Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of texts from the 1820s through the 1930s—speeches, private writings, and published poetry, fiction, and journalism—by North American women who brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our series title, please see the first post. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post is by Addy Perlman, Class of 2021, a Writing Seminars major.

Frontispiece portrait of Ida B. Wells from A Red Record, [1892/1894]. Image from Library of Congress.

Journalist Ida Bell Wells-Barnett used her pen to battle injustice. She was born on July 16, 1862 to James and Lizzie Wells, who were enslaved in Holly Springs, Mississippi. After the Civil War, her father helped found Shaw University (now Rust College). Wells went to Rust College for part of her education, but yellow fever left her orphaned, and she assumed the role of her siblings’ guardian. Having to care for her siblings as if they were her own children, she “convinced a nearby country school administrator that she was 18, and landed a job as a teacher” before she and her siblings moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where their aunt would care for them (“Ida B. Wells”). Evidently, even at a young age, Wells was able to see and understand problems and then address them.

As an African American woman, Wells experienced and fought back against the Black codes and “Jim Crow” throughout her life. In 1883, while riding the train from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee, where she taught school, she was forced to re-locate to the smoking car, where African American passengers were required to ride, even though she had purchased a first-class ticket. The following year, she sued the railroad. She saw a moment of success when she won her case, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the ruling made by the circuit court. After facing this level of racial injustice, Wells chose the pen name “Iola” and started to write; her writing led to her co-ownership, in 1889, of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, a newspaper in which she also continued to publish her work. Her attention turned to the horrendous lynchings in the South because of three men in Memphis: Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart. The three men had opened a grocery store, which competed with a white-owned store in the neighborhood. The white store-owner sought revenge and a violent clash ensued. The Black store-owners were arrested and hauled off to jail. A few days later, they were taken from jail and shot by a mob of masked men. It was this 1892 incident that prompted Wells, who was friends with Moss, to launch her most important work as an investigative journalist.

Wells initially published a series of anti-lynching editorials in her newspaper. Then, traveling throughout the South, Wells conducted interviews and dug up records on other lynchings. She learned that, often, “lynch victims had challenged white authority or had successfully competed with whites in business or politics” (Steptoe). She particularly wanted to unveil the “stereotype that was often used to justify lynchings—that black men were rapists. Instead, she found that in two-thirds of mob murders, rape was never an accusation. And she often found evidence of what had actually been a consensual interracial relationship” (Dickerson). She compiled her research into Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, which was published in 1892 as a pamphlet, and continued her analysis in A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, a pamphlet published a few years later.

Cover of Ida B. Wells, “A Red Record.” Chicago, [1894]. Image from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Wells’ anti-lynching journalism, characterized by empirical evidence, impassioned prose, and myth-busting discoveries, earned her the nick-name “The Princess of the Press” (Dickerson). As she wrote in her preface to Southern Horrors, “Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so”—and she did, despite great personal sacrifices. After publishing her anti-lynching pieces in her own newspaper, for example, Wells “was run out of the South—her newspaper ransacked, and her life threatened” (Dickerson). Nevertheless, she procured a sliver of justice for the victims of lynching by recording these abominable crimes.

First Editions

A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States. Chicago: Donohue & Henneberry Printers, [1892/1894].

A complete scan available at the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mfd.40021/

Selected page images available at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/red-record-tabulated-statistics-and-alleged-causes-of-lynchings-in-the-united#/?tab=about

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. New York, [1892].

A complete scan available at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/868f8db7-fa74-d451-e040-e00a180630a7.

Chronological List of Selected Later Editions

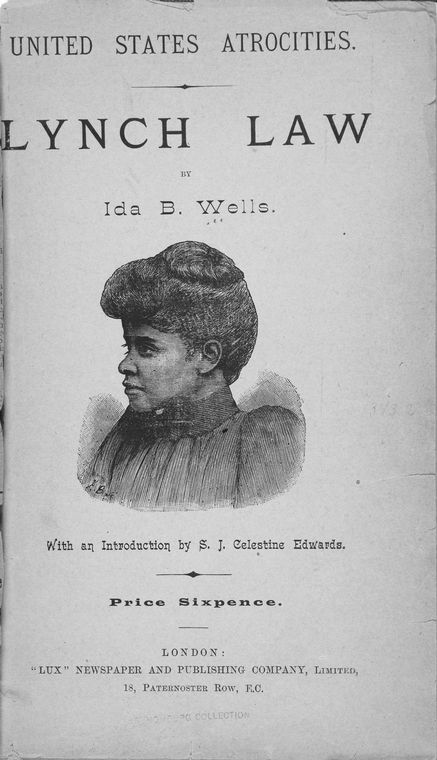

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. United States Atrocities: Lynch Law. London: “Lux” Newspaper and Pub. Co., 1892. British edition of Southern Horrors.

Cover of Ida B. Wells, United States Atrocities: Lynch Law, London, 1892. Image from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

—–. On Lynchings: Southern Horrors, A Red Record, Mob Rule in New Orleans. New York: Arno Press, 1969. Print.

—–. Selected Works of Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Edited by Trudier Harris. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Print.

—–. Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892-1900. Edited by Jacqueline Jones Royster. Boston: Bedford Books. 1997. Print.

—–. The Red Record. Project Gutenberg E-Book, 8 Feb. 2005. Digital.

—–. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases. Project Gutenberg E-Book, 8 Feb. 2005. Digital.

—–. The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynching Crusader. Edited by Mia Bay. New York: Penguin Books, 2014. Print.

—–. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States. Cavalier Classics, 2015. Print.

—–. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Adansonia Press, [2018]. Print and digital.

Selected Additional Writings

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Alfreda M. Duster. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970. Print.

—–. The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Miriam DeCosta-Willis. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

——. The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not In the World’s Columbian Exposition. Chicago, [1893].

E-book available at A Celebration of Woman Writers. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/wells/exposition/exposition.html#

—–. Selected newspaper articles from Chronicling America, Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-ida-wells/selected-articles

Archival Holdings

Ida B. Well Papers 1884-1976, University of Chicago, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.IBWELLS.

Additional Works Consulted

Dickerson, Caitlin. “Ida B. Wells.” Overlooked No More. The New York Times, 8 Mar. 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-ida-b-wells.html.

Guide to the Ida B. Wells Papers 1884-1976. University of Chicago Library. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.IBWELLS.

“Ida B. Wells.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 27 Feb. 2020. https://www.biography.com/activist/ida-b-wells.

“Ida B. Wells (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/people/idabwells.htm.

Steptoe, Tyina. “Ida Wells-Barnett (1862-1931).” The Black Past, 19 January 2007. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/barnett-ida-wells-1862-1931/