Please enjoy this blog post by Sophia Shoulson, PhD candidate in Jewish Languages and Literatures in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, who spent the 2024-2025 year in Technical Services in the Sheridan Libraries helping to catalog works in Hebrew and Yiddish, including many of the following works described below:

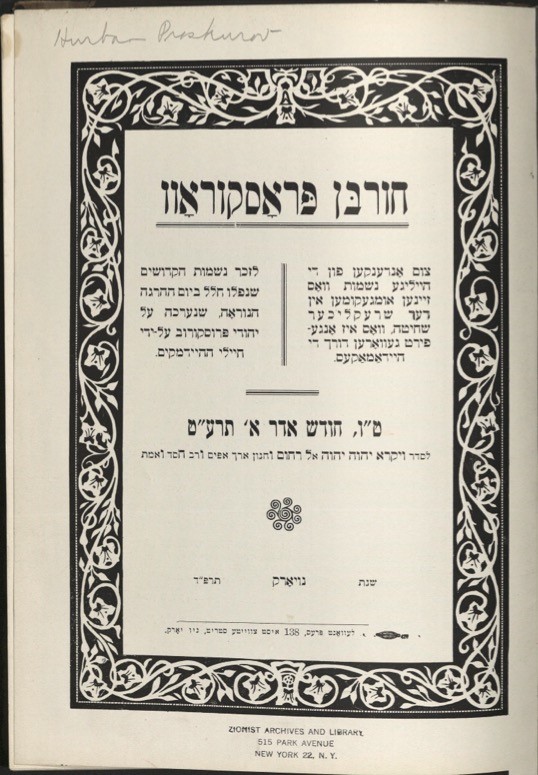

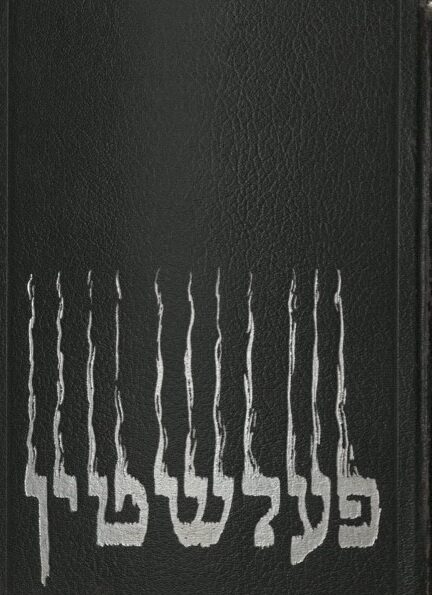

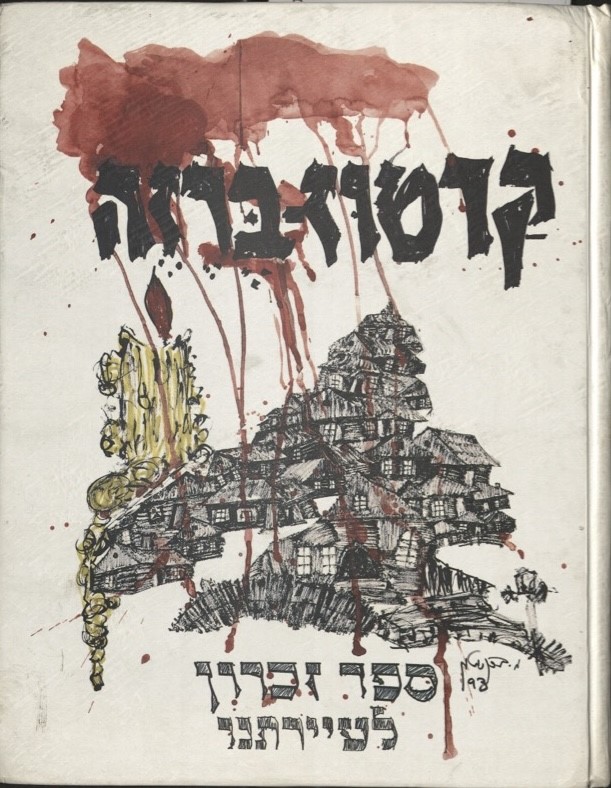

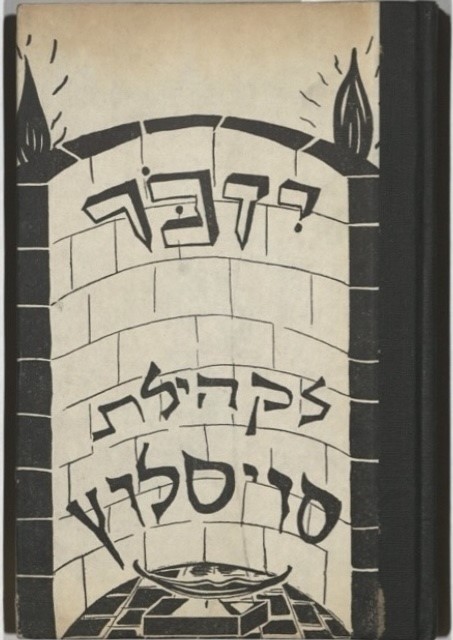

The scholar of religion Daniel Boyarin has identified the Babylonian Talmud—a record of Jewish legal discussions and rulings and the central source of Jewish religious law—as a “traveling homeland” for the Jewish people (2015). This homeland travels in the form of a text because Jewish people have lived in Diaspora, a state of global dispersion, since the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. Indeed, Jewish people, sometimes referred to as the “People of the Book,” have a millennia-long history of turning to books as both guides for cultural and religious practice, and as symbols of cultural unity: traveling, portable homelands signifying the many homelands which Jews have inhabited and left behind over the years. In the wake of the destruction of the Holocaust—the extermination of 6 million European Jews by the Nazis and their allies during the Second World War—one particular genre of book crystallized, which functions not just as a portable homeland, but also as a kind of portable memorial. These books are called Yizkor books, or yisker-bikher in Yiddish, the language in which many of them are written and in which many of the conventions of the genre developed. Figures 1-4 offer some examples of Yizkor book covers and title pages.

Yizkor books are texts—usually anthologies—which commemorate communities destroyed in acts of mass violence. They take their name from the Yizkor service, which is recited to commemorate the dead on certain Jewish holidays. Yizkor books are as crucial a component of a research library’s Judaica holdings as the study of the Holocaust is to the fields of European Jewish history and culture. In the case of the Sheridan Libraries, our developing Yizkor collection will supplement our already robust Judaica holdings.

