Enjoy this post by Maneeza Khan, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2023-2024 academic year.

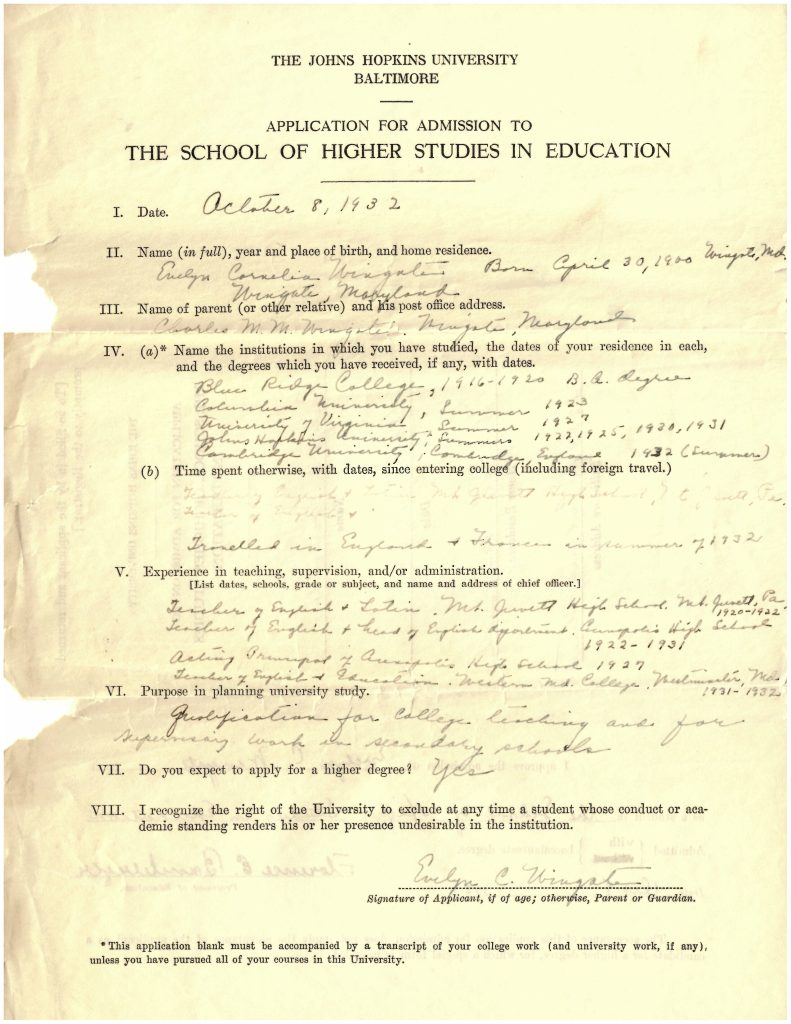

My eyes widened in awe as I read the impressive accomplishments of Evelyn Wingate Wenner, who at the age of 37, had pursued a Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, and numerous summer courses from prestigious institutions including Johns Hopkins University, Columbia University, University of Cambridge and University of Virginia (Fig. 1). Her testimonials (this is what we call letters of recommendations today!) spoke highly of her, highlighting her as a trailblazing academic and naming her dissertations as “revolutionary”. Evelyn Wingate Wenner was one of the first women to obtain a degree from Johns Hopkins, and from my research of the earliest student files from 1876 to 1943 in the records of the Office of the Registrar, she certainly was not the last.

My love for research of archival studies has thrived ever since I spent two summers researching university archival records at the Bodleian Libraries Special Collections. One of the main reasons is because archival records provide a beautifully intimate insight into the hopeful dreams and inspiring journeys of historical individuals who paved the way for diversity, equity, and inclusion at world-class institutions.

Before we begin diving too deep, please allow me to introduce myself! My name is Maneeza Khan, and I plan to double-major in Molecular and Cellular Biology and Public Health. I have been honored to be conducting research with Special Collections as a Freshman Fellow with Dr Brooke Shilling as my mentor.

