By Jenelle Clark and Hanjie Guo

Processing archivists spend a lot of our time crafting careful description for the collections our institutions hold. For items that our curators purchase for our collections, that means taking a critical look at the dealer description as we write our own description for those materials. We ask ourselves, is it accurate? Is there a more complete story that we need to share with our users? One recently acquired photo album proved to be an unusual case, as we found ourselves questioning existing assumptions around these photos from post-WWII Nagasaki.

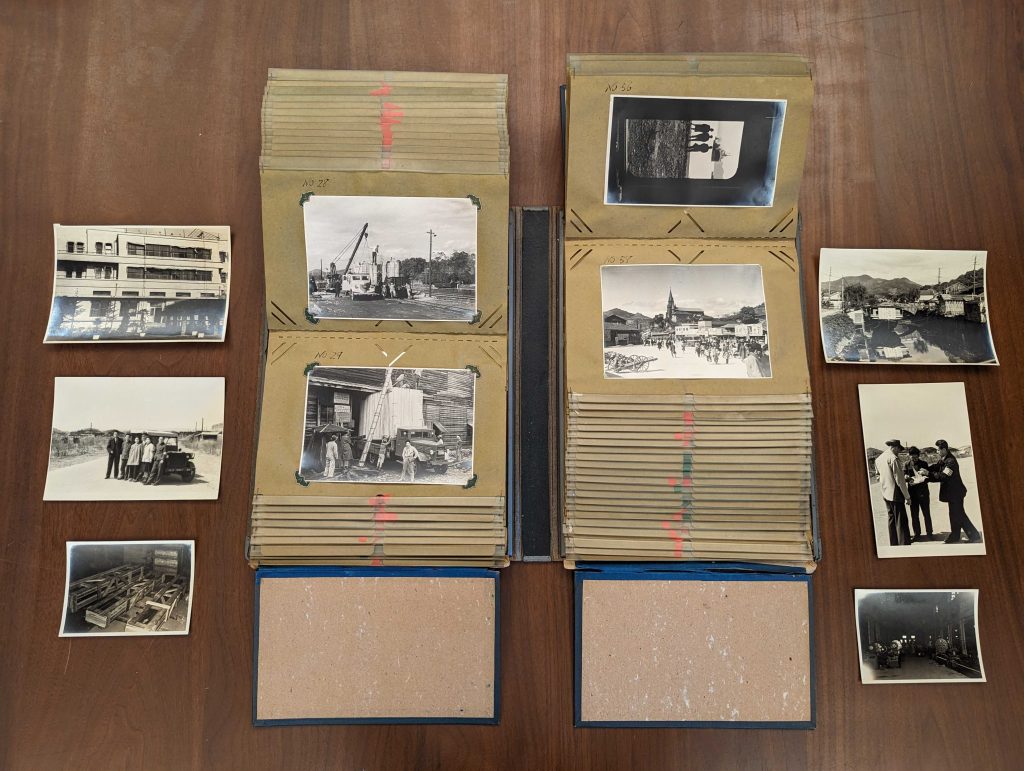

Jenelle Clark is the library’s accessioning archivist, in charge of documenting and occasionally processing new manuscript collections and university records when the Special Collections and University Archives department receives them. When Jenelle began work on this Japanese photo album, described by the dealer as an “official photo album documenting cleanup in Japan after World War II,” she knew she wasn’t properly equipped to describe it herself.

