For most readers of classroom anthologies, Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) equals a jar on a hill, a 13-point blackbird or a snow-man. And those are all delicious poems in the signature Stevens key—poems that vibrate at the juncture of the familiar and the wild, poems that swerve between complexity and simplicity. We might expect that their composer reached this pitch of artistic dexterity after many years of treacherous experimentation. We might expect to find, behind the feats on display in our modern anthologies, lots of bad juvenilia. But in this case, we’d be wrong—or almost.

For most readers of classroom anthologies, Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) equals a jar on a hill, a 13-point blackbird or a snow-man. And those are all delicious poems in the signature Stevens key—poems that vibrate at the juncture of the familiar and the wild, poems that swerve between complexity and simplicity. We might expect that their composer reached this pitch of artistic dexterity after many years of treacherous experimentation. We might expect to find, behind the feats on display in our modern anthologies, lots of bad juvenilia. But in this case, we’d be wrong—or almost.

Stevens had an unusual career for a poet. Trained as a lawyer, he spent most of his working life in the offices of insurance companies; he published few poems until he was in his 30s, and was most productive in his 50s and 60s. (His first book, Harmonium, came out in 1923; his second, Ideas of Order, came out in 1935, and as a trade edition in 1936). Like other modernist poets, Stevens did not at first receive a warm popular reception. But he gradually accrued a host of honors; in the year of his death, he won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for his Collected Poems.

One way to understand the curious arc of Stevens’ career is to look at the trail of books he left in his wake. This is exactly what several undergraduates did a couple of years ago, exploring and elucidating Hopkins’ archive of printed material by and about Stevens.

Gabrielle Barr looked at the representation of Stevens in an anthology of magazine verse from 1921—yikes! He was outranked by a bunch of poets you’ve probably never heard of, at least according to the hand-written annotations in this copy. Books like this make it very clear that literary careers are made, not born.

Stevens was appreciated by other artists even before he received much popular acclaim—a state of affairs that is reflected in limited edition, fine-press books like the illustrated Cummington Press version of Esthétique du Mal. Ting Chang noted how this publication exemplifies its publisher’s ideas about Stevens’ fans: it is very definitely aimed at “a certain kind of literary readership.”

Stevens was appreciated by other artists even before he received much popular acclaim—a state of affairs that is reflected in limited edition, fine-press books like the illustrated Cummington Press version of Esthétique du Mal. Ting Chang noted how this publication exemplifies its publisher’s ideas about Stevens’ fans: it is very definitely aimed at “a certain kind of literary readership.”

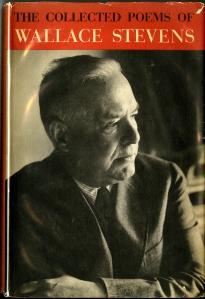

What about that popular acclaim, as embodied by the Collected Poems? Taylor Colvin observed that Stevens’ elevation to poetic sainthood is signaled by the portrait on the book’s dust jacket—a black and white photograph that “projects an air of nostalgia.” It’s a visual expression of his literary apotheosis.

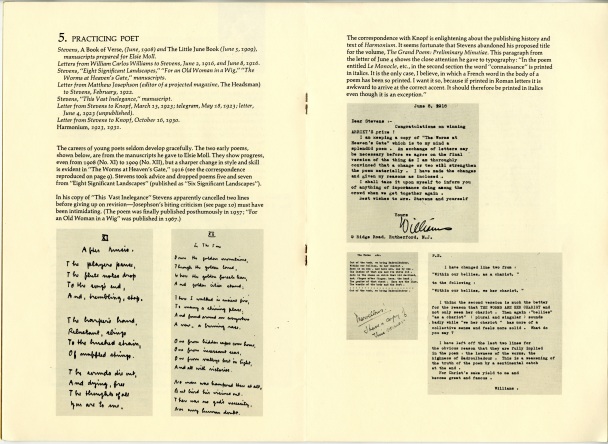

And his posthumous reputation? Well, it probably doesn’t get any better than an exhibition at the Huntington Library, as Mary Katherine Atkins discovered while examining the catalog for the exhibition. Artifacts that serve as emblems of Stevens’ career—his manuscripts in particular—are carefully reproduced in the catalog.

By the way: Stevens’ juvenilia (judge for yourself its merits) does exist in The Harvard Advocate and other collections of college verse. You can see our other Stevens material here!