I know that my passion for archival studies research may seem unconventional for my aspiring academic path. You might be wondering: how are Biology and Public Health even related to archival studies? To preface, as Hopkins students, we have an undeniable responsibility to broaden our knowledge and perspectives on the way the university has progressed to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus. I believe that university admissions play a major role in upholding these values and therefore, we must gain a deeper understanding of Hopkins’ historical journey in making its admissions process more progressive. From a personal standpoint, this issue is extremely dear to my heart. I am a proud first-generation Muslim student and am incredibly grateful for the people who came before me and forged a trailblazing path that has inspired generations of students like me to pursue a college education despite societal barriers. Therefore, it is my greatest honor and responsibility to be involved in such an important field of research.

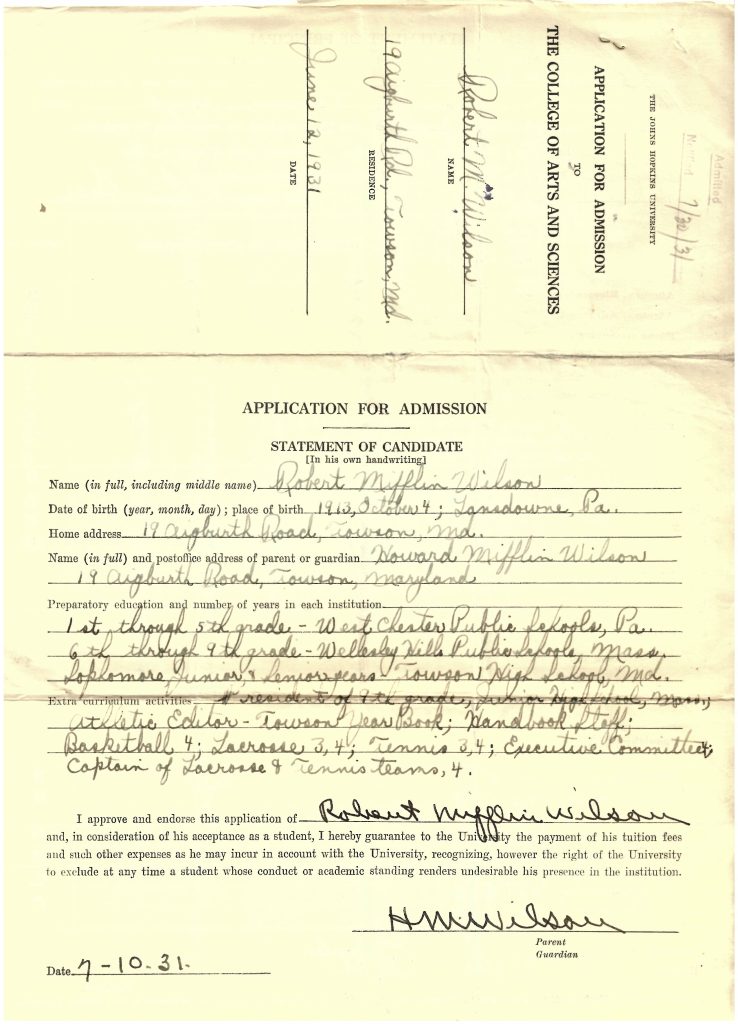

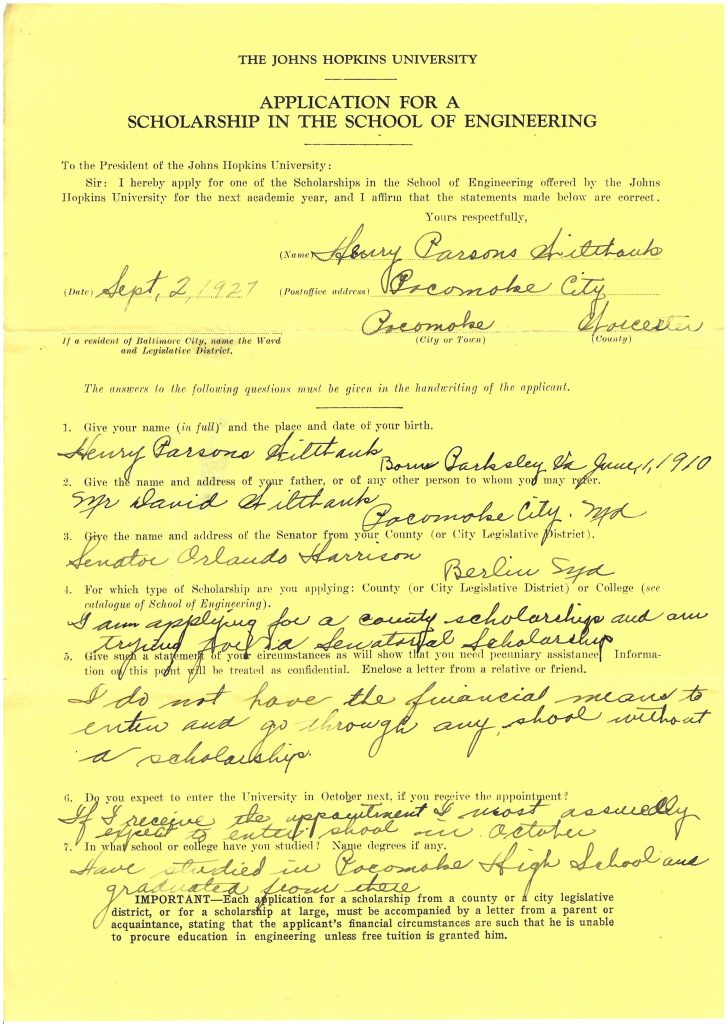

One of the first aspects of the admission process I noticed was that general application questions related to demographics were limited to the date and place of birth and home address of parents/guardians (Fig. 2). Because the national affirmative action policy was not adopted until the 1960s after the Civil Rights Movement and because student files after 1943 are not yet open for research, there was a distinct lack of demographic questions such as race, socioeconomic status, religion and other such aspects that are prominent in modern-day university admission applications.

