We take for granted that library books should not be written in, altered, and tracked with barcodes (if we let them out of the library at all). But before the invention of modern security measures, or even of circulating libraries themselves, book owners went to great lengths to protect their libraries from coming to harm. Medieval and early modern books were chained to benches, locked in chests, and even inscribed with curses to deter potential thieves from making off with them. Yet despite appearances, these books were intended to be shared and read by many, and to change hands carefully, if not frequently.

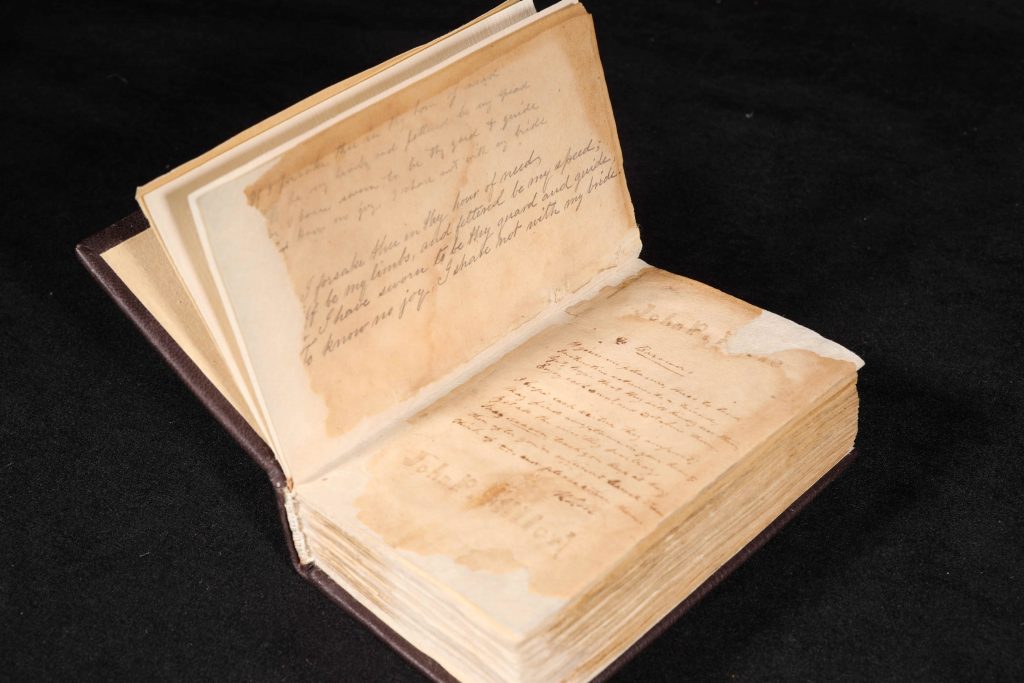

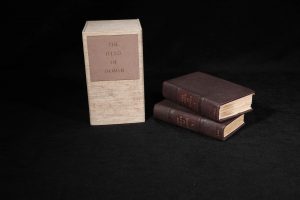

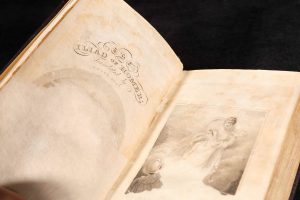

Aside from theft, we also go to great lengths to prevent books from deteriorating due to use. One of the best steps we can take after repairing a book is to put it in a box, protecting its covers from scratching or wearing, and preventing the heavy text blocks of large books from pulling out of their bindings. Opening one of these boxes is always a bit of a surprise, and this small box marked “The Iliad of Homer” was a pleasant one. This small format, two volume English translation of Homer’s Iliad (by Alexander Pope) is a local book. It was produced by the Philadelphia printers William Fry and Joseph Kammerer, but published in Baltimore and New York in 1812. What drew my attention, though, was the glimpse of a longer “library history” preserved in this verse on its front flyleaves.

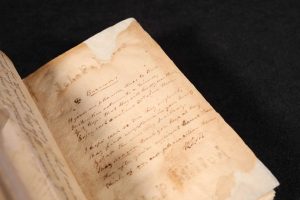

To Borrowers:

It gives me pleasure, these to lend

Instructive volumes, to a friend

Yet hope that they will kindly use them

Enjoy each sweet, and not abuse them.

I hope each virtue they impart, may find acceptance in your heart;

Yet all the vices they portray

May reason, teach you keep at bay

Then after you’ve sufficient learned them,

Think of me, and please return them.

