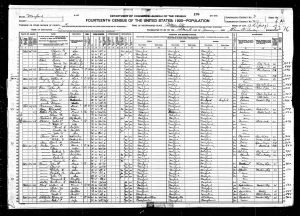

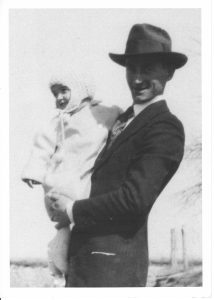

On March 28, 1923, my great-grandfather, John Edgar Shilling, died on the Homewood campus at age thirty-three. He was not employed by the university, nor was he a student. According to the 1910 census, the first of his adult life, he rented a room on Merryman Avenue, now 40th Street, with his new wife and baby girl, next door to his in-laws.[1] He worked as a street paver. By 1917, he was promoted to the job of foreman at Baltimore Asphalt Block and Tile Company. He supported his wife and two children, on which basis he claimed exemption from the draft (WWI).[2] He had also moved to Elm Avenue. According to the 1920 census, the last of his adult life, he rented a townhouse on Elm Avenue with his wife, three children, including my eight-month-old grandfather, mother-in-law, brother-in-law, and a boarder. He was still employed as a foreman in street work.

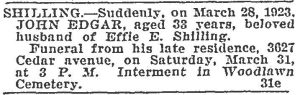

Three years later, his obituary in The Baltimore Sun read: “SHILLING – Suddenly, on March 28, 1923, JOHN EDGAR, aged 33 years, beloved husband of Effie E. Shilling. Funeral from his late residence: 3627 Cedar avenue….” By 1923, he and Effie had moved again to Cedar Avenue, now Keswick Road, possibly to accommodate their fourth child.

How did he die? A few years ago, I was told by a relative that he fell off the roof of Gilman Hall. We believed that he died in a roofing accident, but the construction of Gilman Hall was completed in 1915. What was he doing on the roof in 1923?

I requested a copy of his death certificate from the Maryland State Archives.[3] Death certificates contain a wealth of information for historical and genealogical research. In 1923, a death certificate issued by the health department of the city of Baltimore listed the place of death; the address, sex, race, marital status, date of birth, age, occupation, and birthplace of the deceased; the names and birthplaces of both parents; the date and cause of death; and the date and place of burial. By 1923, John had become the Manager of the Roofing Department at Pen-Mar Company. He died, or was pronounced dead, at Homewood Hospital on North Charles Street.[4] The cause of death is listed as “fracture of skull due to a falling plank accident.”

What kind of work did Pen-Mar, a construction and building supply company, do on the Johns Hopkins campus? Court records from the workers’ compensation suit brought by my great-grandmother, Effie Shilling, describe his role in the construction of a dormitory and preserve remarkable eyewitness accounts of his death.[5] According to records from the Superior Court of Baltimore City and the Maryland Court of Appeals, Pen-Mar was subcontracted to construct the slate roof of the Johns Hopkins University dormitory by Frainie Brothers and Haigley, general contractors. Clough and Molloy, another subcontractor, was responsible for the stone work. At 11:00am on March 28, 1923, employees of Clough and Molloy began the work of extending a scaffold on the south side of the building in order to place a capstone on the southwest chimney. Witnesses from Pen-Mar identify three men in the area of the scaffold and roof. Just prior to the accident, with the help of two men on the ground, they were pulling up four by fours with a three-quarter inch rope and laying them on the scaffold and on the eaves. One of the witnesses, Mr. Schmick, recalls the rope hanging down and one man mounting uprights when he left the south side of the building, three or four minutes before the accident. Around 2:30pm, the foreman of Pen-Mar, my great-grandfather, was walking along a pathway to the south of the scaffold, when a piece of scantling, 4 by 4 by 10, fell from above.

An employee of Pen-Mar, Mr. McGregor, testifies: “I saw him walking toward me, and when I looked again I saw him holding his head, and then he fell over, and I saw this gentleman come down. I saw a four by four, ten feet long, laying alongside him, with blood on it. The man on the scaffold came right down to us and said, ‘Oh, Mac, oh my God, I wish it was me!’”