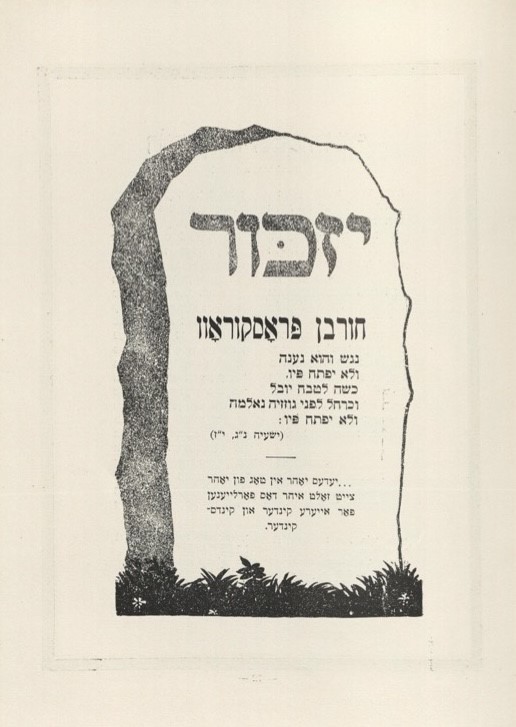

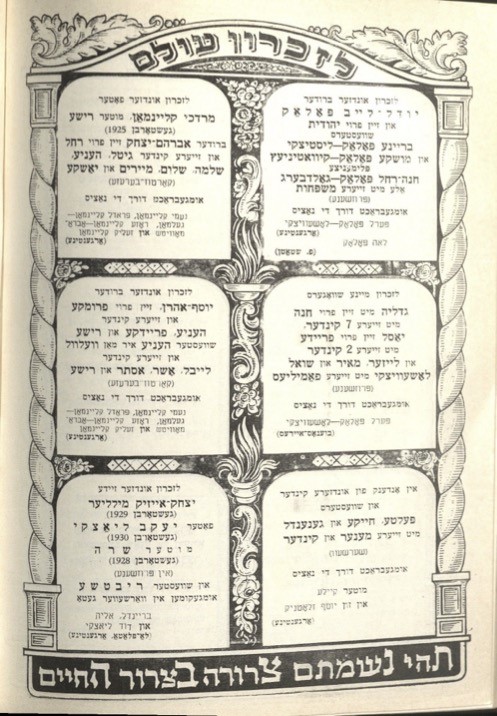

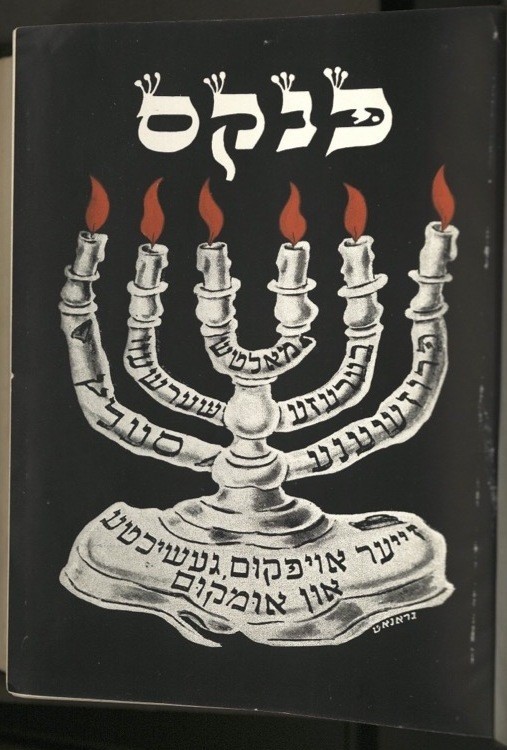

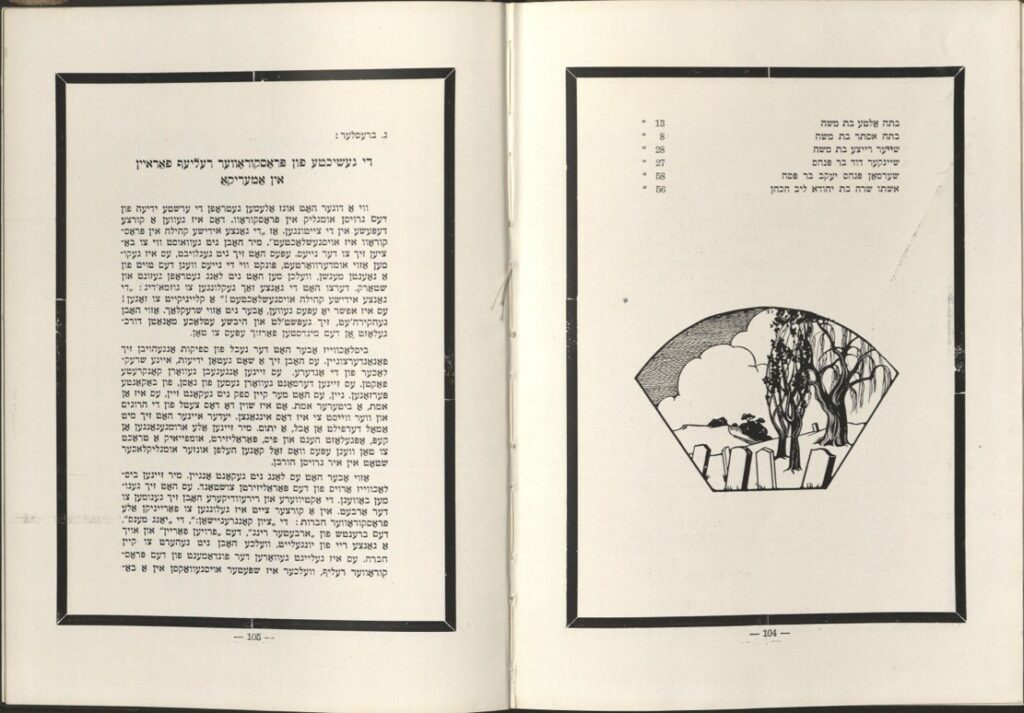

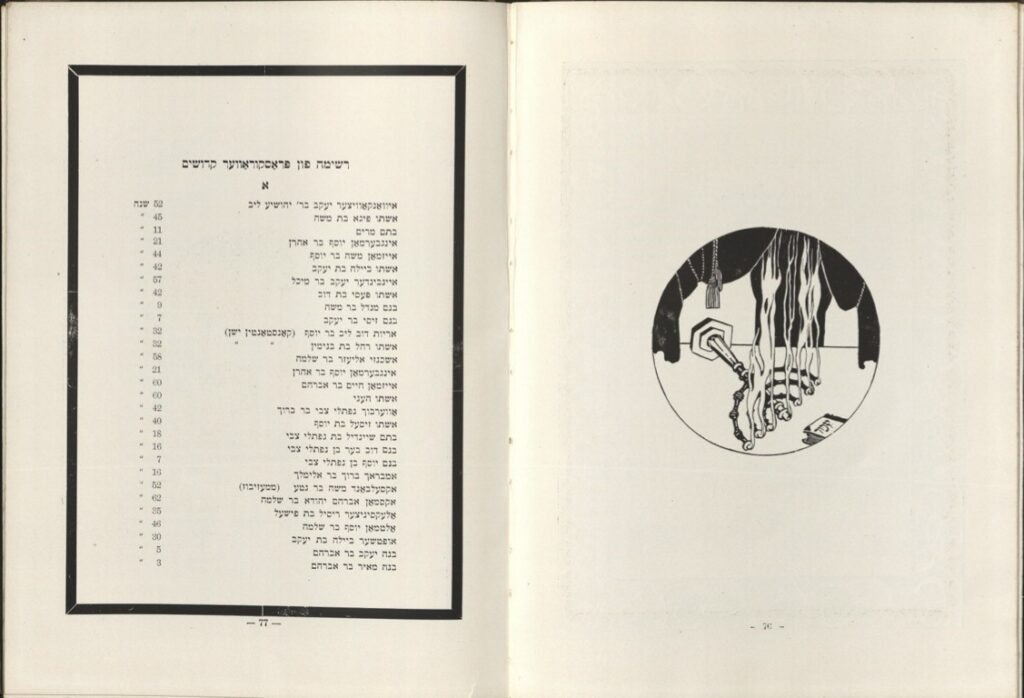

Most Yizkor books were written in Yiddish, Hebrew, or English in the wake of the Holocaust through the collective efforts of landsmanshaftn, immigrant organizations comprised of individuals originating from the same Eastern European Jewish communities. These landsmanshaftn would solicit essays as well as financial donations from their membership to facilitate the project. Often, the books deploy Jewish memorial imagery in the form of candles or even artistic renditions of tombstones (see Figures 5-7).

