My name is Lucy Massey and over the course of my Freshman year, I’ve had the opportunity to engage with several artifacts which illuminate the role of post-classical Latin (or Neo-Latin) in different historical contexts. Working with my mentor on this project, Paul Espinosa, Curator of the George Peabody Library, we discovered that Latin is anything but a dead language, and remains a powerful tool for discovery across otherwise disparate fields and centuries. Two pieces that stand out to me as exemplary of my Freshman Fellows experience are a poem by Thomas Bisse and a collection of poetry by Theodore Beza.

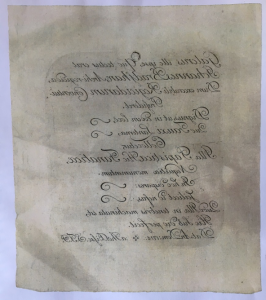

The reverse engraving of a poem by Thomas Bisse (1675-1731) is a recent addition to the Peabody Library. The poem was originally engraved on a copper plate that is thought to have been attached to the hat of John Bradshaw now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.

Bradshaw was the judge in the 1649 trial of King Charles I and, fearing assassination for his role as a regicide, lined this hat with iron plates. The hat has been in the museum since several years after Bradshaw’s death, and the poem is mentioned in a biography of Bradshaw from the 1820s as being on a copper plate with the hat. I reached out to the Ashmolean and was generously helped by Alice Howard, who informed me that the plate is no longer attached and provided this high-quality image of the hat.

Interestingly, one can see a label on the hat reading “Given by S. Bisse S.T.P. 1715. That is the year the poem is dated, but of course the author was T. Bisse, not S. The abbreviation S.T.P. refers to a theological doctorate which Thomas Bisse also held. All to say, another small piece of the puzzle to figure out. One can read more about Bisse by entering his name under the wonderful resource, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, to which the Hopkins Libraries subscribes.

The poem itself alludes to the hat residing in the Ashmolean, reading it is “fit to be placed with the lantern of Fawkes.” Guy Fawkes, Catholic architect of the failed Gunpowder Plot to destroy a Protestant Parliament in 1605, was caught with his unlit lantern in the cellars below Parliament. That same lantern was already in the Ashmolean by the time Bradshaw’s hat arrived there. Bisse draws close parallels between Bradshaw and Fawkes, labelling the former a “regicide” and the latter a “fanatic;” but he also draws attention to the difference in their actions. Fawkes’ plan to kill the king “in tenebris machinata est,” was “plotted in the shadows”, whereas the trial of Charles I “sub dio perfecit,” was “carried to completion under the light of day.” That ever so subtle difference in Bisse’s word choice (both in the ablative case) shows the way he viewed each of these figures: he reviled both, placing them in the same traitorous category, but judged them differently in terms of the boldness and cunning of their actions. Bradshaw dared to condemn a King under the glaring light of day, and in full view of his maker (dio, day here is from the adjective dius,a,um meaning both ‘charged with the brightness of day’, and ‘divine, or supernatural radiance’). Parsing out those details in Latin translation allows us to analyze how Thomas Bisse was reflecting on two major figures, already historical by his time, through the artifacts they left behind and the inflections of his Latin language skills. As you can see he was able to make some fundamental religious and historic comparisons and all in the space of thirteen lines on a hat!

| Galerus ille ipse, quo tectus erat Johannes Bradshaw, Archi-regicida, Dum execrabili Regicidarum Conventui Praesideret. Dignus, ut in eodem loco, Quo Fauxi Laterna, Collocetur, Illa Papisticae, Hic Fanaticae, Nequitiae monumentum. In hoc dispares: scilicet id nefas, Quod Illa in tenebris machinata est, Hic sub dio perfecit. Datum Anno Domini, 1715 * a Thomas Bisse |

That is the very hat, by which John Bradshaw, the Arch-Regicide, Was protected while he presided Over the detestable Assembly of Regicides. Fitting that is should be put together And in the same place As the Lantern of Guy Fawkes; That one belonged to a Papist, this one to a Fanatic, Both a monument of wickedness. To be sure each was an offense against divine law, In one thing only do they differ: That Lantern plotted in the shadows, This Hat carried out its task under the light of day. Dated in the Year of our Lord, 1715 * by Thomas Bisse, S.T.P. |

Latin Libraries

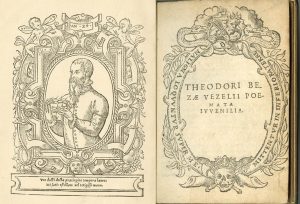

The juvenile poetry of Theodore Beza (1519-1605), French humanist and theologian, provides a unique window onto his early literary relationship with classical authors. As a precocious student in the house of the German scholar Melchior Wolmar, Beza was deeply interested in studying and emulating the great ancient authors. It wasn’t until after this collection of poetry was published that Beza’s Protestant leanings became pronounced: threatened with being burnt at the stake, he escaped to join John Calvin in Geneva. He became Calvin’s close adviser and immediate successor, as well as leading Greek education in the reformed community.

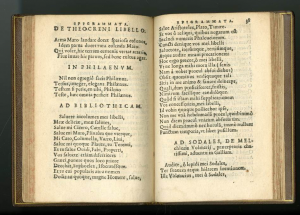

One poem in particular from Beza’s early collected works known as Juvenalia highlights Beza’s affection for the ancients. In the poem Ad Bibliothecam (To My Library) he greets each of the authors upon his shelves by name, praising them and begging their forgiveness for his absence over the past few days. Significantly, the long list of authors is exclusively ancient. There is not a single contemporary, and despite his later prominent career in the theocracy of Geneva, no attention is paid here to theological works. The composition of this poem and others in the collection also shows the strong influence of Martial, and especially Catullus – Beza went so far as to invent a Lesbia-esque muse, which brought harsh criticism from his enemies in the church. Without understanding the intricacies of Latin expression, the familiar tone of Beza’s language in Ad Bibliotecham would have been lost on me.

The list of names itself hints at his classical influences, but it is the fluid and expressive poetry that reveals the depth of Beza’s scholarship and inspiration. Here is Beza’s Latin text with my translation:

| AD BIBLIOTHECAM

Salvete incolumes mei libelli, |

TO MY LIBRARY

Greetings my little books, safe & sound, |

When taking Latin in school, I never imagined that in my first year of college I would have had any sort of fellowship opportunity, let alone the chance to work with pieces such as these. Even once I arrived at Hopkins and applied for the program, I couldn’t have guessed the wealth of resources and materials in the Sheridan Libraries. If you are interested in seeing these pieces and a few more from my project, please stop by the Special Collections Reading Room (A-level, Brody Learning Commons) where the material is on display through August 2017. Latin is alive and well here!