Enjoy this post by Kobi Khong, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2020-2021 academic year!

Whether you’re a lover of lox or a lover of lore, a biter or a writer, a baker or a note-taker, you’re in for a treat! Make sure you don’t spill, because today we’re going to be putting the bib in bibliophile as we dive into the sometimes sloppy, sometimes spicy, forever finger-lickingly flavorful history of Asian American Cuisine—Udon(‘t) want to miss this!

This past year I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to work on researching and building upon our Sheridan Libraries’ Special Collections treasure trove of cookbooks, which detail the meals and memories of human history. As I parsed through pages of parsley, I found a topic that connected with me. My parents were immigrants from Vietnam who fled during the war; in a blink of an eye they went from being children running barefoot through rice paddies to refugees in a country 10,000 miles away from their home. They couldn’t return home, but when they missed their lives, they would nh?u. With their family and friends they would all come together, sharing foods and sharing stories from dusk until dawn and with every mouthful of mì Quang and every slurp of Oc len xào dua they would be transported back to their childhoods.

To understand the introduction of Asian cuisine to the Americas, we have to understand that history and food are intrinsically entwined; the culture that we see today is as a result of pivotal moments of history. At first glance, food may seem like a relatively tame and uninteresting topic, but it’s a culmination of a millennia of human interactions, all of which must be considered in the context of food. I will be taking you through a chronological journey of how Asian food found a home in America, many based on books and pamphlets that I helped to select for Special Collections acquisition!

One of the first glimpses into the relationship between the West and the East in the world of food found in our Special Collections, comes from a somewhat unlikely source: “Desserts of the World,” a pamphlet of recipes meant to advertise The Genesee Pure Food Co. a now defunct business that was the start of a little bouncy product called Jell-O. Now although the culinary authenticity of Japanese families dressing in kimonos gathering around their “JELL-O” branded Cherry Almond desserts is somewhat dubious, this first insight into the western perception of Asian culture is exciting.

A few years later, we would have the Chinese-Japanese Cook Book! This is the first American cookbook to prominently feature Japanese recipes within its pages and one of the earliest to feature Chinese recipes. In the preface of the cookbook, Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna discuss the purpose of the book, how the Chinese and Japanese recipes dishes were specifically chosen with the Western audience in mind, including palettes and instructions that could introduce Asian food to the West. With the introduction of food there’s also the introduction of culture, this first step in appealing to Western audiences is a stepping stone to where we are today!

The Chinese Cook Book by Shiu Wong Chan is the eighth published Chinese cookbook in North America, and just the second one actually authored by a Chinese-American. It includes one hundred fifty-one recipes, each presented with a title in English and in Chinese characters. Chan notes in the preface that the book is for both households and restaurants, which shows the path of how Asian cuisine starts to make it to the mainstream! Chan also explains the cultural context of some of the dishes. By explaining the history of Chinese food and Chinese culture, Chan is telling stories both literally through these narratives but also through the food that is meant to be shared with family and friends.

In 1922 the guidebook, Good Cooking and Health in the Tropics was published by The American Guardian Association, an organization created to provide support, education, shelter, and medical care to Filipino children abandoned by their G.I. fathers. This cookbook raised money for those children, but also contained guides on living in the “tropics” such as dealing with weather,locating ingredients to make both western-style and Filipino cuisine, and life advice, including one recommendation that is relevant to this day — a call on the importance of vaccination: “why endanger life and happiness when harmless vaccination will give this enormous protection.”