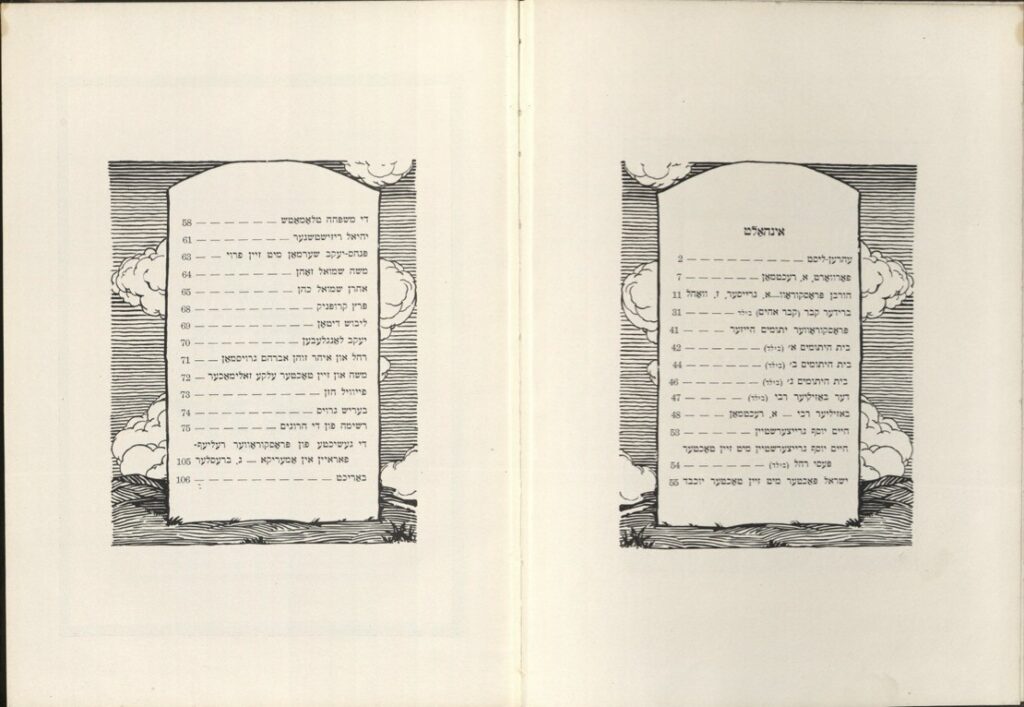

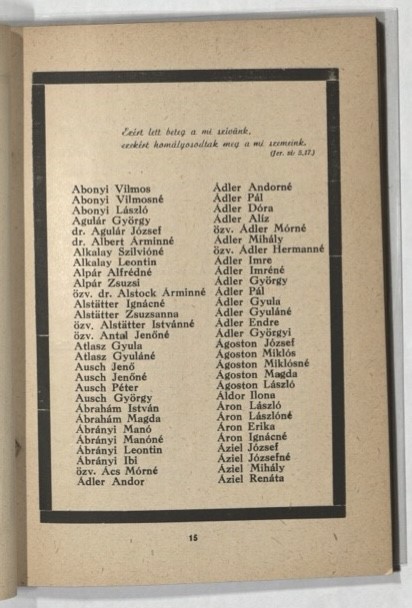

Many also follow roughly the same four-part structure: Part 1 details life in the community before the war, part 2 focuses on the community’s experiences during the war, part 3 covers the post-war period, and part 4 serves as a necrology or list of the dead (Horowitz 7-11). Note the use of memorial imagery in the necrologies featured below (Figures 8-10).

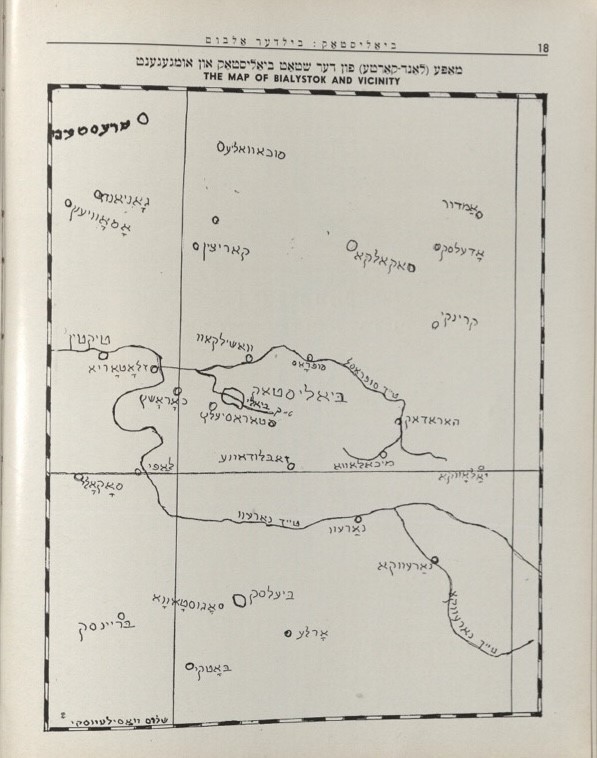

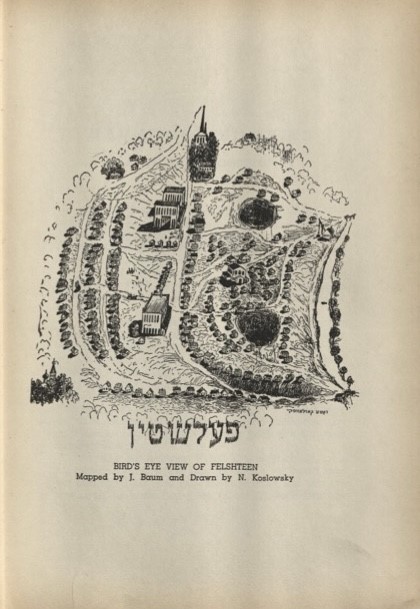

Often, the four primary sections of the Yizkor book are supplemented by a map of the destroyed community. These maps differ so greatly in both artistic style and amount of detail that some might be more accurately described as visual memories. Consider the vast stylistic differences between the maps sampled below (Figures 11-13), particularly the map of Felshtin (Figure 12), an artistic rendering designed to evoke a skull.

