Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of texts from the 1820s through the 1930s by North American women who brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our series title, please see the first post. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post, the last in our series, is by Anna Leoncio, Class of 2020, a major in Medicine, Science, and the Humanities.

The Dakota writer and activist Zitkála-Šá advocated for the preservation of Native American culture for most of her life. As a young girl, she was persuaded to leave the Yankton Sioux reservation to receive an education at a white boarding school. While there, white missionaries tried to force Zitkála-Šá to abandon her Dakota culture and adopt their white American culture. This traumatic experience drastically changed her, but it also planted the seeds for her later critique of Indian boarding schools and her activism on behalf of Native Americans rights.

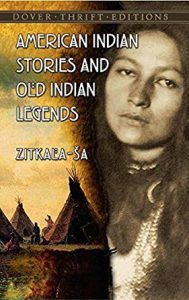

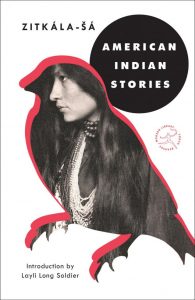

Zitkála-Šá’s writing has remained in print since she first began publishing in 1900. Her book American Indian Stories, in which she writes about her childhood experiences, has been republished several times since its original printing in 1921. Each of these editions has delivered different visual representations of the author and her work through cover art. Here, I will examine four different editions of American Indian Stories—the original and three twenty first-century editions—to see what each suggests about the tactics publishers used to attract readership to Zitkála-Šá’s works. This survey of covers also offers a glimpse of how American society’s perception of Indigenous people has changed from the days since Zitkála-Šá wrote her book.

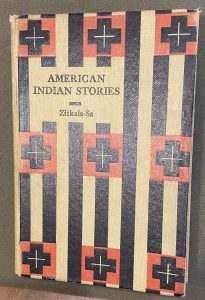

The first edition of American Indian Stories from 1921 was distributed by Hayworth Publishing House and would have been seen by Zitkála-Šá herself. In fact, the copy held at the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries includes an inscription by her to an unknown person that states, “We are friends.” The cover features a red and black geometric pattern adorning both the front and back. While I have not been able to confirm if the pattern is a traditional Dakota Sioux pattern, it appears to at least mimic the artistic style featured in Sioux art and clothing; see below. Additionally, the color scheme could perhaps be an homage to Zitkála-Šá’s name, meaning “Red Bird.”

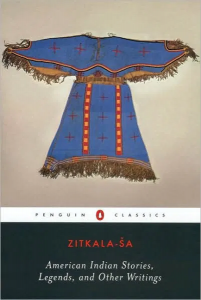

The publisher’s decision to include or gesture towards Sioux art continues in more modern publications as shown in the 2003 publication of her book by Penguin Random House. This edition features a depiction of “Girl’s Dress” on the cover. This particular dress was made by people of the Dakota/Eastern Sioux and was reportedly worn by Minnie Sky Arrow, a pianist and member of the Sioux people. The design seems to be typical of Sioux dresses, as is evident in comparison to one in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum. While it is culturally accurate, the dress is unrelated to Zitkála-Šá herself. Instead, it seeks to achieve a similar goal as the cover of the original publication. Should a reader see this cover, they can associate what is recognizable as Indigenous art with the contents of the book without much background knowledge.

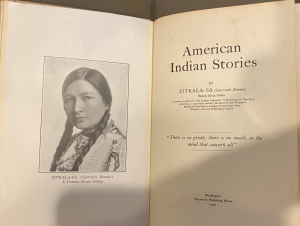

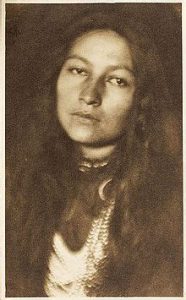

Both a Dover Thrift edition of 2014 and a Modern Library edition of 2019, discussed in more detail below, similarly follow strategies established by the original publication, as both of their covers feature portraits of Zitkála-Šá. In the original publication, a photographic portrait from around 1895 serves on the inside as the frontispiece. In lieu of an interior portrait, both newer editions include her image on the cover, but neither show the image from the original publication.

I could not find much information about this portrait, other than that it is held by the Library of Congress and is a photo-mechanical print, meaning that it was transferred to the book using an inked plate, not photographic processes. However, compared to the two portraits that follow, this one depicts her as more reserved, with a neutral expression on her face and her hair formally plaited.