Another employee of Pen-Mar, Mr. Wilson, was walking 25 or 30 feet ahead of his foreman: “As I walked to where Guy and McGregor were making brackets, something attracted my attention, and I turned around and saw Mr. Shilling lying on the ground. We ran over. I picked up his head, Guy mopped his head where it was cut and bleeding, and McGregor ran to the telephone. I did not see the piece of timber hit him, but did see a piece of 4 by 4, between 10 and 12 feet long, laying on the side of him, with blood on the edge. When I walked around the building just ahead of Mr. Shilling, I did not see any scantling…on the ground.”

Shortly after his death, Effie and her children, ages 13, 10, 3, and 10 months, were granted $5,000 plus $125 in funeral expenses from Pen-Mar and the Indemnity Insurance Company of North America. Two months later, Effie sued Clough and Molloy, Inc. under section 58 of the Workmen’s Compensation Act. Less than a decade earlier in 1914, the first comprehensive workers’ compensation law was passed in the state of Maryland, allowing her to file suit as a dependent of a deceased employee against a third party. On February 16, 1925, almost two years after John’s death, the Superior Court of Baltimore City found the defendant negligent and liable. Effie recouped $5,125 for the insurance company and $9,875 for her family. Clough and Molloy appealed the verdict and lost.

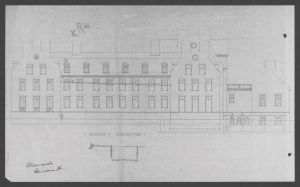

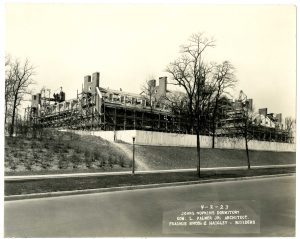

Gilman Hall is not and was never a dormitory. In November 1922, the Johns Hopkins University Circular, or Annual Report of the President, records the construction of the Alumni Memorial Dormitory, now AMR-1, the first dormitory on campus: “Building construction was started in August and has proceeded rapidly, and it is expected that the building will be ready for occupancy in the Summer of 1923.”[6] Included in the Superior Court records is a drawing of the south elevation of the dormitory with Xs marking the southwest chimney, the work on the scaffold, and the site of the accident.

This short article is dedicated to the memory of my great-grandparents, John Edgar and Effie Elizabeth (Barnes) Shilling, my grandfather, John Walter Shilling, and his three sisters: Ruth, Dorothy, and Edith.

[1] “United States Census, 1910,” online database, FamilySearch, Maryland, Baltimore City, Ward 13, ED218, image 12 of 16, citing NARA microfilm T624 (Washington, DC, National Archives and Records Administration).

[2] “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918,” online database, FamilySearch, Maryland, Baltimore City, no. 13, G–Z, image 3422 of 4648, citing NARA microfilm M1509 (Washington, DC, National Archives and Records Administration).

[3] BALTIMORE CITY HEALTH DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF VITAL STATISTICS (Death Record), Certificate No. D74308, John Edgar Shilling, Date: 03/28/1923 [CM1132-151]. Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.

[4] Located at 2724 North Charles Street, Homewood Hospital preceded the North Charles Hospital, which was acquired by the university in 1986, renamed the Homewood Hospital Center–South, and closed in 1991.

[5] BALTIMORE CITY SUPERIOR COURT (Civil Papers) Effie Shilling et al. vs. Clough and Molloy, Inc., 1924, No. 2390 [MSA T583-552]. The original case was decided in favor of the plaintiff on February 16, 1925. Maryland Court of Appeals, Clough and Molloy, Inc. v. Effie Shilling, Dec. 4, 1925, in Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Maryland, vol. 149, 1926, pp. 189-207. The decision is summarized in the Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, no. 444: Decisions of Courts and Opinions Affecting Labor 1926, June 1927, pp. 234-5.

[6] The Johns Hopkins University Circular: Report of the President of the University 1921-1922, vol. 41, no. 341 (November 1922), pp. 5-6.