The narratives, rhetoric, and varied visual contents of these books speak to the complicated question of their purpose. They are at once repositories of historical information and of personal and collective memory. They are sources for scholarly use and quasi-ritualistic objects which facilitate the symbolic bearing of witness to the destruction of the Holocaust. They are, for some, the only remaining traces of family history and lost relatives.

By the strictest definition, there are approximately 400 Yizkor books, collectively produced by around 7000-8000 writers and around 1000 editors (Wein 89-90).

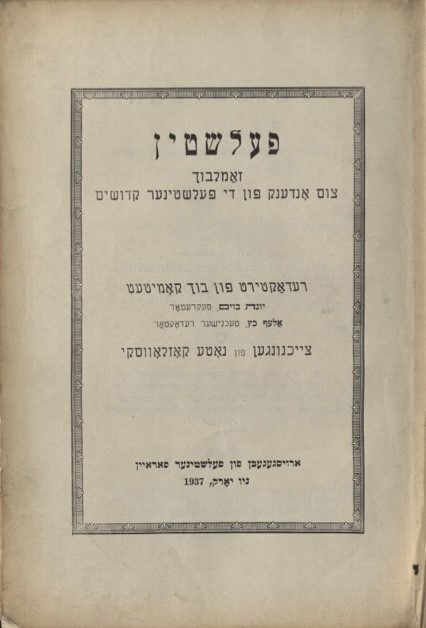

But this is where we start to get into the weeds a bit, because this strict definition, which limits Yizkor books to those produced post-war, published by landsmanshaftn, and written by multiple authors from the community, is not necessarily the most useful definition. For one thing, it excludes Yizkor books published before World War II, commemorating communities destroyed during World War I, or during the pogroms taking place in Eastern Europe around the same time. Yizkor books commemorating pogroms in Felshtin and Proskurov (see Figures 14-17 below) were published in 1937 and 1923 respectively.

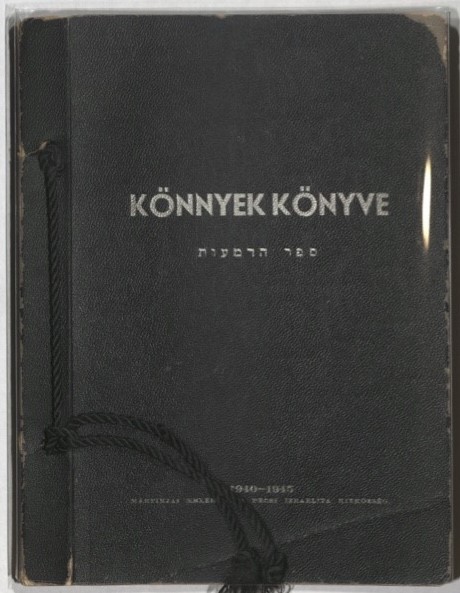

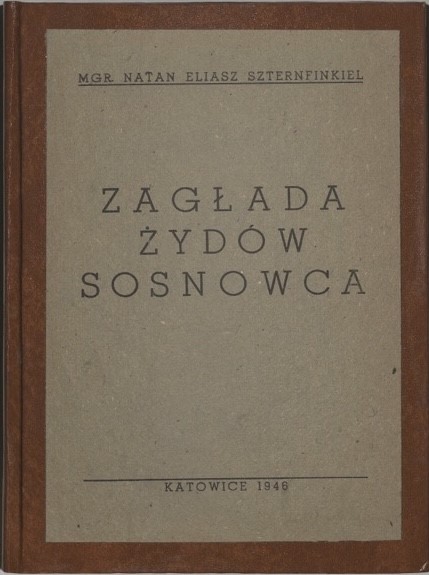

For another, this definition would exclude books not produced by landsmanshaftn, or any books produced by a single author. It also excludes texts which commemorate communities bound by something other than their hometown, and texts written in languages other than Yiddish, Hebrew, or English. For example, the Yizkor book for the community of Pécs (Figure 17) is written in Hungarian, titled Könnyek könyve: 1940-1945 mártirjai emlékére a pécsi izraelita hitközség (Book of Tears: In Memory of the Martyrs of 1940-1945 from the Jewish Community of Pécs). Meanwhile, the Yizkor book for Sosnowiec (Figure 18) is written in Polish, titled Zagłada Żydów Sosnowca (The Extermination of the Jews of Sosnowiec, 1946).