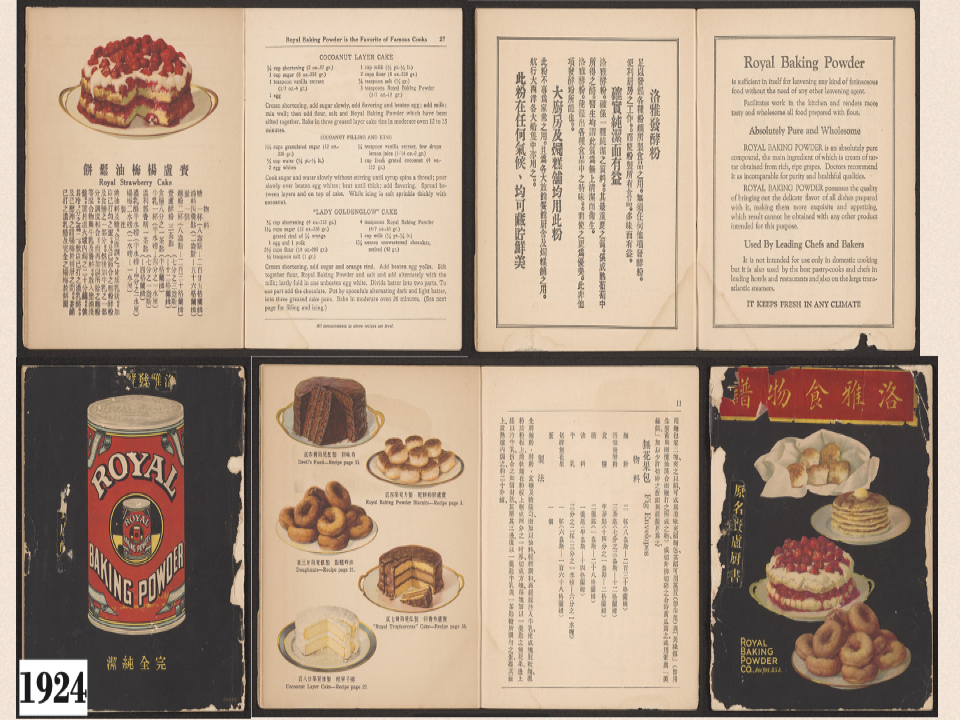

This next cookbook pamphlet Royal Baking Powder Company, is especially unique from the other novels of nourishment we’ve covered because rather than being APIDA dishes for an American audience this is the exact opposite! This cookbook slash advertisement from the Royal Baking Powder company is full of recipes for American desserts like strawberry cake and doughnuts, but they are translated into Chinese, for a Chinese audience; this marks the beginnings of the recognition of Asian Americans as consumers of American goods, with buying power that companies could appeal to.

