We all know what happens to the losers in the canon wars: their works are relegated to the lowly position of “minor” literature. William Gilmore Simms, anyone? A nineteenth-century South Carolingian novelist that Edgar Allan Poe admired, Simms’ support of slavery—and his much publicized opposition to Uncle Tom’s Cabin—put him out of sync with the culture as time went on. Plus, maybe he wasn’t such a great writer. (Try reading The Partisan: A Tale of the Revolution to see if Simms really is “the Southern James Fenimore Cooper.”) Nevertheless, the fact that he was extremely popular at one time, and extremely prolific, means that we have a lot of Simms’ books in the library collection.

But what about the writers who weren’t even invited to the fight? How do we revive those works—works that maybe only appeared in ephemeral forms like broadsides or magazines, or in a small initial print run? Works that never appealed to a broad readership, or never had the benefit of mainstream approval? Sometimes, through great effort, some of this literature can be pulled out of the black hole of historical obscurity and given back to readers, allowing us to reconsider its value. One example of such an effort would be the Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers, a series under the general editorship of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. These works had virtually disappeared, but have become available to twentieth- and twenty-first century readers because the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture had in its collections a vast quantity of fragile primary source material that could be resuscitated in print.

Here in the Sheridan Libraries, we like to take on similar challenges. We acquire contemporary re-issues of out-of-print works that are still valuable to scholars, and works that were never published in their authors’ lifetimes. We also carry out our own primary source investigations. It’s fascinating to discover what we have and what we are missing from the past. We have quite a few early editions of works by the writers of the Harlem Renaissance, for example, like Harlem Shadows: The Poems of Claude McKay, published in 1922. Some of these works were acquired by the Peabody Library back when they were first issued, perhaps because the librarians were paying attention to local critic H. L. Mencken, who supported the Harlem Renaissance writers—even though general popular opinion was not strongly in their favor.

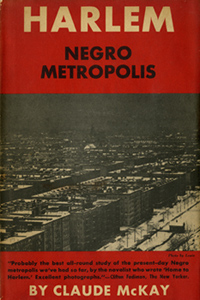

McKay is best known for his lovely sonnets, and that’s what our collection generally reflects. But poetry does not comprise the entirety of his literary output. To help fill in the gaps, we recently acquired Harlem: The Negro Metropolis, a sociological essay McKay wrote in 1940. Illustrated with documentary photographs and peppered with McKay’s anti-Communist views, it makes a striking counterpoint to the poetry.

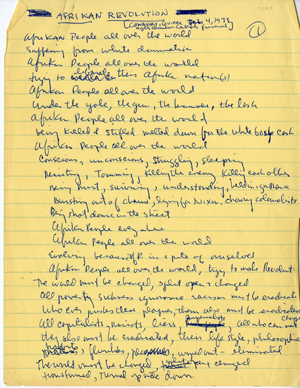

Sometimes what’s missing isn’t the work itself but its story. Another recent acquisition is the manuscript and first pamphlet printing of Amiri Baraka’s 1973 poem “Afrikan Revolution.”  Although this poem was later published in the 1979 collection Selected Poetry, and can also be read in later anthologies like The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, the manuscript and the pamphlet show the poem in its emerging form and original print context. The poem essentially becomes a series of poems—a poem in motion—when we read it within these changing textual and historical environments.

Although this poem was later published in the 1979 collection Selected Poetry, and can also be read in later anthologies like The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, the manuscript and the pamphlet show the poem in its emerging form and original print context. The poem essentially becomes a series of poems—a poem in motion—when we read it within these changing textual and historical environments.

Of course, we couldn’t possibly hold within the library walls all the many versions of all the many literary works that our community finds interesting. And we can’t—and shouldn’t—rescue everything that falls into historical obscurity. But peering over the edge of that black hole, fishing out a book now and then? Pretty amazing to think that on such small acts of chance and vigilance the future of history depends.