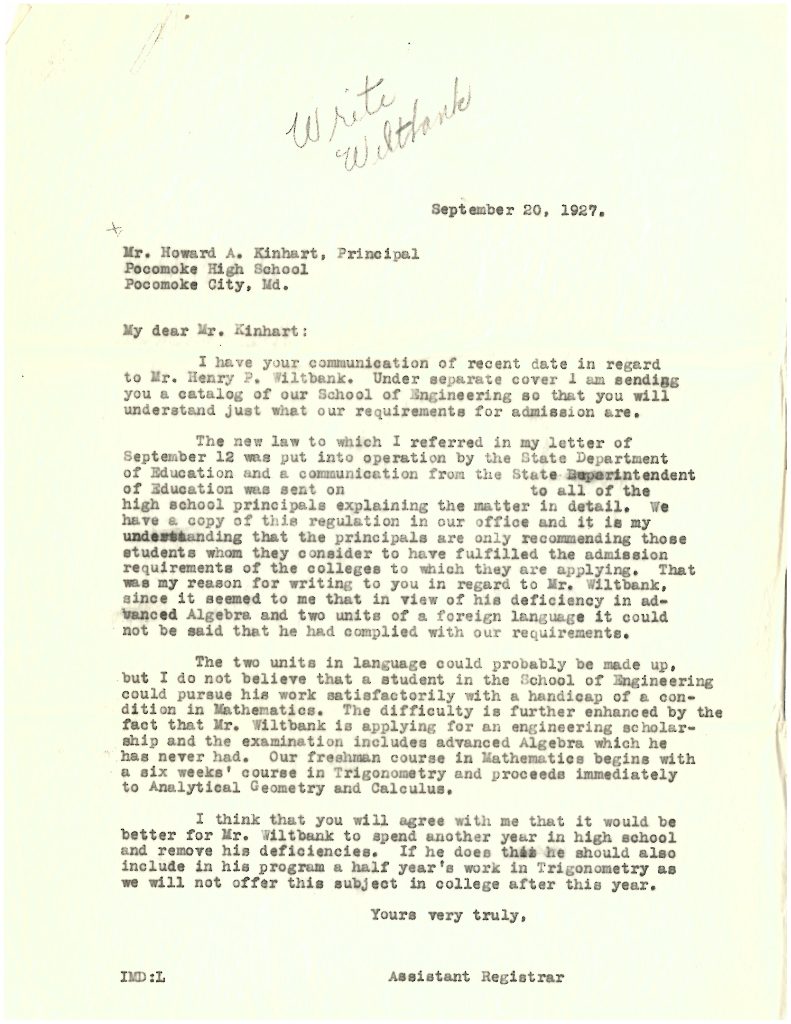

Additionally, the applicant’s academics in the form of diplomas, academic certificates, and summer courses were highly valued, and there were many specific course requirements that applicants had to take in high school before even considering applying to Johns Hopkins. In fact, I discovered many fax correspondences between prospective applicants and the Office of Admissions asking applicants to take additional high school courses for their applications to be eligible for admission review (Fig. 3). Some of the academic requirements were 4 years of Latin, 3 years of Mathematics, 4 years of English, and 2 years of History. The academic requirements were more specific for different schools, which is similar to what modern-day admissions look like.

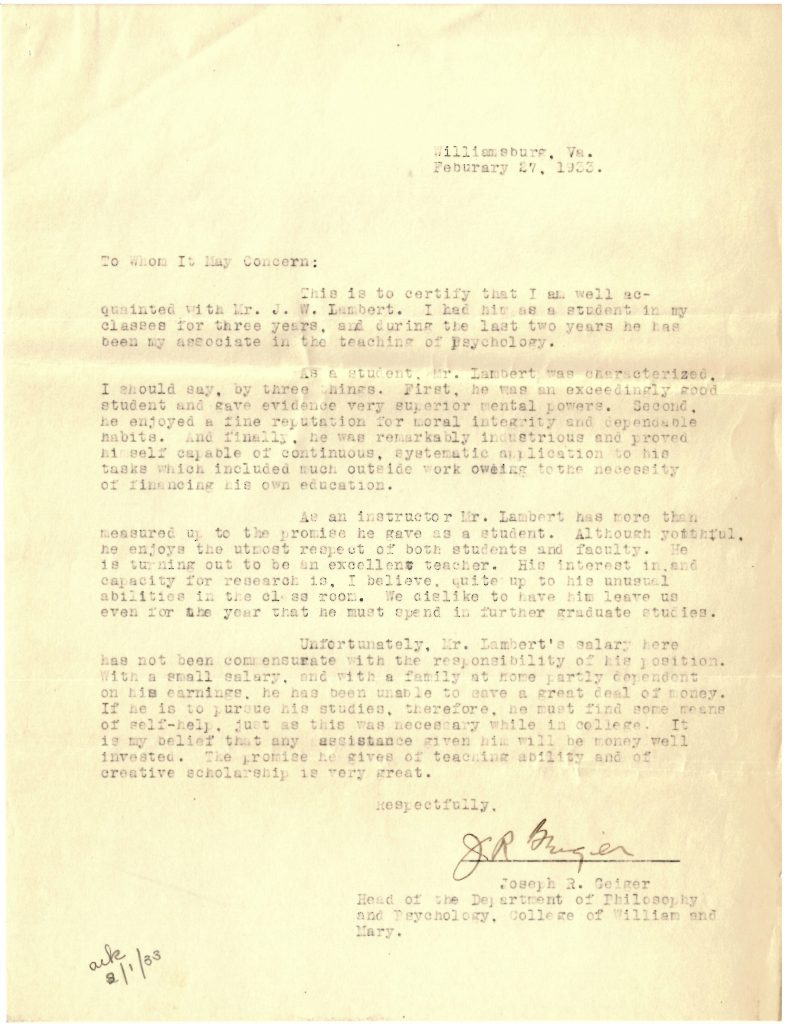

While academic information was a major component of the application, there were certain components, depending on the type of application, that allowed applicants to highlight their passions and personal journeys. These included testimonials (known as letters of recommendation today), oral examinations (known as interviews today), and short “personal questions”. I was incredibly excited to read these components as it allowed me to take a glimpse into the motivation and drive of students who helped shape the legacy of the university. For instance, a man named J. W. Lambert applied for Doctor of Philosophy in 1929 and his testimonials spoke highly of his moral integrity and dependable habits, highlighting him as “remarkably industrious” and commending his “unusual abilities in the classroom” (Fig. 4). Moreover, I noticed that scholarship applications valued student experiences and character more highly than general admission applications, as they required a minimum of 3 testimonials that advocated for the applicant’s “character, scholarship, and need of pecuniary assistance” (Fig. 5).