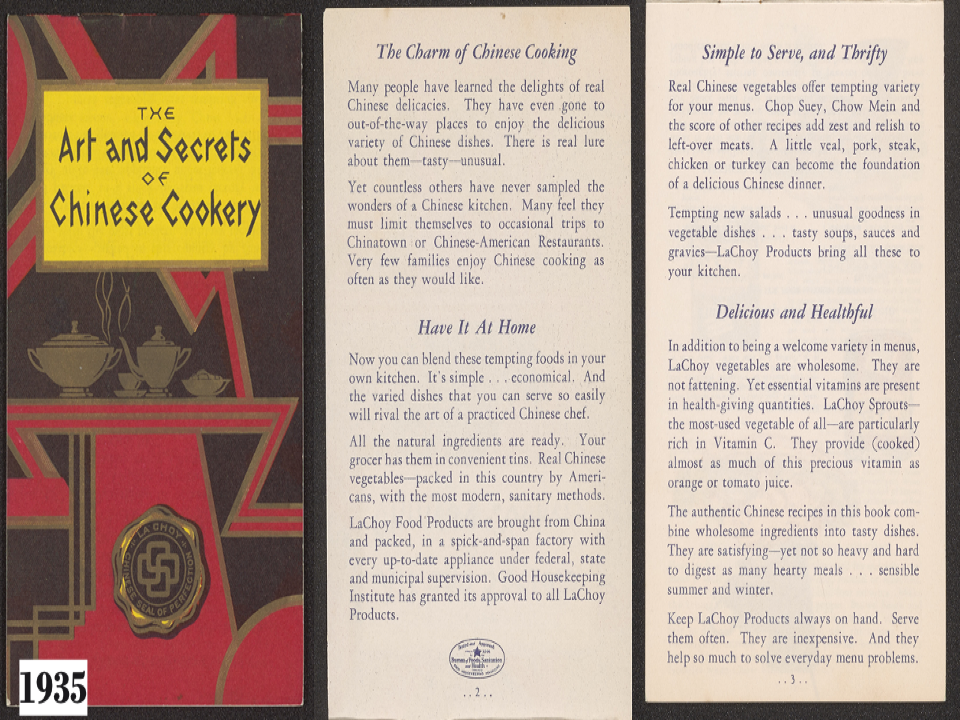

The Art and Secrets of Chinese Cookery, produced by La Choy Foods also has an interesting role in the history of Asian food in America. La Choy Foods was founded in 1922 by college friends Wally Smith and Ilhan New. They started selling canned bean sprouts, which proved to be a very successful endeavor. They expanded their business by bringing more canned produce and sauces to the American marketplace, contributing to the popularity of East Asian cuisine throughout the U.S. This commercialization of Asian cuisine in America, though pouring chow mein out of cans may sound rather unsavory to some, is a huge milestone in terms of cultural firsts.

