Enjoy this post by Romila Detering, one of our Special Collections First-Year Fellows for the 2024-2025 academic year. Applications for the 2025-2026 cycle are now open!

I am excited to conclude my first year at Hopkins with a final semester of being a first-year fellow! Continuing to analyze yearbooks, student transcripts, application documents, and directories has shifted my perspective on admissions and opened my eyes to the experiences of a less-researched group of students at Hopkins. Being a fellow has given me access to Hopkins’ complex and challenging history of being a globally recognized university with a focus on its presence in Baltimore. Working alongside the other fellows and my amazing mentor, Brooke, has introduced me to the merits of interdisciplinary archival work. I can’t wait to apply these research methods to my future research at Hopkins.

I began my research by paging through the Johns Hopkins Half-Century Directory, 1876-1926 and the corresponding JHU Hullabaloo yearbooks to identify international students. I then selected individual students and analyzed their individual application materials and transcripts upon graduating. I analyzed these student records throughout most of my time as a fellow, as the documents in each student’s file ranged from high school grades to letters to the alumni association post-graduation. Alongside these key documents, I analyzed other primary sources, like the JHU Registers.

This semester, I looked at other international students while also aiming to contextualize the Progressive Era by analyzing documents I hadn’t looked at last semester: the JHU Registers and the Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman. The relevancy of Hopkins’ initial preference to admit students “at first, at home, in Baltimore and Maryland; then, in the States adjacent; then, in the regions of our country…” became apparent as I observed difficulties that international students faced in applying to Hopkins.

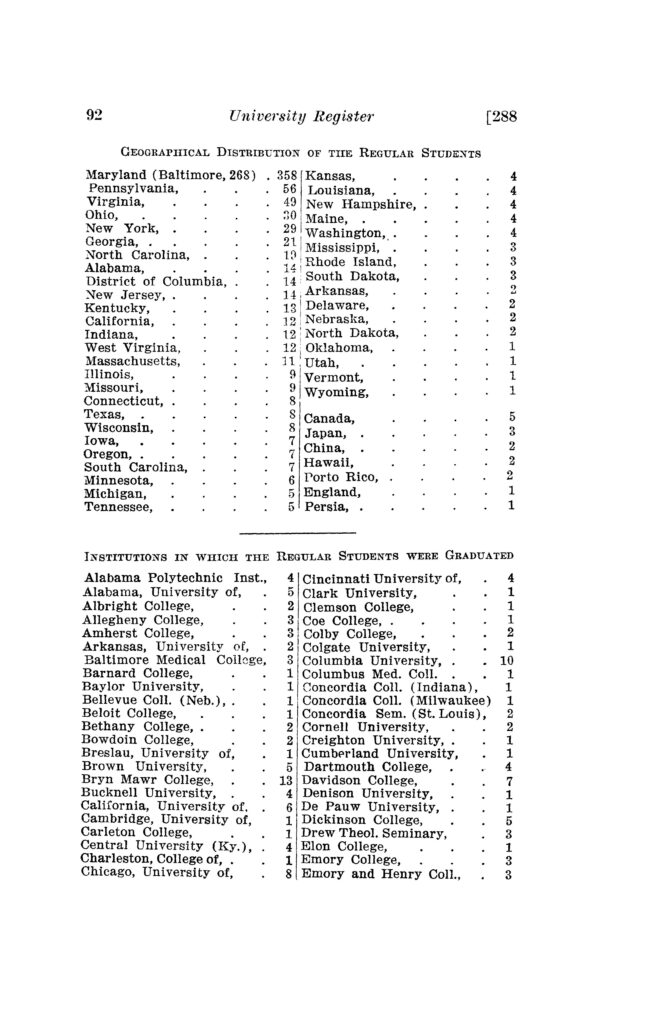

The 1913 JHU Register provided important insight into the proportion of the Hopkins undergraduate population that was international. The 1913 Register revealed that only 16 of 788 “regular students” (= 2.03%) were from places outside of the continental United States, while 358 (= 45.43%) were from Maryland alone. Only 12 students (= 1.52%) were international. The distribution of nationalities also helped me wholistically understand the individual students I examined: most international, non-Native English-speaking students applied from East Asia.