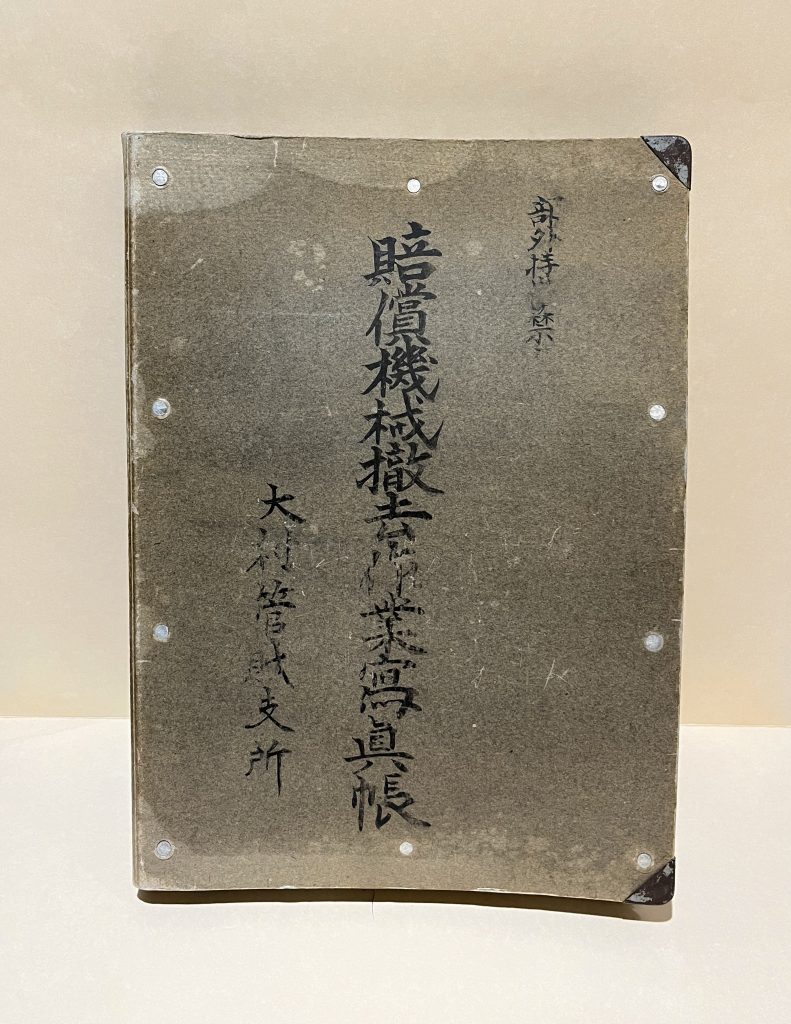

She could identify the characters on the album’s cover as Japanese Kanji, but she couldn’t read them, and an attempt at using Google Translate to get a rough translation failed when several characters proved to be too worn for Google Translate to detect. All she had was the baffling dealer translation, “Compensation Machine Removal Work Photo Book / Trust Omura Branch, Omura Area,” and a description of the album that claimed the photos “seem principally to have addressed the reconstruction of port facilities, factories, warehouses, and railroad lines destroyed during the war,” as shipping crates full of industrial equipment “from a number of far-flung origins” were moved by workers from ships to warehouses.

