Enjoy this post by Yuqi Zhang, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2019-2020 academic year!

Hi, I am Yuqi Zhang (Claudia). About me: I am one of the five freshman researchers in the Special Collection Freshmen Fellowship Research Program this year. I plan to major in art history and economics, and probably minor in visual art. Hopkins attracted me because of its reputed fame in academic research, and therefore I appreciate this opportunity Special Collection provides to Freshmen Fellows that I can start my voyage of research from the very first semester of my college life!

My research subject is the nature illustrations on birds. It seems like human’s obsession of birds roots in blood. Such an enchantment may originate from an interest in the flamboyant feathers or a curiosity of flying, which associates with an underlying desire of freedom. Perhaps everyone has imagined flying freely like a bird some moments in life, of course, including me. Birds have been my childhood fantasy, but as an urban kid I had few opportunities to observe them in my life.

The earliest depiction of birds in art can be traced back to prehistorical cave paintings. In the early history of art, birds had functioned more as a delightful decorative detail or a motif, but it was not until Renaissance that they were regarded individually. From a more scientific perspective, the study of birds—ornithology—evolved from fragmented pieces of information hidden in antique works to the systematic analysis in the 18th and 19th centuries when global voyages and scientific observation prevailed.

I am currently focusing on a comparison of western and eastern bird illustrations, especially American and European versus Chinese and Japanese, based on the accessible materials. As I notice, compared to the established system of ornithology in the west, East Asian culture did not develop its own systematic study of birds in a broad dimension. Birds remained a leisure subject in art, occasionally mention in medicine books (for example, in the 47th and 48th volumes of Li Shizhen’s Compendium of Materia Medica) and sometimes act as unexpected encounters in travel notes (like Xiyu Wen Jian Lu by Qishiyi, who likely ate all the birds he met on his way to the west, except the eagles).

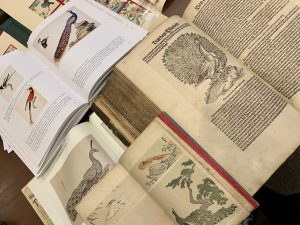

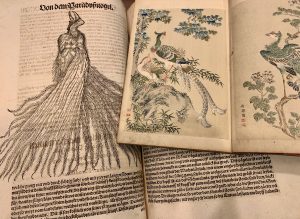

Something I find attractive is the similarity of the ways of depiction of certain species of birds across cultures. Phoenix is one striking example. This legendary bird exists in every culture I study, and the artistic depictions of it exhibit some surprising juxtapositions with one another. One illustration of “von dem paradybuogel” (“the heaven bird” that I doubt to be phoenix) in Conrad Gessner’s 16th-century Vogelbuch is similar to the phoenix in 19th-century Japanese paintings in the Bairei Hyakucho Gafu. Peacock is another favorite subject for artists, philosophers, and ornithologists across cultures. Its tail, with a rich collection of symbolic meanings, is a feature that frequently emphasized artistically by a profile presentation or sometimes an intentionally enlargement of the “eyes” on the tail.

The best part of the program is definitely the intimate, personal contact with all the rare books! Imagine turning the pages of a 15th-century Pliny’s Naturalis Historia and a 19th-century Audubon’s The Birds of America with your own hands! I also learn to request materials from Hopkins library system, and my mentor Amy Kimball is always facilitating me to find interesting materials that may relate to my research.

One challenge I am now facing is how to properly organize all the small pieces of information I have collected into a more systematic and presentable fashion. I will have to read more books on the history of ornithology for a clearer structure of the chronological context. Another challenge is that my research is more visual than verbal and literal, begetting me some difficulties in the way I should present the final project. I am considering employing my artistic skills to aid, but in which format is still undecided.