The first post in this series gave some general information about what a library is–we will now explore the early history of libraries. The earliest libraries we know about appeared in Mesopotamia about 5,000 years ago. According to an article in The Journal of Library History, many scholars consider the library at Ebla in northern Syria to be the world’s oldest library. These libraries held thousands of clay tablets inscribed with a stylus in a technique known as cuneiform. The tablets recorded business transactions, scientific knowledge and even myths such as The Epic of Gilgamesh. They were usually sorted in baskets or shelves according to their content. Scholars today can study these tablets from their desktop via the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative.

The first post in this series gave some general information about what a library is–we will now explore the early history of libraries. The earliest libraries we know about appeared in Mesopotamia about 5,000 years ago. According to an article in The Journal of Library History, many scholars consider the library at Ebla in northern Syria to be the world’s oldest library. These libraries held thousands of clay tablets inscribed with a stylus in a technique known as cuneiform. The tablets recorded business transactions, scientific knowledge and even myths such as The Epic of Gilgamesh. They were usually sorted in baskets or shelves according to their content. Scholars today can study these tablets from their desktop via the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative.

Moving forward many centuries, we find libraries that house scrolls written in ink on papyrus and parchment rather than inscriptions on clay tablets. Papyrus was lightweight, inexpensive, and grew well in the Nile River Delta. Moving from clay to papyrus helped spur a great increase in writing, and thus, the need for libraries to house and arrange them. The most famous library of the classical world was the Library of Alexandria, founded in Egypt by the Ptolemies in the 3rd century BCE. Demetrius of Phaleron supervised the arrangement of the library which attempted to collect all Greek literature and arrange it systematically. While we don’t have thousands of papyrus scrolls at the Eisenhower Library, we do have several excellent histories of the Alexandrian Library. The modern version of this library, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, opened in 2002 and attempts to recapture the spirit of the original while moving forward into the digital age. In addition to providing access to millions of books, the new library serves as a backup site for the Internet Archive.

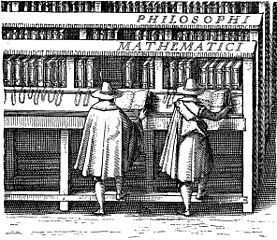

Making our way into the middle ages, we see another shift in the format of the written word: scrolls were replaced by the codex. Since the printing press was still a long way off, these books still needed to be copied by hand. European monasteries such as Monte Cassino began creating libraries of scriptures, commentaries, and philosophy, and employing their monks as scribes in their scriptoria. Don’t get the idea that a monk could just show his library card and check out a book–they were all chained to the shelf or lectern! While sacred works and classics predominated in medieval Europe, secular works such as the Roman de la Rose were also being copied and distributed widely.

Stay tuned for the final installment in this series when we will cover the great university and national libraries of today and speculate on the future of libraries.