Human beings are hard-wired to rely on visual perception; perhaps this explains why we really, really like to look at pictures. And when we read, we often want to see the subject we are reading about. Nevertheless, once upon a time, most reading material consisted of text without pictures. Books printed on the hand press used one kind of technology (metal type, with a raised surface for each letter), whereas the creation of detailed and long-lasting image multiples required another (intaglio methods of printing, like etching and engraving). The two technologies could not be mechanistically united. (It is possible to print a woodcut on the hand press, but woodcuts wear out and are not super amenable to fine lines.) So a finely illustrated book had to be laboriously hand-assembled by a worker at a bindery who would collate the text pages and image pages. This limitation made illustrated books fairly expensive and scarce, up until the advent of cheaper illustration processes in the nineteenth century.

So how could you feed your hunger for illustrations if you were an avid reader before the nineteenth century? Well, if you had the economic means to collect both books and printed pictures, maybe it occurred to you at some point, Hey… I can make my own illustrated books!

So how could you feed your hunger for illustrations if you were an avid reader before the nineteenth century? Well, if you had the economic means to collect both books and printed pictures, maybe it occurred to you at some point, Hey… I can make my own illustrated books!

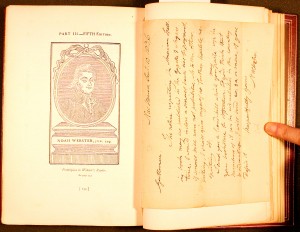

That is exactly what happened in 1769. In that year, an English parson named James Granger published A Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. Granger thought that the best way to study national history was through the biographies of Great Figures and so he developed what we might now consider a fairly insane hierarchy of twelve classes of Greats the English citizen ought to know about. (Kings and queens occupied Class I; average women showed up in Class XI; and Class XII consisted of “Persons of both Sexes, chiefly of the lowest Order of the People, remarkable from only one Circumstance in their Lives; namely, such as lived to a great Age, deformed Persons, Convicts, & c.”) Granger believed that the study of these VIPs would be aided by portraits illustrating their characters, so his book also proposed a system for collecting and organizing portrait prints. Many of his readers took his recommendation one step further and had their copies of the Biographical History rebound to include the prints they had collected. And voila: extra-illustration–also known as Grangerization–was born.

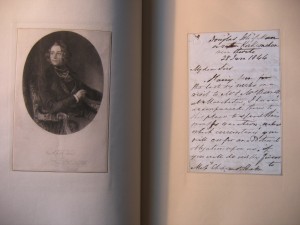

A Biographical History inaugurated a tremendous vogue in the collection of portraits that were then tipped or pasted into books. The portraits often came from other books, however, which were disassembled so that collectors could buy the plates. For this reason, extra-illustration was sometimes regarded as a destructive practice. But books were also extra-illustrated with bits of printed ephemera, manuscripts and original drawings.

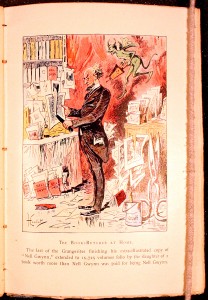

While biographies remained a favorite subject for extra-illustrators, the eclectic and personal tastes of readers ultimately determined the books they chose to practice upon. Lots of editions of Shakespeare got the treatment, for example. Bibles. Fiction, not surprisingly. Periodicals. And even after cheaper image reproduction technologies did change the economy of illustration in the nineteenth century, extra-illustrators kept on going. (In fact, they’re still at it.)

Of course I’m going to plug some of the odd and delectable extra-illustrated books we have right here in special collections. For instance, a version of John Forster’s Life of Dickens that has grown from one volume to three due to all the extra-illustrations; an edition of the picaresque eighteenth-century novel Gil Blas that includes many of the title pages of previous editions; The Croakers, an assemblage of satirical newspaper poems by a couple of Knickerbockers; Early Schools and School-Books of New England, a collection of nostalgic historical pieces about, well, early schools and school-books of New England, supplemented with pages from exercise books and textbooks and even handwritten receipts written out to school-masters. Some of our extra-illustrated books have the term “extra illustrated” in their catalog descriptions… but many of them don’t, simply because they were cataloged at a time when there was no way to track such information. So if you’d like to see more extra-illustrated books, get in touch with one of the curators when special collections re-opens August 13 in our brand-new digs in the Brody Learning Commons!

Of course I’m going to plug some of the odd and delectable extra-illustrated books we have right here in special collections. For instance, a version of John Forster’s Life of Dickens that has grown from one volume to three due to all the extra-illustrations; an edition of the picaresque eighteenth-century novel Gil Blas that includes many of the title pages of previous editions; The Croakers, an assemblage of satirical newspaper poems by a couple of Knickerbockers; Early Schools and School-Books of New England, a collection of nostalgic historical pieces about, well, early schools and school-books of New England, supplemented with pages from exercise books and textbooks and even handwritten receipts written out to school-masters. Some of our extra-illustrated books have the term “extra illustrated” in their catalog descriptions… but many of them don’t, simply because they were cataloged at a time when there was no way to track such information. So if you’d like to see more extra-illustrated books, get in touch with one of the curators when special collections re-opens August 13 in our brand-new digs in the Brody Learning Commons!