Please enjoy this post from Tabb Center Public Humanities Fellow Hoesy Corona.

Initiatives like the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center’s Public Humanities Fellowship invite artists, cultural workers, and knowledge makers to step into the world of archives and use our arts-based research skills to creatively hold a mirror to the collection in new and unexpected ways. This work is imperative to the continued expansion of knowledge building: artists can assist institutions in developing a more inclusive reframing of the historical record that expands upon who we really are.

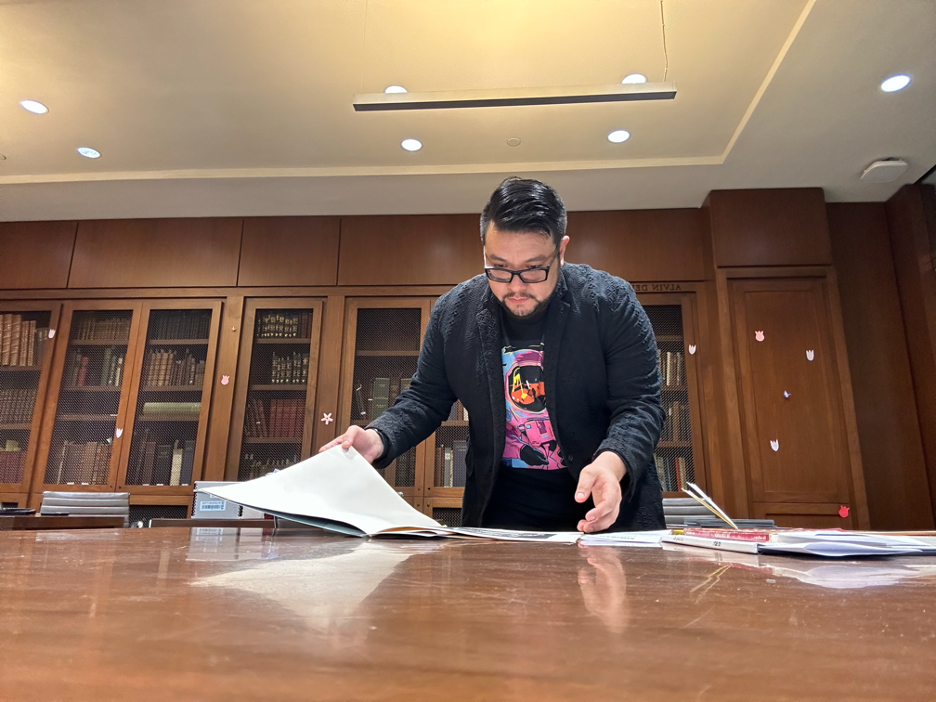

I first visited Special Collections at Johns Hopkins University in November 2022, after I was selected as the Tabb Center’s inaugural Public Humanities Fellow. I was eager to find inspiration in documents relating to U.S. based Latinx people with the hope of informing a new set of audio-based interviews and visual artworks. However, upon a more-in depth search I learned that there was no designated repository for the preservation of Latinx history at Johns Hopkins. I often saw the phrases “ITEM NOT FOUND” and “NO RESULTS” when searching the digital library catalogues. I knew that my ancestors and other relations had deep roots in this country’s land and therefore were certainly indelible to the fabric of the country. So where were my forefathers and foremothers? Where are my intellectual guides? Where were my people? I chose to sit in the omission. In the dark vastness.

