Enjoy this post by Julia Mendes Queiroz, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2021-2022 academic year!

Hello, library blog readers! Whether you are a cartography connoisseur, interested in studies on the Caribbean islands or clicked on this post by accident, welcome! My name is Julia Mendes Queiroz, and I am a first-year student from Rio de Janeiro, hoping to major in Economics and International Studies. I am also extremely grateful to be one of the Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2021-2022 academic year, working on the project “Reading between the Rhumb Lines: Mapping the Caribbean”.

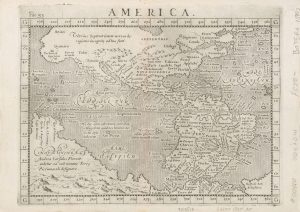

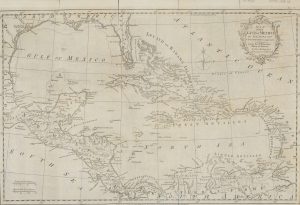

Through the project, I have had access to some truly incredible antique maps, some of them stretching back to the 16th century, like this 1595 map of the Americas.

There are several interesting tidbits of information that can be extracted from this map. First, the depiction of South America is almost comically erroneous to the eye of the modern, Google maps-using citizen. Shown as an oval-esque shape, there are some features that are very intriguing, such as the gigantic river estuary called “Rio de la Plata,” that drains the Uruguay and Panama rivers into the Atlantic, being drawn about five times larger than it actually is, and about 3,500 kilometers north of its actual location. Furthermore, an entire region of the continent is simply labeled as Ins. [Insula] Trinitatis Metatifera; the first part, Ins. Trinatis, translates to Trinity Island. After scouring countless historical archives, the best interpretation for metatifera I have come up with is that it refers to water and thirst. While this area is currently extremely hot and arid, it was once a tropical rainforest, which may have contained valuable water sources. It could also be referring to a tributary of the Amazon River. And, for my readers from the sunshine state, you will be happy to know that in 1595, Florida was named…. Florida.

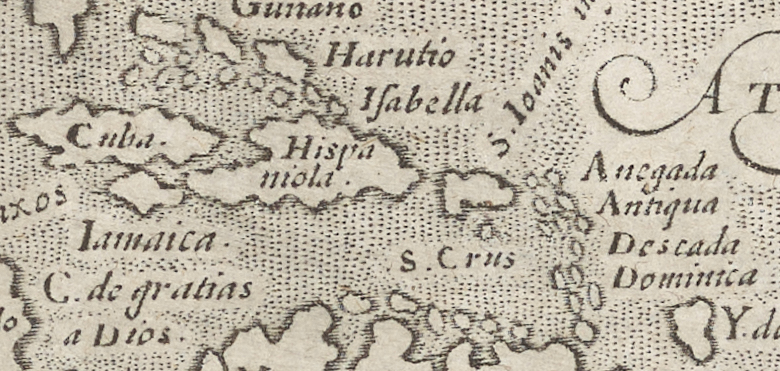

By 1595, European explorers had made landfall in most of the larger Caribbean islands, such as Montserrat, Cuba, Jamaica, Guadeloupe, and St Kitts & Nevis. These are usually depicted in even the earliest renditions of maps of the Caribbean Ocean, though they are sometimes labelled with unique names such as “Descada”, of which there are very few records. Interestingly, we also see the religious names given to some islands, such as Puerto Rico, which was called San Ioannis, Latin for “San Juan”, after St John the Baptist.

In this same map, there are also details of European settlements and patterns of colonization in the Caribbean. In the Northern part of the Dominican Republic, known back then as Hispaniola, La Isabela, the first Spanish town in the Americas, is denoted as Isabella. There is also the Cabo de Gratias a Dios, the “Cape Thanks to God”, given its name after European boats escaped from a particularly rough storm in 1502.

However, despite the unfortunate efforts by European colonizing missions to erase the already-established cultures of the Arawaks, Tainos and Caribs, and many other peoples who originally inhabited the Caribbean, there are still visible remnants of their traditions and languages. The most famous example is of course the name Caribbean, which comes from the Caribs, one of the dominant tribes that inhabited the islands in the 15th century. Another one is the name Jamaica, which originated from the Taino word Xaymaca, meaning “the land of wood and water”, due to the island’s extensive natural resources.

In one of the later maps in the John and Linda Greene Map Collection, confectioned in 1777 by the Hydrographer for his Majesty King George III, there are other examples of indigenous culture being kept alive by tribes resisting European brutality.

In the figure above, showing Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic), the cacicazgos (provinces ruled by a cacique, an indigenous chief) are demarcated, such as Xaragua, named for its cacique, and Guarionex, meaning the “the brave noble lord” in Taino. In the center, there is also the cacicazgo of Coanabo, whose name means “the great leader of the earth”, and whose cacique was the first ruler to oppose the Spanish invasion.

Throughout these different figures and maps, one can gain a more thorough understanding of the socio-cultural trajectory of the Caribbean, as well as how European colonization disrupted, and at often time decimated, traditional indigenous societies in the region.

My next steps are narrowing the focus of my research question, to decide exactly what aspect of the cartography I want to study, but I also want to gather data from recent years to compare to the data that is provided by the maps. I would like to use these materials to make a contemporary comparison project about the Caribbean Sea and its islands.

I hope you have enjoyed all this, and see you soon for another update blog post!