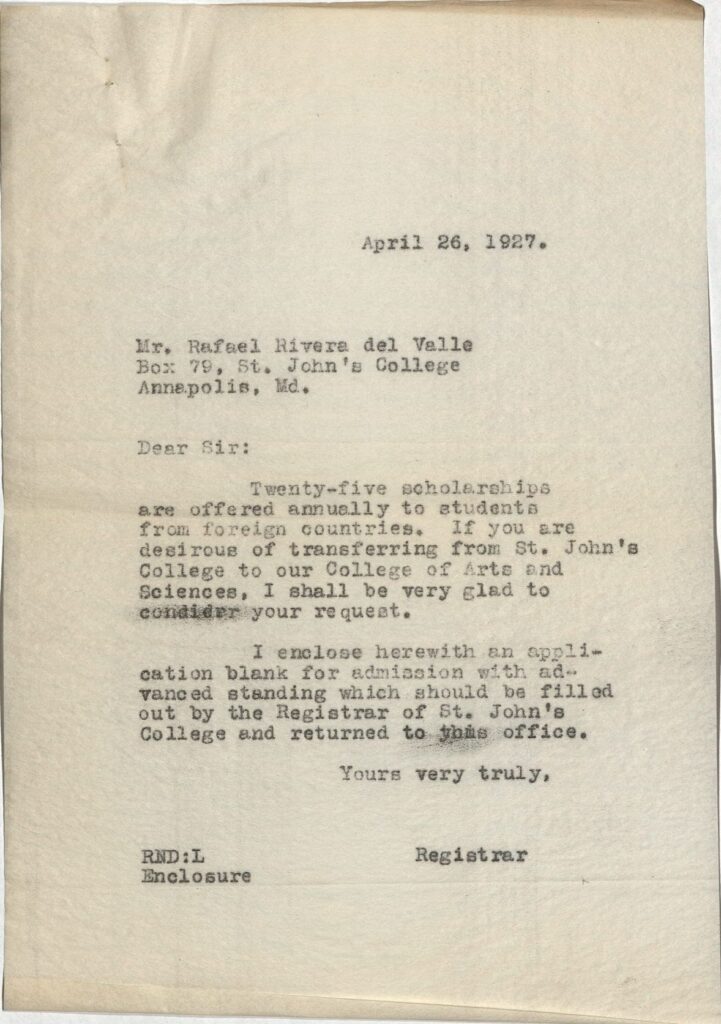

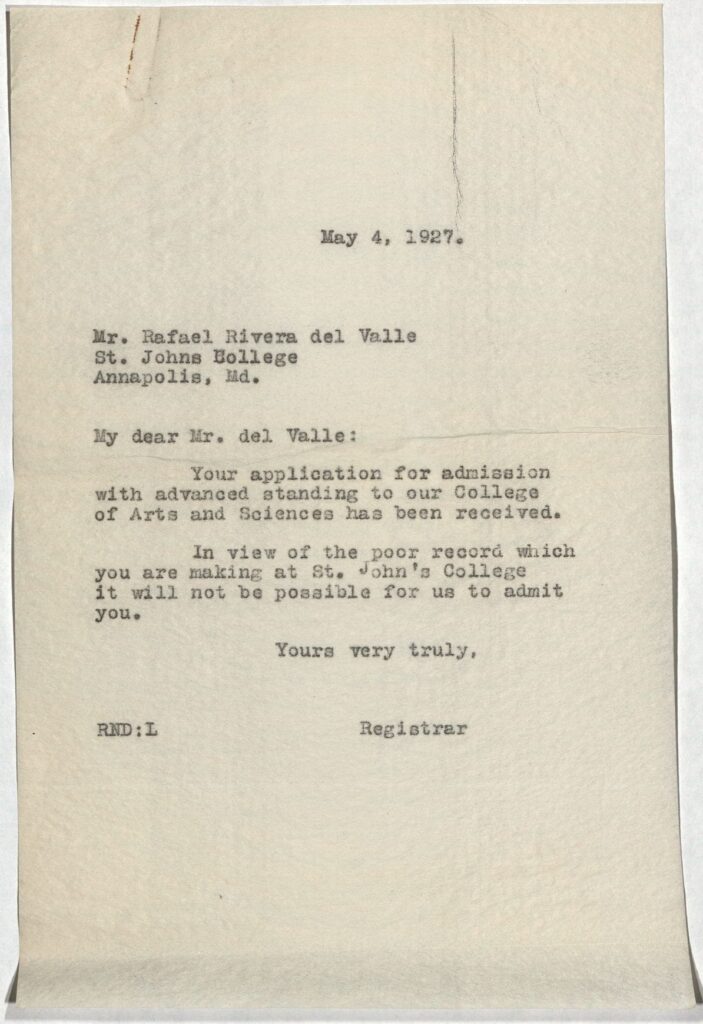

Surprisingly, I came across the files of an international student who was rejected for admission with advanced standing, after applying as a transfer student from St. John’s College in Annapolis. These files are not typically preserved in the collection. According to the Registrar’s April 26, 1927 letter to Rafael Rivera del Valle, from Puerto Rico, JHU offered twenty-five scholarships “to students from foreign countries.” While del Valle was not admitted and did not receive the scholarship, due to his poor college record, the offer of a scholarship does represent the university’s commitment to ensuring international students’ success.