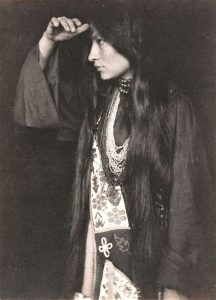

The 2014 Dover Thrift edition features a portrait of Zitkála-Šá that is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The original photograph was taken by Joseph T. Keiley, a lawyer and photographer who sought to connect artists in different realms of art like painters and photographers. Sometime between 1898 and 1901, Joseph T. Keiley met Zitkála-Šá in New York when she was performing with the Carlisle Indian Band as a violinist, during which time he took several photos of her including the two below.

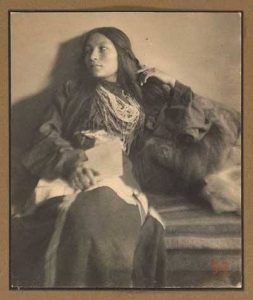

Lastly, the most recent 2019 edition published by the Modern Library features a portrait of Zitkála-Šá that is housed in the National Museum of American History. This photo was taken by Gertrude Kasebier in 1898 and is similar to Keiley’s portrait in spirit. Here, Zitkála-Ša’s takes up more of the frame and she looks off into the distance with her hand shading her eyes as though she is searching for something. She is more dynamic and has more agency than in the frontispiece portrait of the first edition. Additionally, she is dressed in a mixture of tribal and Western clothing, alluding to her mixture of experiences and the spaces in which she works.

In all of these different editions, the publishers have tried to create a visual indication to readers of the contents of Zitkála-Šá’s book. In the first edition, the cover and portrait simply indicated that the author was Indigenous, telling stories from her community, but this set of visual signals has gradually expanded. Later publishers also utilize depictions of what would be easily recognizable as Native American culture, with “Girl’s Dress” and Bierstadt’s painting. However, the change that I personally enjoyed was how, through the differing choices of portraiture, the covers of more recent editions have come to demonstrate more of Zitkála-Šá’s agency. The resistant spirit so evident in her writing becomes more visible on the cover, and readers just need to glance at the book to see it.

Works Consulted

“Albert Bierstadt.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://americanart.si.edu/artist/albert-bierstadt-410

Bierstadt, Albert. View of Chimney Rock, Ohalilah Sioux Village in the Foreground. 1860. Oil on board. Colby College Museum of Art. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from http://browse.americanartcollaborative.org/object/ccma/1743.html

Campbell, Donna M. “Zitkala-Sa: Bibliography of Secondary Sources.” (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/zitkalabib.htm

“The Dakota People.” Minnesota Historical Society. No date. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from http://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/native-americans/dakota-people

Fisher, D. “Zitkála-Šá: The Evolution of a Writer.” American Indian Quarterly, 5(3), 229–238. JSTOR. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.2307/1183520

Girl’s Dress, Dakota (Eastern Sioux), Yanktonai or Lakota (Teton Sioux), ca. 1900. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/639662

“Joseph T. Keiley.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. No date. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://americanart.si.edu/artist/joseph-t-keiley-6695

Juravich, N. “Life Story: Zitkála-Šá.” Women & the American Story. No date. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://wams.nyhistory.org/modernizing-america/xenophobia-and-racism/zitkala-sa/

Kasebier, Gertrude. Zitkála-Šá, Sioux Indian and activist. ca 1898. Platinum Print. National Museum of American History. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1006125

Keiley, Joseph T. Zitkala-Sa. 1898. Photogravure. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institutions, Washington D.C. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_S_NPG.79.26

Keiley, Joseph T. Zitkála-Šá. 1898. Photogravure. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. Google Arts and Culture. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/zitkala-sa-joseph-t-keiley/1wFjdaBhkk7sOA

Pair of Parfleches, Brulé Sioux. 1880-1885. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/319188

Possible Bag, Sioux. ca. 1900. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/827407

“Photomechanical Prints.” Preservation Self-Assessment Program. No date. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide/photomechanical

Zitkála-Šá. American Indian Stories. Washington: Hayword Publishing House, 1921. Digital. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from http://www.digital.library.upenn.edu/women/zitkala-sa/stories/stories.html

Zitkála-Šá. American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings. No date. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://www.penguin.com/ajax/books/excerpt/9780142437094

“Zitkala-Sa, American writer.” Encyclopedia Britannica. April 26, 1999. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zitkala-Sa

Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Bonnin), a Dakota Sioux Indian. 1985. Photomechanical Print. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://www.loc.gov/item/97513497/

“Zitkála-Šá (Red Bird/ Gertrude Simmons Bonnin).” U.S. National Park Service. No date. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://www.nps.gov/people/zitkala-sa.htm

“Zitkala-Sa.” Akta Lakota Museum & Cultural Center. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2020, from http://aktalakota.stjo.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=8882