Enjoy this post by Amy Li, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2022-2023 academic year!

Welcome to my first blog post! My name is Amy Li, and I am a freshman majoring Public Health Studies and Economics. As a Freshman Fellow, I am exploring the Hopkins student life archives under the mentorship of Katie Carey.

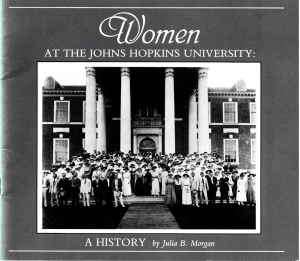

Through Special Collections, I learned that Hopkins started admitting women as undergraduates nearly fifty years ago. I began researching the coeducation because of Julia B. Morgan’s 1986 Women at the Johns Hopkins University: A History, introduced to me by my knowledgeable and incredible mentor, Katie. Morgan was Hopkins’ first University Archivist, and I was intrigued by how she presented the role of women in the Hopkins community since 1877. This year was when Martha Carey Thomas and Emily Nunn were the first women to try to apply to the university (a year after Hopkins’ establishment). They also ignited the idea of coeducation for years to come.

As I navigated through the Sheridan Libraries Archives, I was captivated by the deep consideration and effort of university officials, faculty, and students to transform coeducation from a concept into a reality by Fall 1970. I explored the correspondences of university Presidents, ranging from Presidents Daniel Coit Gilman to Lincoln Gordon, and the papers from faculty and students. Gradually, I realized that coeducation was not a sudden concept due to the modern movement for women’s rights. Rather, it was a topic that was often debated since the university’s founding.

Through Morgan’s research regarding the early debate of coeducation, I learned how President Gilman sought the advice of other university presidents to ultimately not admit women as full-time Hopkins students when establishing the university. From the guidance of Presidents Charles William Eliot of Harvard and James Burrill Angell of Michigan, President Gilman reasoned how coeducation would lead to undesirable outcomes as women would confront “rougher influences” in university. He still encouraged the establishment of a women’s college—Girton College for Women—that was never formed. Nevertheless, this lack of coeducation did not deter women from seeking an education at Hopkins. While Thomas and Nunn tried to join a degree program, other pioneering women include Christine Ladd-Franklin (the first woman in the Hopkins Faculty of Philosophy), Florence Bascom (the first woman awarded a Hopkins Ph.D.), and Florence Bamberger (the first woman to be appointed a full Hopkins professor).

While many women sought education at Hopkins, it was not until the late 1970s when Hopkins started to reconsider their decision. This shift was primarily due to the influence of other undergraduate institutions, notably the Ivy League, becoming coeducational.

In 1969, Gordon formed the Task Force Committee on Coeducation, consisting of two members of the faculty, two undergraduate students, and one representative each from the Office of the Dean and the Office of the Vice President for Administration. According to a report from the Committee on Coeducation, Hopkins’ movement towards coeducation was to enhance the intellectual atmosphere and motivation by diversifying the natural science-leaning community and seeking a more liberal education (reminder that this was 1969). The committee cited a Princeton analysis on how women are more likely to expand the student field of study to include more humanities. Especially when most of the applicants who responded and denied admission to matriculate to the coeducational Ivy League (except Dartmouth), they believed that their response to changing the social conditions would allow Hopkins to continue to be comparable to its Ivy League competition. Despite these goals, the committee faced debates regarding number of women admitted, housing arrangements, athletic program adjustments, budgeting, advising, counseling, and health services, and overall legacy for Hopkins to become coeducational.

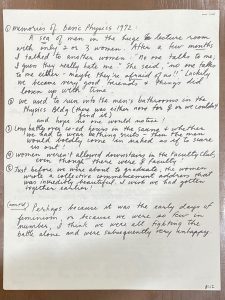

By Spring 1970, there were a few Baltimore students who entered the university early, and by Fall 1970, ninety women (twenty-one freshman and sixty-nine transfer students) matriculated to Hopkins as full-time undergraduate students. While the students faced issues regarding housing and treatment by male students, they spearheaded significant change at the university by collaborating to enhance their quality of life. Gradually, the undergraduate women enrollment and overall female representation on campus increased, ultimately allowing Hopkins to embrace its fully coeducational community.

I plan to focus on four primary areas of student life: (1) student housing and facilities, (2) athletics and Title IX, (3) women’s health, and (4) women of color. Because of the influence of other universities on Hopkins’ coeducation, I hope to compare the efforts of coeducation at different universities with those of Hopkins by reaching out to other universities for their coeducation documents. I intend to collaborate with Hopkins archivists to gain their perspective regarding coeducation and create an online library archive. I seek to understand the social conditions of the United States that led to this dramatic change and the goal of the coeducation movement of American universities during the mid-twentieth century.