It has also been incredibly exciting to understand the variations of applications among academic groups, and later, schools. To briefly highlight some of my interesting findings, I found that the School of Engineering did not have a separate undergraduate application until the late 1910s and the Application for Admission to the College of Teachers was one of the most extensive applications of its time!

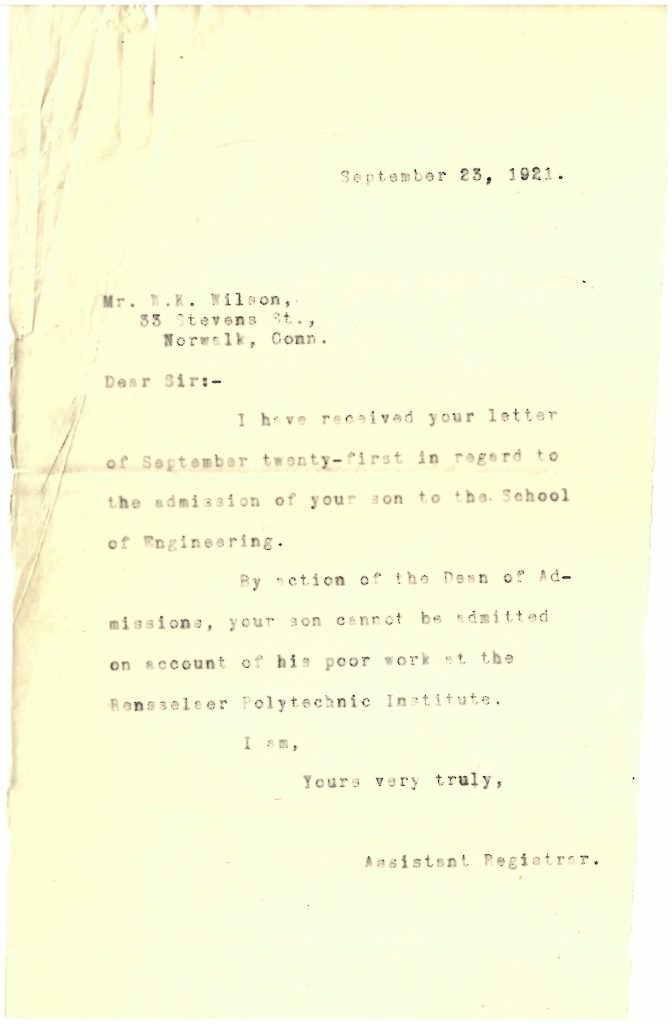

My most thrilling finding during my time as a First Year Fellow until now has been discovering rejected applicant files in the Office of the Registrar (Figs. 6-7). For context, rejected applicant files are not typically retained by the university. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised to discover not just one, but multiple rejected applicant files in the Office of the Registrar boxes! I could barely contain my excitement when I informed Dr Shilling, who was also thrilled by this finding. Experiences such as these are what motivate me to continue researching the history of our institutions through their archives, as you may never know what discoveries you find!

Upon discussion with Dr Shilling, I plan to focus on two areas of the early student files: (1) the presence of female applicants in the early student files, and (2) scholarship applications and their role in admitting economically disadvantaged applicants over the decades. I intend to share my research findings on my investigation with the Hopkins and the greater Baltimore community by presenting at research symposiums and student showcases. Through this, I hope to educate our communities on the longstanding efforts by the institution to make university admissions more diverse and equitable and inspire them to preserve that legacy.

My blog post would be incomplete without me expressing my sincere gratitude to my mentor Dr Brooke Shilling for her remarkable guidance and mentorship. Dr Shilling has been a wonderful pillar of support for me, be it through helping me navigate the vast early student records held in Special Collections or patiently listening and answering my many questions. I would also like to thank the incredibly supportive staff and student workers at Special Collections for maintaining a supportive and welcoming space for me and my fellow First-Year fellows to delve into the world of archival research. Thank you for reading my blog post and I hope that you have developed more appreciation of the rich student history of Johns Hopkins!