What does the old school picture postcard have to do with modern photo- and video-sharing platforms like Instagram and TikTok? Nothing, on the face of it. But, arguably, the postcard is the very technology that got us to where we are now—especially if you consider the “real photo postcard,” a special variety of photographic postcard that developed as part of the “postcard craze” of the early twentieth century. While postcard publishing companies produced an increasing number of photographic cards from which consumers could choose during these decades, these images often left out or distorted—like so much of mainstream mass culture—the Black experience.

Real Photo Postcards and Black Experience

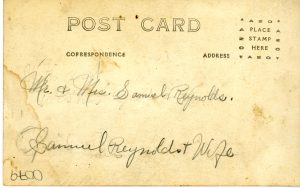

The commercial photographic postcard is a reproduction of a photographic original printed onto cards—usually, a LOT of cards, so that the publisher can recoup the cost of production by selling many copies. Real photo postcards, in contrast, are actual photographs printed from a negative onto a postcard backing. A real photo postcard might exist as a single artifact or in a small edition. During the years when real photo postcards were popular, consumers paid a small fee to have them printed—so there was no publisher in the mix, hustling their ideas about what would sell.

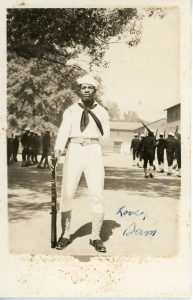

The real photo postcard’s production technique and business model meant that, long before social media made it possible to record and share selfies, people could turn their own photographs into postcards to send through the mail. It was a great way to distribute images that reflected your lived reality, not what a commercial postcard company put on the market. The real photo postcard gave African American correspondents of the first half of the twentieth century a way to avoid the racist imagery that permeated much of popular culture and replace it with self-created imagery.

The African American Real Photo Postcard Collection at JHU

The African American Real Photo Postcard Collection at the Sheridan Libraries contains over 1000 real photo postcards that portray Black subjects from the early through the mid 1900s. Some of the images are snapshots, presumably taken by a friend or family member; some were made in photo booths; and some are carefully staged portraits taken by studio photographers. Some are blurry, crooked, or over-developed—true amateur photographs from a time when operating a film camera required technical know-how and practice. Some show people at home or on vacation; some document major life events like family reunions and graduations. Often, the people in these images look sober and formal, reflecting the belief, common in this period, that a portrait was an occasion for serious self-presentation. Some images, however, show people dressing up in costumes or playing with props, having fun and cracking up.

There are a few cards in the collection with posed racist stereotypes produced at small-scale tourist attractions, and one postcard depicts a lynching. These are grim reminders not just of the threat of terror and degradation that has shaped Black life but also of the taste of many white Americans for violent racist imagery.

There’s a lot we don’t know about these postcards. Many were never mailed, and very few of them contain information that identifies the subjects, the location, and the date of creation.

We acquired the collection from a rare books dealer who got it from a collector who built it over years through the ephemera marketplace, at venues like estate sales and postcard fairs. So, the provenance of the collection doesn’t tell us much about the postcards’ origins.

Despite the absence of contextual information, these postcards can be incredibly valuable for research about Black life in the first half of the twentieth century. Images taken in front of or inside residences, for example, illuminate the African American relationship to domestic space at a time when the Jim Crow practice of redlining erected obstacles to Black home ownership. Portraits show people in their best attire, or sometimes in more informal dress—important visual clues about clothing and style in everyday life. Photographs taken at destination sites, on vacation, or while relaxing in the backyard can advance the analysis of Black leisure. And, of course, to our screen-saturated eyes, it’s fascinating to uncover the roots of our contemporary obsession with self-portraiture. That’s precisely how two undergraduates used the collection in their exhibition American Selfie a couple of years ago.

How to Use the Collection

- If you are interested in doing research with the African American Real Photo Postcard Collection, you can request the boxes and make an appointment to examine the physical artifacts in the Special Collections Reading Room. Or examine the digital reproductions in the university’s institutional repository, JScholarship.

- The digital collection is organized by browsable general subject categories. You can also use keywords to search across the entire digital collection, but since we don’t have a lot of detail to apply to these images, the metadata doesn’t support very granular keyword searching.

- When you do research with this collection, please respectfully consider that these postcards might depict people who are still alive or recognizable by their descendants.

- Due to the absence of information about the dates of most of these postcards, we don’t always know which images might be protected under copyright and which are in the public domain. For information about rights and reproductions, please refer to the Sheridan Libraries Digital Asset Use, Rights, and Permissions policy.