Enjoy this post by Natalie Thornton, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2019-2020 academic year!

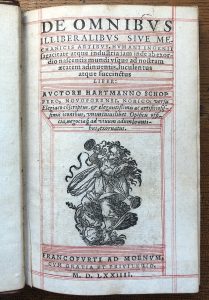

For my second installment of translations of later Latin texts as part of my Freshman Fellows research project, I bring you some excerpts from a late-16th Century book of trades. Originally published in Nuremberg in 1568 in German as Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stände auff Erden (True Description of all the Trades on Earth), it consisted of 114 woodcuts of different trades with an accompanying 8 line poem in rhyming couplets by the famous Meistersinger Hans Sachs. Sachs was himself a skilled artisan, a shoemaker, which makes his couplets all the more informed and interesting. An important Latin edition, Liber … de omnibus Illiberalis sive Mechanicis Artibus (A Book … on all the Illiberal or Mechanical Arts), by the humanist scholar Hartmann Schopper, and now grown to 132 images and 10 lines of Latin for each trade, appeared in 1574 at Frankfurt.

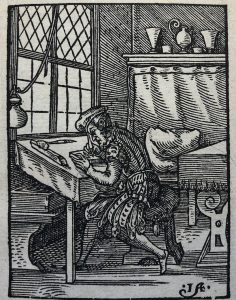

This 1574 edition is the one I worked with and which lives in Hopkins’ George Peabody Library. We will look at the full Latin title below, but perhaps most famous are the many woodblock images by the artist Jost Amman (1539-1591). Amman would have drawn these figures in ink before handing them off to a Formschneider, ‘Woodblock artist,’ who then carefully carved them in relief (think of a raised rubber stamp, though in this case, wood) for printing. Amman appears to have cut some of the blocks himself, as revealed by the small initials JA, Jost Amman, in the lower right of this image of the Sculptor (Woodblock-cutter) at work.

This image in the original measures a mere 6 mm wide by 8 mm high, giving a sense of the skill and steady hand required to carve each of these images in relief, and best by the natural light of a window. These ideas of light and shade are also reflected in the Latin of the full title as well, my translation follows:

De Omnibus Illiberalibus sive Mechanicis Artibus,

humani ingenii sagacitate atque industria,

iam inde ab exordio nascentis mundi usque ad nostrum aetatem

adinventis, luculentus atque succinctus Liber.

Auctore Hartmanno Schopero, Novoforensi, Norico, versu elegiaco, conscriptus: et elegentissimis ac artificiosissimis iconibus,

unius cuiuslibet opficis officia negotiaque ad vivum adumbrantibus, exornatus.

A brilliant and concise Book

on All the Illiberal or Mechanical Arts of human genius

which have already been discovered by means of acuteness and diligence

from the beginning of the newly made world up until our own age.

Written by Author Hartmann Schopper, of Neumarkt in der Oberfalz, in elegiac verse: adorned with the most elegant and most skillful images

depicting in true-to-life fashion the trades and businesses of

each and every single artisan.

Even in just the title of this work, there are some artful parallel clauses and alliteration with the sound of ‘ad’ in both parts: ‘ad nostrum aetatem adinventis’ (‘discovered up until our own age’) and ‘ad vivum adumbrantibus’ (‘depicting in true-to-life fashion’). There is also an interesting idea in this title of light and bringing the trades to light through the words ‘luculentus’ from lux (light), which we translated as ‘brillant,’ used to describe Schopper’s book and the idea of the shading in, or relief, the umbra in adumbrantibus, that we can see in the mechanical drawing, carving, and inking of the woodblocks used to print this very book. Notice the effect of light from the window cast over the Sculptor’s right shoulder and onto the cloth pinned up under the shelf above.

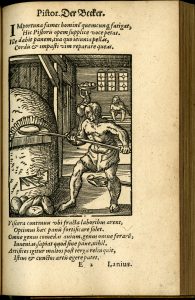

The first of the trades I translated was the ‘Pistor’ or ‘Baker’:

Pistor

Importuna fames hominem quemcumque fatigat,

Hic Pistoris opem supplice voce petat.

Ille dabit panem, tua quo ieiunia pellas,

Cordis et impasti vim reparare queas.

Viscera continuis ubi fracta laboribus arent,

Optimus haec panis fortificare solet.

Omne genus comedas avium, genus omne ferarum,

Invenias, sapiat quod sine pane nihil.

Artifices igitur multos post terga relinquit,

Istius et cunctos artis egere patet.

Burdensome Hunger wearies each and every man,

and so let this man seek the aid of the baker with a humble voice.

He will offer bread, by means of which you might drive away

your hunger pains, and you are capable of reviving the strength

of an unfed heart.

Where the hearts of men labor, broken with continuous effort,

The best bread is used to strengthen these hearts.