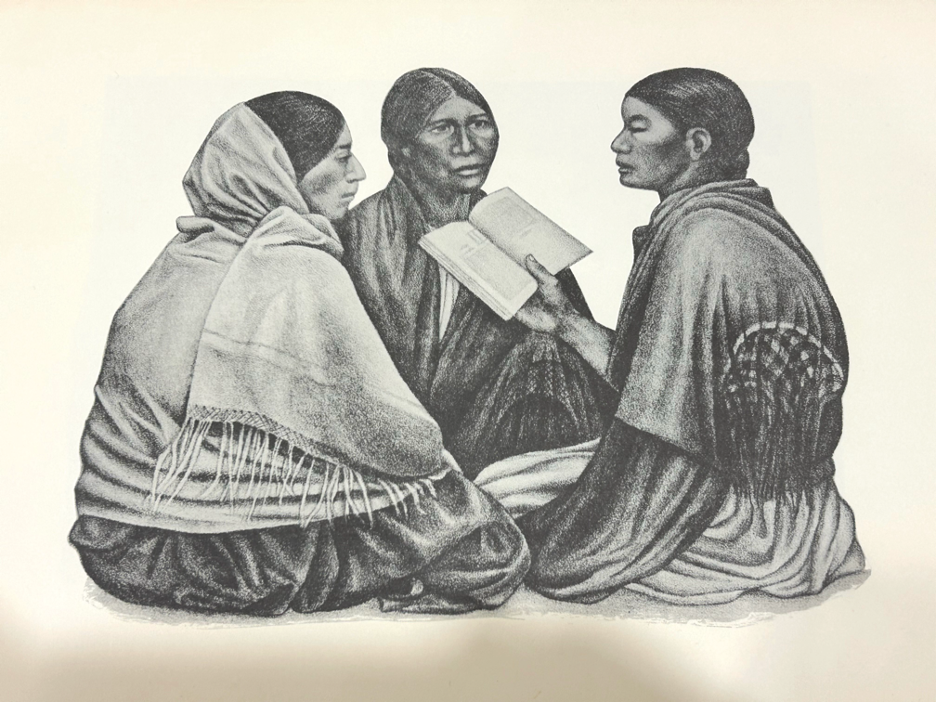

It was then that I reluctantly sought out the book titled Prints: Mexican which featured the graphic works of Mexican artists. One of those artworks, titled “La Lección” (the lesson), is a striking image by Elizabeth Catlett Mora which depicts a group of three indigenous Mexican women seated on the floor wearing rebozos (shawls) while one reads from a book and the other two listen closely. All three women are set against a white background. This image proved to be a powerful one that would guide me through the unlit path ahead. Here was the perfect encapsulation of what I was experiencing: the blank white background represented an archival deficit. The woman reading from the book was a stand-in for our perseverance—our oral histories—and the indelible sense of belonging and caring for each other despite the constant weaponized erasure of our lived experiences. The two attentive women were stand-ins for the embodied and shared knowledge of current and future generations. I could almost hear las señoras saying “we lived. we were here. our stories are with us and they will continue to circulate even against the threat of a stark white background.”

“La Lección” inspired the establishment of an experimental social sculpture titled The Latinx Art Culture and Memory Archive (TLACMA): a Latinx repository within Special Collections that claims shelf space for the discoverability, preservation, and study of Latinx Histories. Open to the public, the TLACMA doubles as a call to action for institutional leaders, funders, and archivists to center the continued acquisition, preservation, and study of U.S. Latinx contributions to the historical record. Through trust-building and by making deliberate invitations to scholars, artists, researchers, and the general public to make relevant contributions to Special Collections related to Latinx history in the United States (including documents, papers, texts, books, photos, videos, oral histories, new media, memories, and more) it is possible to get one step closer to fulfilling the core and radical idea of the archive.

The TLACMA collection was inaugurated in 2024 with a set of 12 museum boxes containing 12 unique books, paper documents, and 11 audio interviews documenting the contributions of contemporary U.S. based Latinx artists, curators, and scholars with ties to Baltimore and Washington DC. The TLACMAis also a physical steel sculpture in the form of a red circulation library cart. The red color emits a sense of urgency while the circulation cart evokes an active library providing outreach beyond the stacks. The sculpture functions as a physical and symbolic representation of the longing for a comprehensive collection of Latinx histories. Finally, the cart contains a series of new collages that fill the void in Elizabeth Catlett’s original graphic work. In the collages the three women share knowledge in a room full of empty shelves, against a sunset, in nature, and finally next to the incomplete TLACMA collection waiting to be filled. The collection is archived by Special Collections and open to the public.

The TLACMA Circulation Cart also performs as a pop-up archive. It was on view at Baltimore’s Creative Alliance in February 2024 and the Enoch Pratt Free Central Library, from April through May 2024. Each pop-up promotes the TLACMA collection and the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center, inviting the public to preview and handle books and documents from the collection.