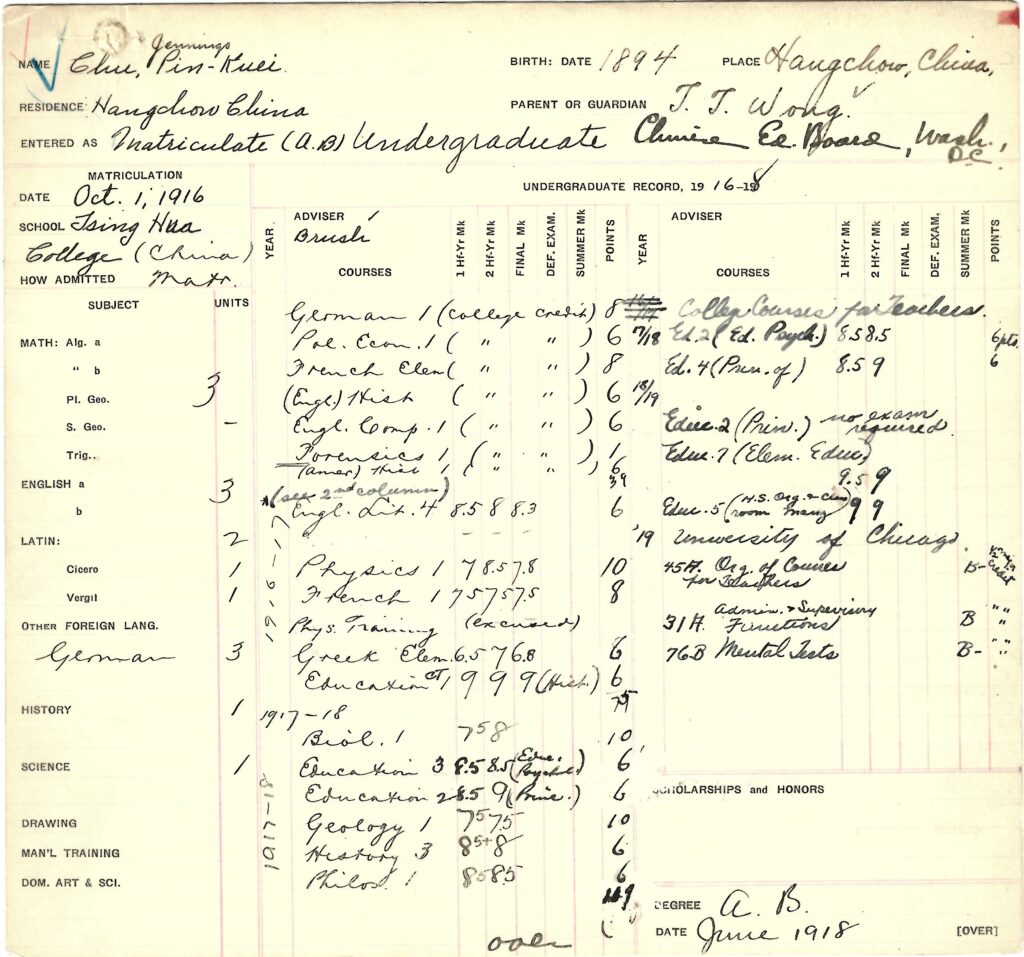

However, I also compared international students’ transcripts to better understand language-learning difficulties at Hopkins. While Carl Jefferson Weber, a German student, succeeded in his foreign language classes by receiving top grades in Greek, German, and Latin, he likely benefitted from his prep school education and previous time spent in Baltimore. I compared this transcript to Jenning P. Chu’s transcript, which I had looked at briefly before. Chu received low grades in foreign language classes, unlike Weber. In Greek and English literature, Chu received a 6 out of 10 possible points. In German and French, he received a score of 8. These difficulties can possibly be attributed to the high expectations JHU had in requiring international students to master English and additionally learn other languages.

My research of early international student records led me to a few key conclusions. JHU was not intentionally discriminatory towards international applicants, and in some ways, even encouraged international students to apply. Still, JHU failed to properly accommodate admitted international students, as many struggled to grasp the multiple foreign languages they were expected to learn. Gilman’s statement highlighted the preference Hopkins gave to domestic applicants, and the consequential disregard for international applicants. Finally, my work with JHU’s Hullabaloo yearbooks emphasized the casual racism from American (domestic) students that many international students faced. Yearbook contributors jokingly included much of this casual racism in the graduating international students’ yearbook descriptions, but it appears harsh and insensitive from a modern perspective.

I wish I had had the opportunity to analyze every single international student’s records during the Progressive Era (since, after all, there were very few every year). Still, the trends I identified were strong and evident in the files I did have the chance to examine. I am still in awe of the depth of each file and the impressive collection of letters, pictures, envelopes, and grade cards that the JHU Special Collections possesses. Being able to highlight some of the very first international students at JHU is a privilege and honor, especially in light of the recent difficulties international students have faced during the last few months of changing immigration politics.

I look forward to continuing my research on immigration as a Woodrow Wilson Fellow, which will lead me to analyze the German perception of Ukrainian refugees to better understand German conceptions of race and culture. While my project will rely less on archival methods and more on ethnographic methods, I will continue to bring forward individual stories of integration into foreign communities.

I am, as always, extremely grateful to my mentor, Dr. Brooke Shilling, who has helped me navigate the complicated process of identifying international students and primary sources. I am also thankful to Hopkins Retrospective for so actively engaging with my work and highlighting my First-Year Fellows research on their Instagram page. I am excited to continue visiting the Special Collections and can’t wait to see the next First-Year Fellows carry on vital archival research!