As we look toward spring and more time spent outside, Evergreen Museum & Library’s latest exhibition, Leave No Trace: John Work Garrett in the American Outdoors, invites us to consider the role America’s natural beauty and undeveloped spaces play in our national identity, our personal wellbeing, and our understanding of American history. On view through June 8, the exhibition documents John Work Garrett II’s many excursions into the American West during the late 19th-century, when the concept of public outdoor recreational space was taking root in the American imagination.

Curated by Michelle Fitzgerald, Curator of Collections for the Johns Hopkins University Museums, the exhibition incorporates 79 objects, pulled from collections at Evergreen, Chesney Medical Archives, the Natural History Society of Maryland, the Sheridan Libraries Department of Special Collections, and a private donor.

Born into a wealthy Baltimore family in 1872, John Work Garrett II grew up spending summers at Evergreen alongside his two brothers, Horatio and Robert, and eventually inherited the estate in 1920, using it as his primary residence until his death in 1942. Though he is best known today as a diplomat and book collector, he was also a dedicated student of natural history, with an especially keen interest in birds. He spent his life acquiring books, fossils, photography, specimens, and other materials that speak to his interest in natural history and the American outdoors.

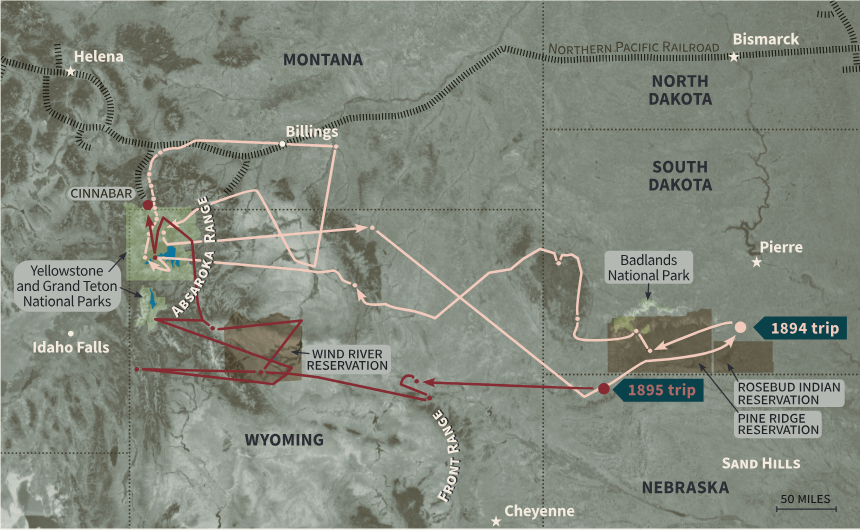

But his interest was more than academic. Despite a childhood injury that made walking difficult, Garrett pursued outdoor experiences. In 1894 and 1895, while an undergrad at Princeton University, he joined the Princeton Geological Society on its summer research expeditions out West, acting as the team’s ornithologist. On these trips he became an early visitor to Yellowstone National Park, interacted with Native American tribes such as the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho, documented his experiences in diaries and photographs, and collected mineral samples, fossils, and animal specimens for further study.

It is this collection that first inspired Fitzgerald to mount the exhibition.

“For John Work Garrett, his natural history collection and the national parks he explored were forms of art. That resonated with me when conducting research,” she explains. “The candid and beautiful images he saved from his 1894 and 1895 expeditions to Yellowstone provide a personal perspective that I think many present-day visitors can empathize with.”

At the time of Garrett’s visit to Yellowstone, the park received only about 3,000 documented tourists annually; Now it gets over 3 million.

At the time of Garrett’s visit to Yellowstone, the park received only about 3,000 documented tourists annually; Now it gets over 3 million.

This increased tourism has changed many things about the park, but Garrett’s collection captures intimate moments of wildlife and landscapes at their least disturbed, lending a wistful poignancy to the images.

“Today, national parks have become valuable yet threatened places of retreat for many people and it’s more important than ever that we consider them as part of our natural as well as our cultural heritage,” says Fitzgerald.

Still, Fitzgerald cautions against viewing the past through rose-colored glasses. “While there’s no doubt that John Work Garrett’s love of the American West was genuine, we can’t ignore that he was part of a movement that brought additional attention to these wild spaces, ironically making them more vulnerable to development, overuse, and exploitation.”

There is also the question of just how “wild” the spaces were to begin with. According to a still extant (as of February 25, 2025) National Park Service page, “For thousands of years before Yellowstone became a national park, it was a place where people hunted, fished, gathered plants, quarried obsidian, and used the thermal waters for religious and medicinal purposes. . . . Tribal oral histories indicate more extensive use of the area during the Little Ice Age. Kiowa stories place their ancestors here from around 1400 to 1700 CE. Ancestors to contemporary Blackfeet, Cayuse, Coeur d’Alene Nez, Shoshone, and Perce, among others, continued to travel the park on the already established trails.”

The exhibition incorporates objects that speak to the way white settler culture paradoxically erased and fetishized Native culture. Fitzgerald had help from two Krieger students—Elana Neher (KSAS ’20) and Morgan Brown (KSAS ’24)—in researching the Native-related objects.