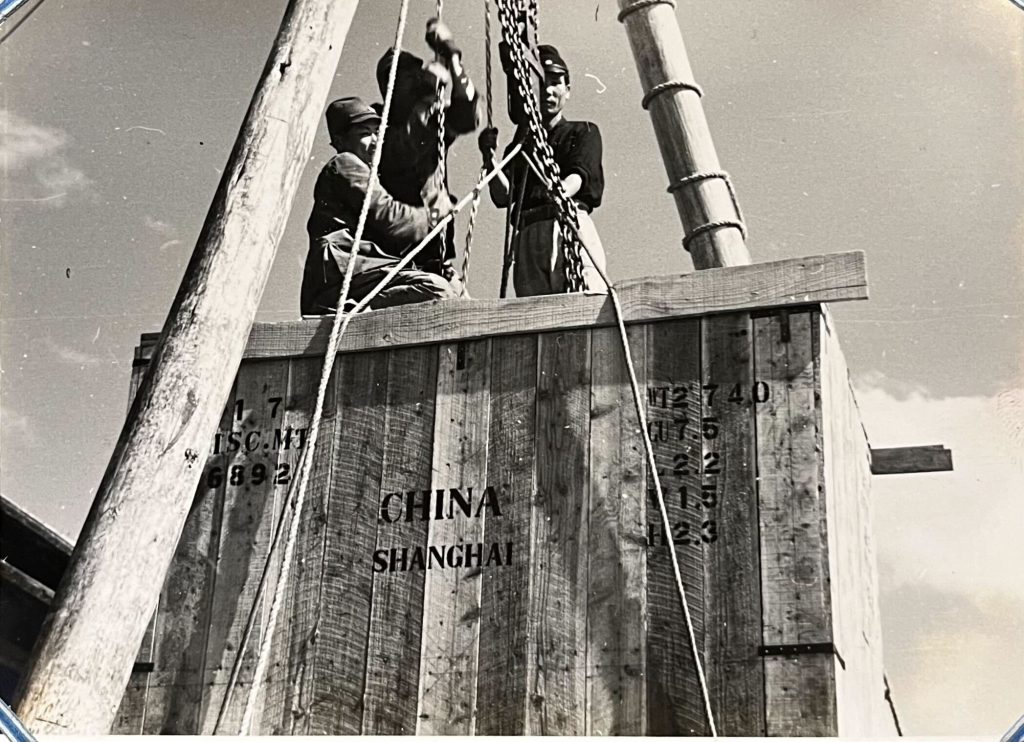

Examining the photos, Jenelle did see shipping crates of industrial equipment marked with several different locations in the Pacific, as well as workers moving these crates between warehouses and ships. So far, so good. Still, it was an odd set of photos. “Compensation Machine Removal Work” was a confusing set of words to be attached to a cleanup and reconstruction project. If these images were meant to show cleanup and reconstruction work, one might imagine scenes of scaffolding and buildings, rather than an emphasis on shipping crates. Upon being shown the album, one colleague remarked that the photos seemed “oddly quiet.”

After querying her colleagues to find out who might have the necessary language expertise, Jenelle reached out to Hanjie Guo, a student employee in Special Collections, for help identifying the Kanji characters and translating the cover text. Similarly puzzled by the translated English title, Hanjie considered the grammar in it, wondering if there is such a thing as “compensation machine.” She then dug deep into the translation work to find a more informative translation for some of the phrases. Searching the album’s title using the dealer translation, “Compensation Machine Removal Work,” produced irrelevant results regardless of how she modified the search terms, a problem that Jenelle had also experienced.

After studying the album, Hanjie decided to search in Chinese, since one of the photos showed “Shanghai” on a shipping crate. This search met with success. Hanjie came across an article titled “Japan’s Reparations Material for China and Its Post-War Economic Reconstruction Policy: A Case Study of Central Shipbuilding Company,” written by Mingli Hsiao and published by Academia Historica (Taiwan). The article focused on Japan’s transfer of shipbuilding equipment to China after the war, providing valuable historical context and introducing Hanjie to the term “reparations.” With this new understanding, Hanjie found other relevant articles on JSTOR that helped her confirm that this was indeed an accurate term for the activities depicted in the album.

Hanjie shared her new translations with Jenelle, suggesting that a better word for “compensation” was actually “reparations.” She also showed Jenelle several articles on the Japanese reparations program in which the Allied powers required Japan to pay reparations for war damages, including the transfer of industrial equipment via the Far Eastern Commission to China, the UK, the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines.

It was a lightbulb moment for Jenelle, who realized that the photos were not depicting relief efforts and reconstruction in Nagasaki, but rather the dismantling of its industrial base to satisfy reparations requirements. Suddenly, the order of the photographs made sense, with the warehouses shown early in the album and the ships shown at the end. The countries on the crates matched those that the Far Eastern Commission had designated as the beneficiaries of this massive industrial equipment transfer program. The depicted transportation of equipment was not incidental to some wider project, in some strangely myopic photo series, but rather the project itself.

In this job, we study historical materials for clues that answer questions of where, why, and when. It’s a job filled with the joy of working intimately with historical artifacts. It’s also a highly collaborative process, as we consult our colleagues with language and subject expertise so we can be sure that our understanding of the materials isn’t flawed. We work hard to be accurate because any flawed assumptions we make in our description can carry over to researchers’ approach to those materials. It was gratifying to solve this translation puzzle, because now our description places the photos within their true historical context. In this case, it’s an emotionally complex historical context; one can look at these photos knowing what Japan did during the war to these countries to whom they made reparations, while also recognizing that these reparations activities took place in Nagasaki within only a couple of years after it was bombed. Now it’s up to our researchers to delve deeper into the nuances of that history, but the work we’ve done makes sure we won’t be leading them down the wrong path.