In our recent Incredibly Helpful Hints post, we noted that “we like to keep you on your toes” with quartos. But what makes a “quarto” or a “folio” different from a regular book? Sure, they’re bigger, but why the distinction? Don’t worry; it turns out we’re not just trying to confuse you!

In our recent Incredibly Helpful Hints post, we noted that “we like to keep you on your toes” with quartos. But what makes a “quarto” or a “folio” different from a regular book? Sure, they’re bigger, but why the distinction? Don’t worry; it turns out we’re not just trying to confuse you!

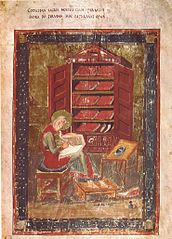

The modern books (not including e-books, of course!) are codices (singular: codex). According to the Getty’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus Online, codices are “bound leaves of paper or parchment with information inscribed on both faces.” With the rise of Christianity, the sturdier codex became the format of choice, replacing the papyrus scroll in the first century of the Common Era. (Also, it’s not so easy to find a specific passage in a long scroll!)

In the Middle Ages, the pages of a codex were made from parchment, that is, animal skin, usually sheep or calf. To learn the specifics of how the skin of sheep became a medieval manuscript, check out MSEL’s copy of Scribes and Illuminators by Christopher de Hamel. In the medieval period, book formats were dictated much more by the materials used, and really, how many animals were available. For example, one especially large and luxurious manuscript from the early Middle Ages, the Codex Amiatinus, used skins from over 500 individual animals!

Now, here’s the answer to our question! To make the book format called a “folio,” you fold the parchment sheets once which makes two leaves or four pages (A leaf or folio is numbered on one side only while a page is numbered on both sides). Folding the sheet twice makes a “quarto,” four leaves or eight pages. And folding it one more time makes an “octavo,” which translates into the size of the standard paperback we’re accustomed to using. The names stuck–while these terms were originally related to how books were made, they came to signify the size of the book. So, paper books printed today still have a relationship to the way books were produced almost two thousand years ago!

If you’re interested in medieval manuscripts, here’s some really exciting news: there are more and more projects every year to put entire manuscripts online so that you can virtually flip through the pages—something you can’t always do with an actual 11th century book! For a few examples, check out the Roman de la Rose website, the Walters Art Museum’s digitized collection of manuscripts, the British Library’s Digitised Manuscripts, or the Digital Abbey Library of St. Gallen. All of these sites are great resources, but, if you’re leaning towards an art history topic, don’t forget about the library’s Art History Resource Guide, and for manuscripts owned by the Sheridan Libraries, check out our Special Collections and Archives.

Now, the next time the catalogue tells you the book you need is a “quarto,” you’ll know the where and the why!