Working with historic sheet music, I come across autographs almost every day. This doesn’t surprise me, as most of the books on my own bookshelf have my name written inside. Likewise, sheet music was intended to be used frequently, making the contents of any historic sheet music collection far from ‘mint condition.’ Instead, most of our songs exhibit all the signs of loving use—small tears, separated pages, pencil markings, slightly discolored sections where a performer might have frequently turned the page. And lots of autographs.

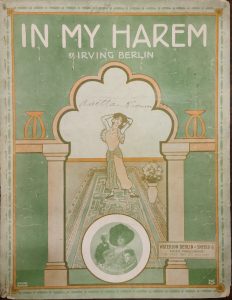

And every time I find one, I get to scrutinize it to determine if it’s just the signature of the song’s owner or if it’s signed by a celebrity. Most fall into the former category, like the song below (quick note here—I’ll be using the terms ‘signature’ and ‘autograph’ interchangeably, recognizing that a signature functions more as a legal entity).

This one isn’t too difficult to decipher as an owner’s autograph, as Annetta’s name appears in three different places on the cover in pencil—twice as Nettie, with one instance mostly erased. It’s also easy to tell that Annetta is not the composer of the song (Irving Berlin) or the performer pictured at the bottom (Sadie McDonald).

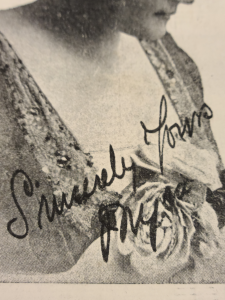

However, autographs often turn out to be from someone of note, and the resulting scrutiny can become much more difficult. Most sheet music covers in the mid-19th century onwards were printed using the process of lithography—basically, the artist would draw a design on limestone with an oily pencil. The stone would then be dampened so any oily ink applied afterward would stick to the pencil and not the wet stone, as oil and water don’t mix (the Museum of Modern Art has a terrific demonstration of the process here). Using this pencil, a celebrity could ‘sign’ the original stone and have their autograph automatically printed on every copy. Alternatively, photolithography could be used to photograph any image (such as an autograph) and duplicate it.

For example, the signature on the above song from 1912 appears to be handwritten. However, zooming in, the ink appears almost pixelated– clearly not done with fresh ink.

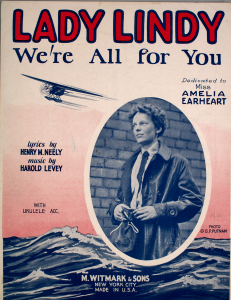

In combing through Lester Levy’s fifteen boxes of correspondence, I happened to find a short letter mentioning a song with Amelia Earhart’s signature on the cover. Sure enough, the cover (above) appeared to have the signature just to the left of Earhart inside the oval. The signature resembled a verified autograph found online, so my next step was to find a copy of the song in another repository. A copy in the Owls Head Transportation Museum does not have the signature, so we know the autograph was not part of a lithograph and is likely authentic.

Other signatures can be verified with historic context. For example, we know from his correspondence that Levy was acquainted with popular composers Ira Gershwin and Irving Berlin, so it’s not surprising to find their signatures throughout the collection.

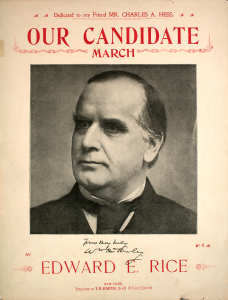

The above song, Our Candidate March, presented a significant challenge in verifying the supposed signature of President William McKinley. An initial search didn’t turn up any other editions of the song, so I took a fieldtrip down to our conservation lab to examine the signature under a few different microscopes. However, it was almost impossible to tell if the signature is unique or part of an original lithograph. There were a few clues it may be authentic—there is a slight smudge on the “l,” and the “y” does cover the “e” in the composer’s name. There is also the slightest bleed of ink through the page, but no impression from a writing implement. Eventually, I managed to track down another edition of the song at the New York Public Library. They confirmed that their edition does not have the signature, meaning ours is most likely legitimate.

Of course, proving the signature was made with unique ink doesn’t prove it was McKinley himself holding the pen. Nowadays, there are even autograph machines that can hold a pen and be programmed to reproduce a signature. Regardless, each venture down an autograph rabbit hole inevitably yields more insights than I thought I’d find (for example, I now know all of the variations of “i” dotting in McKinley signatures). And, the next time you scribble your name on the inside of a book cover, you can wonder if future researchers & historians will be examining it under a microscope to determine if it was truly your hand that put pen to paper.

As the curator of the Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection, a phrase I hear often is “I didn’t know sheet music could be used to study…”

Levy collected 30,000 songs over 50+ years not to perform, but to use as a lens for studying history. To make this easier, Levy organized his collection by subject, rather than title or composer. As a result, there are hundreds of unique subjects that can be used to filter the collection. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to dive into some of the more fascinating, obscure, and strange subject headings in the collection. Each week, I’ll focus on a different subject — stay tuned for more deep dives! You can view the entire digitized collection here.