Part of a monthly series of posts highlighting uncovered items of note, and the archival process brought to bear on these items, as we preserve, arrange, and describe the Roland Park Company Archives.

What to do with architectural drawings that are rolled too tightly to access safely? We’ve all tried at some point to unroll a tightly rolled poster. It’s usually a disaster! Unintentional creases, mountains and valleys, or worse yet, cracks. Damage aside, a tight roll snaps closed the instant we let go – not very useful for researchers. Now, what if this rolled item is not just a movie poster of our favorite flick, but an archival document that has both intrinsic and informational value? Clearly we need to proceed with more caution!

Enter paper conservation. Paper conservators learn the historic processes by which paper artifacts are made (in this case, mostly blueprints, along with some other architectural drawing types), the ways in which these artifacts break down (sometimes called the agents of deterioration), and the material properties and chemistry that can be manipulated to slow this deterioration down as much as possible. In other words, knowing what something is made of, how it is  made, and how its material properties respond to intervention, conservators can work to preserve and make cultural heritage materials accessible.

made, and how its material properties respond to intervention, conservators can work to preserve and make cultural heritage materials accessible.

Back to our architectural drawings. On a very simple level, blueprints are composed of a water-insoluble pigment on paper. For a thumbnail sketch of the science involved: paper is made of cellulose and cellulose is hydrophilic (water loving). If we introduce water vapor, the fibers of the paper will relax (water vapor is adsorbed, inter-fiber hydrogen bonds are replaced with water-fiber hydrogen bonds), and we can easily flatten the pages. If we press these relaxed papers  between absorbent material (such as blotting paper), the inter-fiber hydrogen bonds that form upon drying will be in this new flat formation, rather than a rolled formation! Of course, there are all sorts of things to keep in mind while doing this procedure – check out this link that outlines some of the cautions and pitfalls that conservators keep in mind while encountering each individual document.

between absorbent material (such as blotting paper), the inter-fiber hydrogen bonds that form upon drying will be in this new flat formation, rather than a rolled formation! Of course, there are all sorts of things to keep in mind while doing this procedure – check out this link that outlines some of the cautions and pitfalls that conservators keep in mind while encountering each individual document.

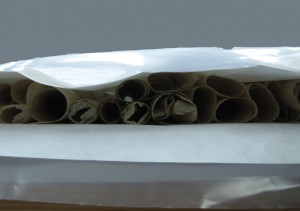

So if that’s the theory, how does it work on a practical level? Step one is to humidify the drawings. In the conservation lab, we can make use of the properties of Tyvek®, a material used to form vapor barriers of buildings – it has the handy characteristic of letting through water vapor, but not liquid water. So we build a sandwich humidity pack: plastic sheeting, a damp cloth layer, a Tyvek® layer, the architectural drawings, another Tyvek® layer, more damp cloth, and then plastic sheeting over the top. Seal this

So if that’s the theory, how does it work on a practical level? Step one is to humidify the drawings. In the conservation lab, we can make use of the properties of Tyvek®, a material used to form vapor barriers of buildings – it has the handy characteristic of letting through water vapor, but not liquid water. So we build a sandwich humidity pack: plastic sheeting, a damp cloth layer, a Tyvek® layer, the architectural drawings, another Tyvek® layer, more damp cloth, and then plastic sheeting over the top. Seal this  up around the edges, and wait! Every few hours, we open the sandwich up, ease the drawings a little more flat, check their moisture levels, and close everything back up again.

up around the edges, and wait! Every few hours, we open the sandwich up, ease the drawings a little more flat, check their moisture levels, and close everything back up again.

At the end of the day, step two is to dry and flatten the drawings in a controlled manner. We build a blotter stack (blotter, drawing, blotter, drawing….) of the damp drawings, pressing them under weight for several days. Remove them from the stack and  voila! We have flat drawings. Clean their surfaces, repair their tears, remove any pesky tape, house them in an over-sized folder, and their conservation is complete.

voila! We have flat drawings. Clean their surfaces, repair their tears, remove any pesky tape, house them in an over-sized folder, and their conservation is complete.

Next we send them back to our archives colleagues for arrangement and description…..

This is very helpful because you addressed blueprints to clearly and specifically. Now I feel confident that I can flatten our blueprints safely.

Great post. Thais process was unknown to me, thanks for the info!