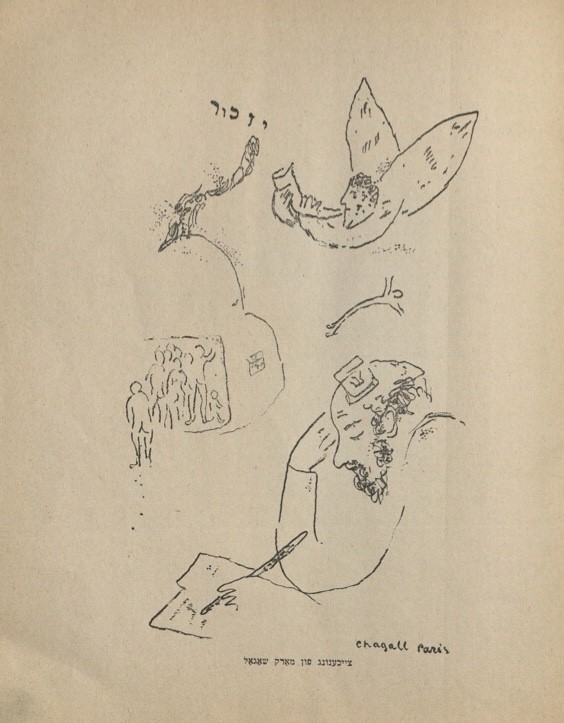

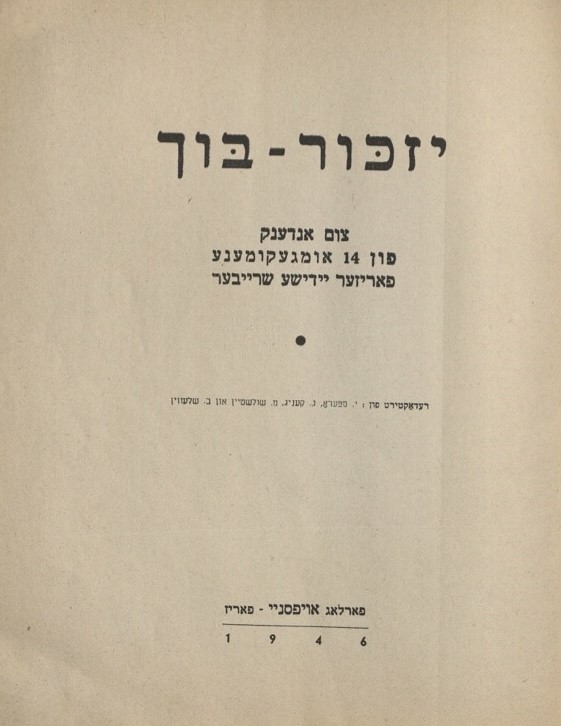

A favorite book of mine—which would be excluded according to many definitions of the genre—is the Yizker bukh: tsum ondenk fun 14 umgekumene Parizer Yidishe shrayber (Memorial book: In Memory of 14 Murdered Parisian Jewish Writers, 1946), illustrated by Marc Chagall (Figures 19-20).

This volume differs in both content and structure from the books produced by landsmanshaftn to commemorate Eastern European Jewish communities. Yet its purpose, as a source of information and as a kind of portable memorial to these authors, aligns with the broader purpose of the genre. The importance of geography is not even entirely absent from the volume: its title and contents suggest that there was once a Yiddish literary community in the French capital, and that community was destroyed.

If we start to expand the definition of the Yizkor book in these ways, the numbers get a bit unwieldy; we exchange the relatively tidy approximation of 400 volumes for a much larger and vaguer number, which can reach into the thousands. The New York Public Library, for example, lists 645 volumes in its digital Yizkor collection and about 730 in its physical holdings. Additionally, their explanation of the genre is far more descriptive than prescriptive—that is, it offers an understanding of what kind of book a Yizkor book might be, rather than what a book must be in order to be considered a Yizkor book.

The Yizkor Collection in the Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins currently contains about 259 volumes, but I hope this number will continue to grow.

Works Cited

Boyarin, Daniel. A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Horowitz, Rosemary, ed. Memorial books of Eastern European Jewry: Essays on the history and meanings of Yizker volumes. McFarland, 2014.