several colloquia and conferences, I plan to conduct further archival research in New York City this summer, so I can learn more about Meyer’s students and the development of social psychiatry.

Why is it important to study history?

Our projects both address the thorny issue of complicating the legacy of a prominent Hopkins figure. In investigating Rich’s history, I learned how historians must straddle the line between historical empathy and condemnation of practices like racial science.

By critiquing Meyer’s understanding of mental health, and his influence over his profession, I have explored how the very definition of disease is shaped by the values of prominent physicians at institutions like Hopkins.

We hope that our research will stimulate conversation on these important figures in Johns Hopkins and Baltimore history and highlight the importance of history in modern medical practice. We encourage you to apply for the Hugh Hawkins Research Fellowships for the Study of Hopkins History!

Special thanks to the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions for providing images! To read more about the archival collections in which Peyton and Healey conducted their research, visit: The Arnold R. Rich Collection and The Adolf Meyer Collection.

If you are interested in learning more about the Hugh Hawkins Fellowship Program or the Dean’s Undergraduate Research Awards (DURA), read more here.