Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of texts from the 1820s through the 1930s—speeches, private writings, and published poetry, fiction, and journalism—by North American women who brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our series title, please see the first post. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post features pieces by Gia Squitieri, Class of 2020, a psychology major, and Erin Baggs, Class of 2020, an environmental science major, examining in different ways the legacy of the writer Lydia Maria Child.

[Portrait of Lydia Maria Child] by John A. Whipple, Boston, ca. 1865. From the Library of Congress.

Lydia Maria Child’s story, “The Indian Wife,” was published in 1828 in The Legendary, Consisting of Principle Pieces, Principally Illustrative of American History, Scenery, and Manners, edited by Nathaniel Parker Willis. A well-known abolitionist, Child frequently addressed matters of racism, slavery, and the marginalization of Black Americans in her stories and essays—most notably, in An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans and the Anti-Slavery Catechism. She also addressed the fate of Native Americans, Abenaki and Penobscots, in particular, as she learned more about these tribes upon a move to Maine at age 12. This experience alerted her to the difficulties many Native Americans faced at the hand of the United States government, such as colonization, disease, and poverty. Her most famous work in this arena is the novel Hobomok.

“The Indian Wife” is a short fiction about Tahmiroo, the daughter of a Sioux Chieftan, who falls in love with and marries a white Frenchman. For most of the story, her French husband is a nefarious, greedy, insolent man; “he assumed an affectionate manner towards his wife; for he knew well that one look or word of kindness would at any time win back all her love,” in order to convince her to sell her lands to increase his own wealth (203). After draining Tahmiroo’s family of all they possess, he ultimately abandons her and their young son. In her misery and desperation, Tahmiroo puts herself and her son in a boat, and rows them off the edge of a waterfall to their deaths.

One way to understand this story is to examine its publication context, which shaped its meaning for readers in the 1820s and continues to do so today. The Legendary was designed as a periodical anthology of significant artifacts. In the preface, editor Willis describes his aims: “it is intended as a vehicle for detached passages of history, romance, and vivid description of scenery and manners, materials for which exist so abundantly in our country” (iii). In assembling texts that displayed the beauty, culture, and history of North America and the new United States, The Legendary would promote uniquely American literature. Willis was not known to have any strong activist leanings, and his stance on the abolition of slavery was rather ambiguous (Foreman, 34).

Viewing “The Indian Wife” as part of this anthology, the potentially activist nature of her story—to generate sympathy for the unjust suffering of colonized people—could be called into question. If The Legendary was part of a political project to showcase American arts, the choice to include a story wherein a Native American family is ruined by settlers suggests conflicting motivations. On the one hand, the inclusion of a story in which the Sioux are represented as complex people with recognizable emotions and motivations and a distinct culture could be a progressive step towards humanizing an oppressed group. On the other hand, their depiction as helpless in the face of colonialism and the death of Tahmiroo could be seen as a form of white-savior charity, in which marginalized people are represented as helpless and in need of a white savior. In this case, the white saviors would be Child and Willis, the creators of this story.

Nowadays, “The Indian Wife” may be found in anthologies devoted to the works of Lydia Maria Child, such as A Lydia Maria Child Reader. Published in 1997, this collection of Child’s stories, essays, articles, extracts from longer works, and letters contains an introduction with information about her life and works, and highlights her life-long dedication to various causes. In this collection, her activism becomes obvious—the themes of women’s rights, justice for Native Americans, and the abolition of slavery appear repeatedly. In The Legendary, however, Child’s politics are not as visible. In a periodical designed to promote an emerging national culture, political critique was probably not desirable. To compare The Legendary (1828) to A Lydia Maria Child Reader (1997) is to examine the varying motivations behind the publication of an activist woman writer.

—Gia Squitieri

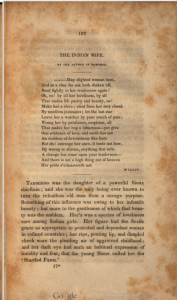

When our class first read “The Indian Wife” by Lydia Maria Child via the Google Books digital surrogate, it was still early in the semester and I had not yet fully grasped the implications of reading archival texts online versus in a physical form, let alone comparing different online formats of these writings. A couple of months later, searching for digital surrogates of our readings, I found a HathiTrust version of Nathaniel Parker Willis’ periodical anthology The Legendary, Consisting of Original Pieces, Principally Illustrative of American History, Scenery, and Manners, which contains “The Indian Wife” in the first volume. Here, I will describe my experience reading this incredible digital format and analyze what this version offered that I was not able to get from Google Books. I will also consider how the experience was different from reading the text in a physical form.

Child’s story is a dramatic and descriptive tale of a “gentle” and “submissive” Sioux princess, Tahmiroo, who falls for and marries a manipulative French fur trader, Florimond de Rancé. The relationship quickly turns sour, and Florimond drives Tahmiroo to row herself and her son over a waterfall (sorry for the spoiler). While Willis makes it a point to say that not all of the stories in the anthology follow his envisioned theme for The Legendary—“a vehicle for detached passages of history, romance, and vivid description of scenery and manners, materials for which exist so abundantly in our country” (iii)—I feel that Child’s story satisfies it in the best way possible. It provides Americans with a “historical” narrative of Native Americans—the one they want, at least—and supplements it with plenty of descriptions of scenery and customs. I digress; this post is not about the specifics of the story; it is about the experience of reading it on different platforms.

While the text provided by the two digital surrogates, Google Books and HathiTrust, is the same, it is truly amazing how much a high-quality scan of the original print book changes the way I feel when I read the story. The best way for me to describe the Google Books version is that it is washed out and bland, bleached of all life. There is no connection to the history behind this almost 200-year-old text. Scanning a text without color, first edition or not, strips it of so much of the emotion and power that a digital surrogate can hold.

Screenshot of “The Indian Wife” in The Legendary via Google Books / public domain.

When I found the HathiTrust format, a physical excitement came over me. How interesting! I now have access to the color and texture of the original book. The way that the tan pages are splotched with coffee-colored stains, called foxing, speak to the book’s age. The textured crinkles and indentations present across the frail paper makes me wonder who else has flipped through its pages? What dusty shelves has it rested on? Even more fascinating is that the pages are so thin that the text on the back of each scanned page can be seen, like a lurking shadow. I am more attuned to this story as it was told in 1828.

Screenshot of “The Indian Wife” in The Legendary via HathiTrust, from University of Minnesota Library / public domain.

As close as this scan comes to the printed book, there are components of the experience that are lacking. How heavy is the book? It has over 300 pages, so it must be a significant size and weight. What are its dimensions? How does it feel to turn each page? A digital format on HathiTrust and even on Google Books makes the stories widely available and allows readers in the present day, like myself, to experience the text in the font and style it was originally published in. If this class, Scribbling Women, has taught me anything, it is that there is no true replacement for the original, printed form of a text. Archival works can provide an understanding of the quality of the printing, the historical era it was printed in, and the care it was afforded by its owner long after the publishing date.

It is a bit hard to analyze printed forms of texts in the world right now, but excellent digital surrogates like the one of “The Indian Wife” on HathiTrust are helpful for the time being.

—Erin Baggs

Works Consulted

Child, Lydia Maria. “The Indian Wife.” In Nathaniel Parker Willis, editor, The Legendary, Consisting of Original Pieces, Principally Illustrative of American History, Scenery, and Manners. Volume 1. Boston: S.G. Goodrich, 1828. 197-207.

Foreman, P. Gabrielle. Activist Sentiments: Reading Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“Lydia Maria Child.” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lydia-Maria-Child.

“Lydia Maria Child.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/lydia-maria-child.