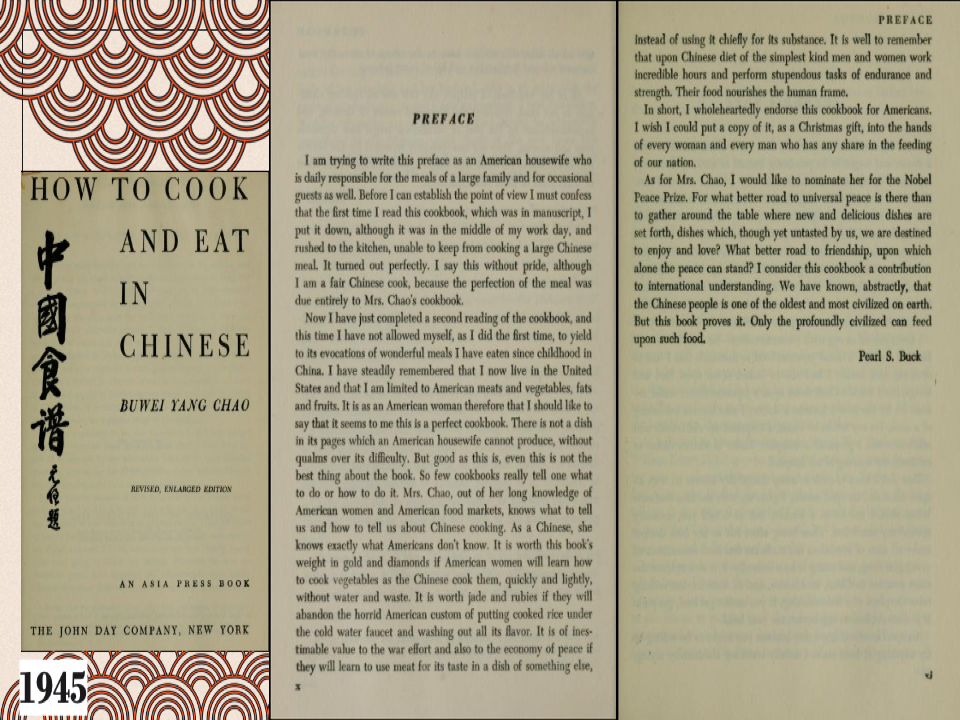

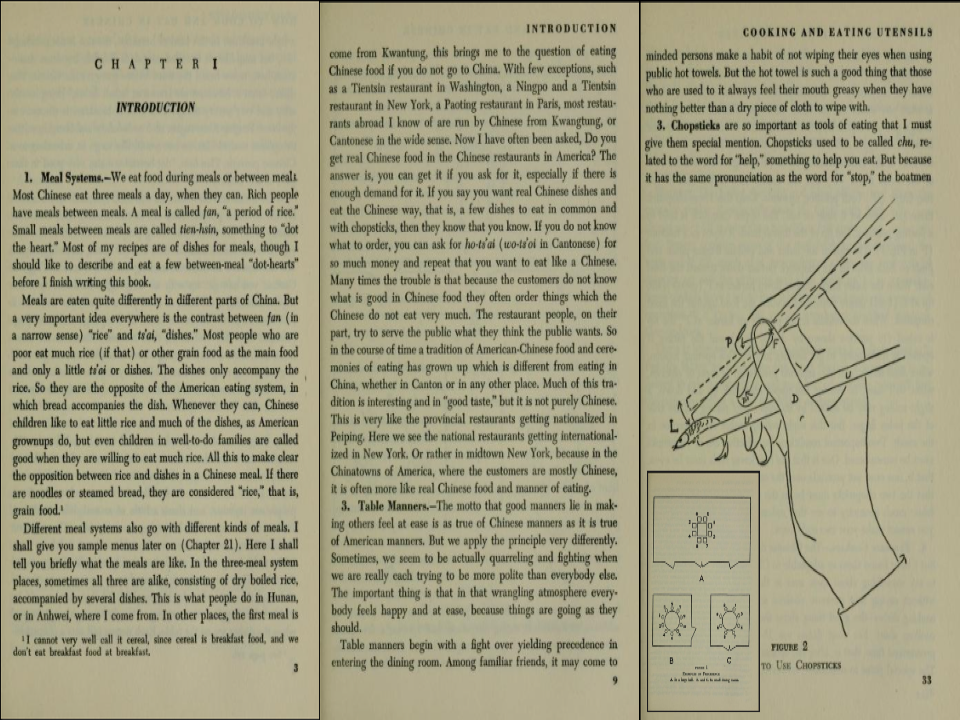

This next book is considered one of the most monumental in terms of impact on Asian American history: How to Cook and Eat in Chinese by Buwei Yang Chao. This preface written by Pearl Buck gives a little insight into why this book was able to be such an important factor in introducing Eastern cultures to the United States:

“As for Mrs. Chao, I would like to nominate her for the Nobel Peace Prize. For what better road to universal peace is there than to gather around the table where new and delicious dishes are set forth, dishes which, though yet untasted by us, we are destined to enjoy and love? What better road to friendship, upon which alone the peace can stand? I consider this cookbook a contribution to international understanding.”

The thing about Buwei Yang Chao that is somewhat ironic and somewhat exactly perfect, is that Buwei is not whatsoever a cook. She’s actually famous for a different reason, being one of the first women to practice Western medicine in China! She wrote a cookbook, with translation help from her daughter and her husband, because she wanted to share her food with the world. Her husband Chao Yuen Ren is also not a chef, and also famous for an entirely different reason. He’s a linguist who invented a new method of phonology called the “gwoyeu romatzyh romanization scheme of languages,” (which after I saw on his Wikipedia page and took a single glance at and both consciously and subconsciously decided to not even try to comprehend). His contributions were witty names and explanations of the recipes; the words “stir-fry” and “pot stickers” are from him, yet at the same time some of it was a hit or miss, “ramblings” for wontons, or “leaking ladle” for slotted spoon didn’t catch on. It seems odd that this book is the origin story for so many names, but Asian dishes and Asian cultures were still somewhat new to an American audience. Translations of names of foods are test runs and sometimes they (pot-)stick, but sometimes they’ll change or adapt.

This last book we’ll cover, Recipes Out of Bilibid like all of our other cookbooks has a lot of history. During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II, Bilibid was a prisoner of war and civilian internee camp where civilians and American soldiers were held. Recipes Out of Bilibid was a community cookbook collected by Col. H. C. Fowler, a prisoner at the camp. Each recipe contains a story about the soldier who contributed that recipe. Dorothy Wagner who compiled the recipes wrote a preface that has a really wonderful explanation about why food was so important to the people at the camp :

“It strengthened their resolution to survive, if only because it made more vivid, not what they sought to escape from, but what they were resolved to return to. It brought close to them the homes waiting faithfully for them, homes in which the primal need to nourish the body was recognized as a perpetually renewed adventure, a challenge to the imagination, an invitation to cheerful sociability.”

When people immigrate they don’t do it alone, along with them comes the culture and the food and the histories that contribute to our melting pot. Yet, it’s not a fairy tale ending. Within our country and our communities, Asians and Asian Americans have faced violence and discrimination which we saw escalated throughout this last year during the pandemic. Sharing meals is important, but it is not a prize for unity. It is a single step alongside educating ourselves and our communities, standing in solidarity with those discriminated against, and a plethora of other tasks that we have to work on to reach our goals.