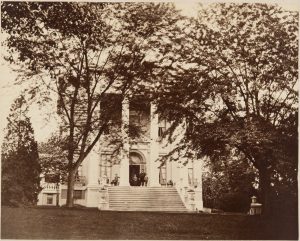

Greetings from Evergreen Museum & Library’s virtual office in my basement. For those of you new to us, the museum is housed in a 162-year-old Italianate mansion in the northern-most part of Baltimore City, about 2 miles from JHU’s Homewood campus. Evergreen was home to two generations of Baltimore’s Garrett family and is celebrated for its holdings of Asian arts; European paintings; art glass; and the John Work Garrett Library of rare books and manuscripts.

Since closing the museum to guests in mid-March, I’ve been thinking of ways to share information and stories about the museum virtually. I’ve also been researching aspects of the house’s history that have not been looked at closely before, particularly stories about the workers who built and maintained the 48-room house and its extensive grounds.

Some of the stories that I have come across shed light on labor trends and dynamics in nineteenth-century Baltimore, while others are quite a bit less scholarly, but still intriguing. The amazing online resources of the Sheridan libraries make it easy, and irresistible, to click and learn and then click and learn some more. Before you know it, you are deep into the life of someone or something only tangentially related to Evergreen but still oddly compelling, which is exactly how I came to learn about a giant turnip.

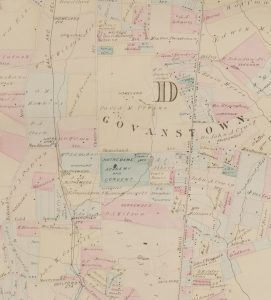

A few weeks ago, I spent some time pursuing research on the area surrounding Evergreen during the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. My goal was to glean a better understanding of the community of estates that developed in the area between Charles Street and York Road, bordered by Cold Spring Lane and today’s Stevenson Lane, prior to the Garretts’ purchase of Evergreen in 1878.

To answer these questions, I turned to census records and several maps from from the Sheridan libraries digital map collection, which show the names of the large landowners in the vicinity of Evergreen during the nineteenth century.

I learned that the Homeland neighborhood, to the north and east of Evergreen, was originally the 391-acre estate of David M. Perine (1796-1882). Evidence suggests that Perine’s home was, like Evergreen, Italianate in design. The Roland Park Company purchased the Perine estate for the development of a suburban community in 1924, following the 1922 death of David’s son Elias Glen Perine.

At the same time, I learned that the Kernewood neighborhood, to the south of Evergreen and boarding the Loyola campus, was a 1800s estate of the same name owned by James G. Wilson.

There is abundant information about the Perine family at the Maryland Historical Society and in the Baltimore Sun archives but the same is not true for Wilson. In trying to learn more about him, all I came across was this:

In November 1894 Wilson sent a 10.5-pound White Globe turnip to the offices of the Baltimore Sun. According to the Sun, the turnip “was raised by him at his county home, Kernewood, located at York Road and Cold Spring Lane.”

So, there you have it. Baltimore was once home to a giant turnip.