You might consume all kinds of birds, all sorts of beasts,

but you would discover that nothing has flavor,

which is without bread.

Therefore, although one can pass over many another craftsmen,

one is liable to need every craftsman of this singular art.

In reflecting on this passage, I remember a very distinct moment four years ago when my great uncle, now 91 years old, held up one of the dinner rolls from his store and said to his first great-grandchild at his baptism reception: “As long as you have this, you’ll be okay.” This seemingly trivial, and somewhat amusing, episode reinforces the main message between Schopper’s lines: the importance of good food and nourishment amid life’s labors. Just as the product of the baker’s art sustains all of the others trades by providing sustenance to the body as well as flavor to a dish, my great uncle’s own message was that we can always depend on bread because with its sustenance, anything is possible.

Just a few days after I returned to Cleveland in mid-March, while at dinner with family, my other great uncle, who is one of the people I look up to the most as he practices medicine and still exercises his passion for Latin, left the table to find a journal he kept in 1985, early in his career as a physician. He wanted to show me a few family trees he had recorded there. As he flipped through, he found a page where he had doodled a spider spinning its web along with the Latin quote “humilis artifex / mirabile opus” – “humble the craftsman, marvelous his work.” This quote really stuck with me due to its serendipitous timing, as it naturally reminded me so much of what I have been translating here—the word artifex ‘craftsman’ even appears in this excerpt describing the Pistor – a humble trade, but with marvelous and essential results! Here is a nice video showing craftsmen and women of Florence still producing marvelous work.

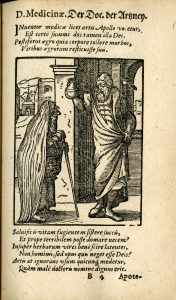

While home, I have been very fortunate to spend a few days seeing patients with this same uncle at his medical office. After almost forty years of serving his community as a physician, he just retired at the end of June. If things would have developed differently this past semester, I could have missed the opportunity to learn all that I have from his kind mentorship. It has been an honor to spend his last few days in the office with him as I gained my first exposure to the profession. With all of this in mind, I wanted to translate Schopper’s Latin description of a Doctor Medicinae:

Doctor Medicinae

Inventor medicae licet artis Apollo vocetur,

est certe summi dos tamen illa Dei.

Pestiferos aegro quia corpore tollere morbos,

viribus aegrorum restituisse suis.

Salvificis vitam fugientem sistere succis,

et prope terribilem posse domare necem.

Insuper herbarum vires bene scire latentes

non hominis, sed opus quis neget esse Deis?

Artis at ignorans usum quicumque medetur,

quam male doctoris nomine dignus erit.

It is right that Apollo is called the discoverer of the healing art

And more so as that gift is certainly from a most powerful god.

On account of the fact that this [gift of the] medical art is able

to remove destructive disease from a sick body,

and to restore the due strength of patients;

to halt fleeting life by means of healing liquids;

and to conquer a frightful death close at hand.

Moreover, who would deny that to know the hidden strength of herbs well,

that such work belongs not to men, but to the gods?

But whoever heals while ignorant of the best methods of this art,

how unworthy he will be of the name doctor.

My uncle has expressed to me that his profession is more of a calling than a job, and from what I have seen firsthand, not all aspects of the practice of medicine can be taught. Of course, there is the scholarly aspect to medicine that should not be overlooked: knowing the science, understanding research, looking at the evidence, being able to critically look at literature and use what you glean to better take care of patients. At the heart of medical care, however, is the human aspect: recognizing the patient’s particular social situation, ethnic and cultural background, and set of specific life experiences. These important factors allow you to treat a patient with empathy and humility. In this sense, the practice of medicine requires both knowledge and skill – it truly is both a science and an art. That is to say, there is a lot more packed into that word usus than may first meet the eye, as the practice of medicine requires much more than academic success. Today, this is what “the best methods of this art” truly entails.

Throughout this passage, Schopper is really celebrating both the supernatural powers of medicine (Apollo, as inventor medicae artis) and medical discoveries, while also issuing something of an admonition that those who would practice it must be as knowledgeable, as skilled, and as responsible as they can be. This would have had more of a satiric or critical ring to it in 1574, when doctors were often less knowledgeable and less highly trained, but it still rings true today. This sentiment reflects my own goals as I continue my studies at Hopkins: to learn as much as possible of the scientific principles of medicine (bene scire, line 7) from both books and time in the classroom, including my study of classical languages (Greek and Latin provide the foundations of medical terminology). By extension, the rewards of seeing medicine’s practical application (artis … usum, line 8) and human interactions with my uncle have had such an enriching experience in what I believe is the best approach to learning: learning by doing.

For my previous post on translating Latin, please see here.