W.P.M.

At this time, the only libraries in Baltimore were private collections (the first public, but non-circulating library, the George Peabody Library, was still seven years from its foundation). But as in centuries before, books circulated among groups of friends, especially when copies could be scarce. Sharing a small, locally printed book like this (as opposed to the first edition of the Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad, a seven-year effort which first appeared in six parts to subscribers only) carried less risk to Miller had a borrower not taken his advice, but still would have been an act of generosity, as he says, a risk worth taking for his friends.

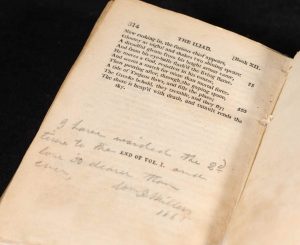

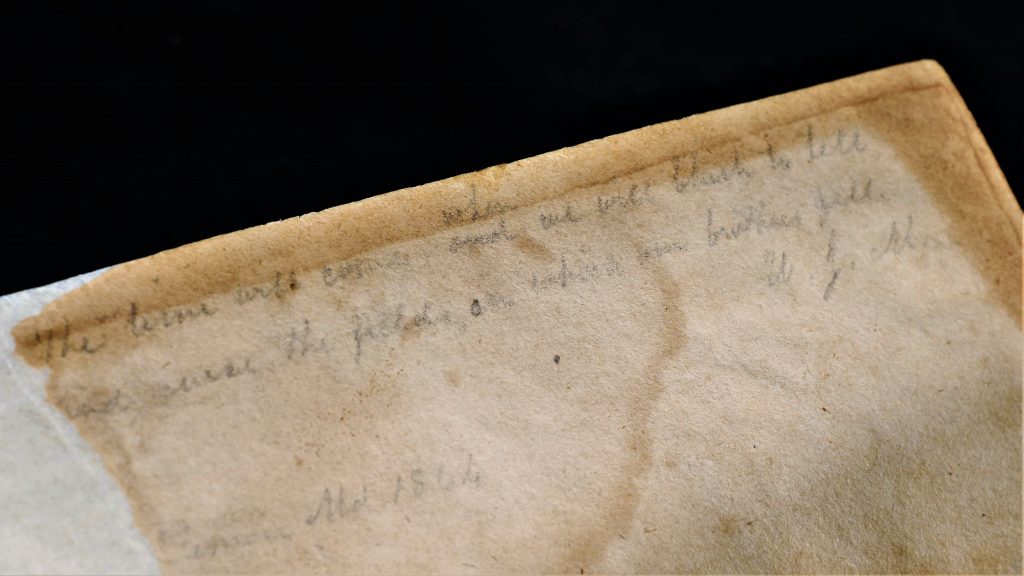

However, on the rear flyleaf, another penciled couplet signed and dated by Miller suggests that his second reading might have been brought on by less joyful circumstances.

The transition from private to institutional library came through a Hopkins librarian and alumnus, J. Louis Kuethe, who donated the book to Hopkins in 1936. Although the original bindings on the volumes were replaced, one set, preserved along with the copy in the box, bears a bookplate recording the gift. Opposite Miller’s poem to borrowers on the front flyleaf, a later hand which is possibly Kuethe’s has copied out a transcription of another poem which appears to be from Miller to his (also unnamed) wife. Keuthe, who spent over forty years at Hopkins as an undergraduate and then as assistant Librarian, assured that the Library would provide Miller’s book with ever more borrowers.

Studying the history of annotation in books allows us to catch small, often fragmentary glimpses of their uses across time and place. It’s rare, but not unheard of, to encounter readers like Miller, who provide so much information about when and why they read. When they do, however, they remind us that there is often much more to encountering, and sharing, a book than simply accessing its text. All carry pieces of stories, moments from books, in our minds, and every so often we leave pieces of ourselves in them as well.

We’ve come a long way from chaining them to benches or locking them in chests, and we’re lucky to have an excellent and talented group of conservators working in the library if a book ever gets in seriously bad shape. Before being boxed and rebound, the pages of these little volumes sustained heavy damage (possibly due to water) and have been meticulously repaired and strengthened, so that both its text, and its handwritten additions, can still be read.

You can’t come into Special Collections and ask for a book in a box, but if you ever do encounter one in our reading room, know that that book has had some extra (and recent) chapters added to its story to keep it in its current state. And no, sorry, you can’t follow the advice of this previous owner and take it home with you.