Each year Hopkins welcomes new students and faculty who may not know the history behind one of the academic world’s most renowned libraries. So, sit back as we tell the story of the Hopkins library, from the very beginning. This history will be divided into three monthly segments. This first segment covers the years 1876 to 1916.

Not long after The Johns Hopkins University opened its doors in 1876, President Daniel Coit Gilman remarked, “There is no such thing as a strong university apart from a great library.” However, the trustees decided early that they would strive to attract the best faculty possible, and buildings and other amenities would command a lower priority. The original Arts and Sciences campus, located at the intersection of West Monument and Howard streets, was close to the George Peabody Library. While this library was not then affiliated with Hopkins, it possessed an extensive reference collection and served the young university admirably, allowing President Gilman to concentrate on attracting faculty and students and setting up laboratories.

While the Peabody Library served as the University’s primary scholarly resource, Hopkins did not ignore the need for a library of its own. As early as 1874, the Trustees purchased several volumes to aid them in planning the new university. These became the nucleus of a library collection that, when Hopkins opened in October 1876, comprised just over two hundred fifty volumes. Early library directors were members of the faculty and overseeing the library was considered an ancillary duty. Perhaps as a result, the first three years saw three librarians come and go. In 1879, William Hand Browne became librarian and set about creating a first class repository. His predecessors, although of short tenure, had acquired books actively so that by 1879 the collection numbered nearly ten thousand volumes.

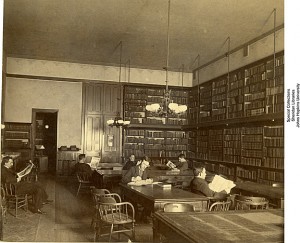

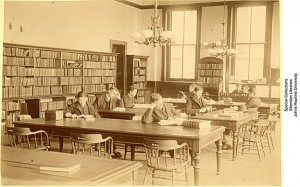

By 1891, foretelling a trend, the rooms allotted to the library, in Hopkins Hall, became inadequate. Browne resigned to resume a faculty career, and was succeeded by Nicholas Murray. President Gilman urged the Trustees to consider a new building to house the library. Just three years later, Gilman’s recommendation was satisfied when McCoy Hall opened. The library occupied the fourth floor in this large building, as well as portions of other floors. While there was a main reading room and a general collection, the bulk of the collection was divided into “departmental libraries.” In addition to book stacks, these libraries included seminar rooms lined with departmental collections. This arrangement, which was thought appropriate to the “university idea” of advanced research, became a strong tradition at Hopkins and remained in place for seventy years. In line with this plan, most scientific works were dispersed to the various laboratories. Nicholas Murray resigned in 1908, after a fire in McCoy Hall caused major damage. Handwritten accession books include the note, “Burned September 17, 1908,” for many entries.

By 1891, foretelling a trend, the rooms allotted to the library, in Hopkins Hall, became inadequate. Browne resigned to resume a faculty career, and was succeeded by Nicholas Murray. President Gilman urged the Trustees to consider a new building to house the library. Just three years later, Gilman’s recommendation was satisfied when McCoy Hall opened. The library occupied the fourth floor in this large building, as well as portions of other floors. While there was a main reading room and a general collection, the bulk of the collection was divided into “departmental libraries.” In addition to book stacks, these libraries included seminar rooms lined with departmental collections. This arrangement, which was thought appropriate to the “university idea” of advanced research, became a strong tradition at Hopkins and remained in place for seventy years. In line with this plan, most scientific works were dispersed to the various laboratories. Nicholas Murray resigned in 1908, after a fire in McCoy Hall caused major damage. Handwritten accession books include the note, “Burned September 17, 1908,” for many entries.

Murray’s successor, M. Llewellyn Raney, oversaw the rebuilding of the library and its collections. As the library grew, once again it filled its available space. This time, growth coincided with the University’s move to the Homewood Campus in 1916. The original campus had always been temporary, since there was little room for expansion.

Stay tuned for History of the Library, Part II…