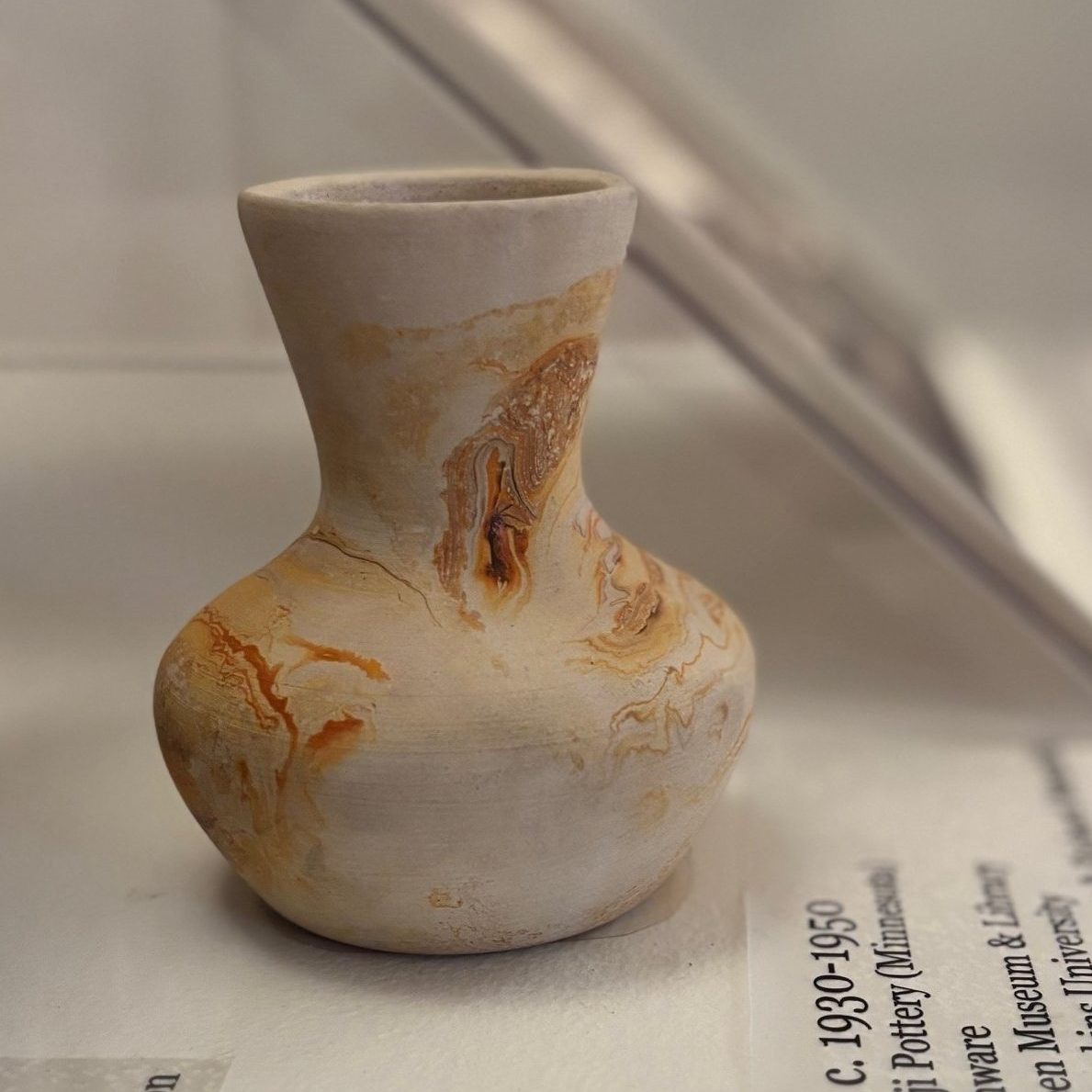

Brown, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and descendant of the Choctaw people, examined a vase made by the Nemadji Pottery company of Minnesota.

“They fabricated their pieces from what they imagined Indigenous pottery looked like, marketed them as ‘Indian-inspired,’ and sold them in droves to settlers,” Brown writes in the exhibition. “Attempts like this to replicate Indigenous art were not uncommon in John Work Garrett’s lifetime. When examined, they can reveal a trend of cultural appropriation through ceramics and imitation commodities.”

Neher, now pursuing a master’s degree at the Bard Graduate Center, similarly found objects in Evergreen’s collection that were made to look like they had been created by Native artists but in fact were more likely the product of a Euro-American craftsperson.

“Elana re-examined a leather portiere, once cataloged as a ‘tipi liner,’ and her research raised questions about its origins,” Fitzgerald notes. “Subsequent consultations determined that the piece was most likely created by a Euro-American craftsperson who adopted styles from Lakota buffalo robes, intentionally making ‘primitive-looking’ design choices to align with the settler ‘vision’ of Native people, rather than actual Native craftsmanship, which was and is sophisticated.”

As Fitzgerald shared in a Lunch with the Libraries & Museums talk prior to the exhibition’s opening, Leave No Trace took four years from conception to installation, and could not have happened without generous support from donors, in addition to university funding.

Private donations further all aspects of exhibition creation from student experiences in the museums to preparing sensitive objects for display and exhibition design and programming.

“That we even have these materials to interpret 130 years later is due to a significant act of philanthropy,” she says. (John Work Garrett II left Evergreen and most of his collections to the Johns Hopkins University upon his death.)

Supporting the Johns Hopkins University Museums’ Exhibitions Fund allows donors to directly impact the preservation of cultural heritage, enabling the creation of exhibitions and programs that inspire future generations to appreciate and protect the natural and historical treasures that define our world.

To give a gift to the JHU Museums’ Exhibitions Fund, click here.