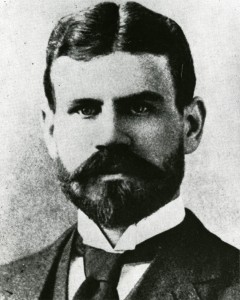

In the Alumni Memorial Residences on the Homewood Campus, there is a dorm house named for Jesse Lazear, who was described upon his death as “a martyr in the noblest of causes.” While Walter Reed gets credit for solving the mystery of how yellow fever and malaria are transmitted – and he deserves credit – Jesse Lazear was also heavily involved in this research, so heavily involved, in fact, that he lost his life in the cause of medical research.

Jesse William Lazear was born in Baltimore in 1866. He earned his bachelor’s degree at Johns Hopkins University in 1889, followed by an MD from Columbia in 1892. Returning to Hopkins after further study in Europe, he was appointed bacteriologist in the School of Medicine. In February 1900 he was appointed assistant surgeon with the US Army and ordered to Cuba. The Spanish-American War had recently concluded, bringing independence from Spain to Cuba, and troops were still stationed on the island.

During the war, many more died from yellow fever and malaria than from battle wounds, and the Army was determined to find out what caused these diseases. The prevailing opinion held that bacteria were the cause, spread through contact with clothing and bed linen used by patients. A few researchers theorized that mosquitoes were the real culprit, but most scientists believed in the bacteria theory. While the Army had a vested interest in conquering these diseases, they were not just a problem in tropical areas. Cities along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts were affected, including Baltimore and as far north as Philadelphia and New York.

Lazear, working under Dr. Walter Reed, set out to test the bacteria theory. While working at Hopkins, Lazear had become interested in this question, and had familiarized himself with the research of Cuban scientist Carlos Juan Finlay, a leading proponent of the “mosquito theory.” Intensive research soon disproved bacteria as the cause of yellow fever and malaria, so Lazear quickly shifted to the mosquito theory. Picking up on the research of Finlay and Sir Ronald Ross, Lazear conducted a series of experiments proving that certain types of mosquitoes transmitted a virus that caused yellow fever and malaria. Next began the work to develop a vaccine.

Lazear, working under Dr. Walter Reed, set out to test the bacteria theory. While working at Hopkins, Lazear had become interested in this question, and had familiarized himself with the research of Cuban scientist Carlos Juan Finlay, a leading proponent of the “mosquito theory.” Intensive research soon disproved bacteria as the cause of yellow fever and malaria, so Lazear quickly shifted to the mosquito theory. Picking up on the research of Finlay and Sir Ronald Ross, Lazear conducted a series of experiments proving that certain types of mosquitoes transmitted a virus that caused yellow fever and malaria. Next began the work to develop a vaccine.

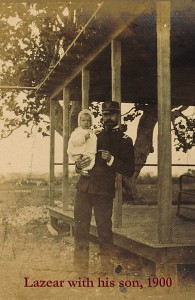

The official story is that Lazear became accidentally infected with yellow fever while working on a vaccine. According to some of Reed’s writings, however, a journal kept by Lazear (which disappeared after Reed’s own untimely death in 1902) indicated he may have deliberately allowed himself to be bitten by a mosquito from his laboratory. Whether accidental or deliberate, Lazear contracted yellow fever. He wrote to his wife on September 8, 1900, that he believed he was on the right track, and he may have already been infected. On September 25, 1900, he died, leaving a widow, a one-year-old son, an infant daughter, and a promising future.

Closer to home, in 1915 as the Great War in Europe was escalating, Baltimore was abuzz. Not with concern over U.S. involvement in the conflict, but with mosquitoes. Mayor Preston had written to the surgeon-general of the United States Army, William C. Gorgas, asking for help in exterminating the mosquito population.

Gorgas had spearheaded a campaign against the yellow-fever carriers in the Panama Canal, and Preston hoped he would be able to cure the Baltimore blight. Gorgas directed Dr. Henry R. Carter, head of the U.S. Marine Hospital located in Remington, to investigate the problem. Carter had worked with Gorgas in the Panama Canal and in 1903 conducted extensive research on the Baltimore mosquito. He assured the mayor and the city that Baltimore mosquitoes were “harmless,” except where the Jones Falls flowed through the northernmost part of Remington. However, Carter was convalescing at Johns Hopkins Hospital and could not physically take part in the eradication program. Instead, William D. Wrightson, who also served with Gorgas in Panama, was appointed to oversee the physical operation.

Wrightson, a Baltimore native, was also son-in-law to Gorgas and would again serve under him in the U.S. Army Sanitary Corps when the United States entered the war. He was supervising a similar operation in New Orleans when he accepted the position. On his way to Baltimore, however, he was stricken with appendicitis and had to convalesce in a Washington, D.C. hospital. It seemed the mayor was unable to raise the army he need to fight the ’skeeter war. Finally, the commissioner of street cleaning, William A. Larkins, was appointed temporary supervisor in March 1915. One of his first stops was Remington.

Conditions were perfect for mosquito breeding as most of the northern portion of the community was in the first stages of development, and construction had left large pools of rainwater to accumulate on the planned lots. In addition, houses along the Twenty-eighth and Twenty-ninth Street corridor were five feet below street level due to roadwork, and Sumwalt pond (south of the Homewood campus) was overflowing into the yards of these homes. Feather beds, mattresses and tables were found to be floating about with outhouses. Water was so deep in some areas that children were playing on rooftops. Larkin, along with a couple city engineers, decided that draining and sewering the standing water was the best line of attack, and the mayor agreed. He had been trying to budget for sanitation improvement in Remington since he began his term, and this looked like an opportunity to kill two ’skeeters with one blow. The task proved formidable as new infestations along the Stony Run and Jones Falls were discovered. Remingtonians were worried about malaria from the Jones Falls mosquitoes, although they had been abiding the pests for generations. The Public Health Service announced that Sumwalt Pond, then owned by the City Dairy Company, was capable of developing enough mosquitoes to infest half of Baltimore. To allay some fears, Larkin had Sumwalt Pond drained and filled immediately. All through that spring and summer, city workers crowded the streets of Remington, pouring kerosene in small pools of water, draining the larger ponds and handing out thousands of leaflets telling the community how to combat the thick clouds of the critters that had descended on the neighborhood.

As fall approached, the mayor was getting frustrated by the campaign’s lack of cooperation from Baltimore citizens and started fining householders that maintained mosquito-breeding places on their property under an ordinance he had passed that summer. Remingtonians were outraged that they were being targeted as the culprits in the matter and demanded the mayor hold to his promise of a new sewer line for Remington Avenue. Neither side budged in their demands as the war on mosquitoes continued until winter when most of the pests lay dormant.

As new development was being completed in north Remington, some of the mosquito population abated, but be careful as approaching the Stony Run, because those little bloodsuckers are still about!