The guest blogger for this post, Neil Weijer, is a Denis Curatorial Fellow at the Sheridan Libraries and a doctoral candidate in the Department of History. Weijer co-curated the Fakes, Lies, & Forgeries exhibition, which opens October 5 at the George Peabody Library and runs through February 1, 2015.

The guest blogger for this post, Neil Weijer, is a Denis Curatorial Fellow at the Sheridan Libraries and a doctoral candidate in the Department of History. Weijer co-curated the Fakes, Lies, & Forgeries exhibition, which opens October 5 at the George Peabody Library and runs through February 1, 2015.

As a species, we’ve had quite a lot of practice with deception. For proof of this, look no further than the Fakes, Lies, & Forgeries exhibition, which contains just some of the highlights of the Arthur and Janet Freeman Bibliotheca Fictiva Collection, itself a gathering of more than 1700 spurious works. (A tangled web indeed!) With little exaggeration, it is perhaps the greatest record of mankind’s long history of exaggeration, falsification, and outright forgery that has ever been assembled.

But like the Bibliotheca Fictiva, the exhibition is more than just a trophy gallery of hoaxes found out and pilloried in the public square. Perhaps the most interesting and amazing things about these items are the lives they took on after their initial creation, or “discovery.” Some gained staunch defenders along with fierce critics. Others re-shaped the course of history (or the naming of this country). Still more remain mysterious to this day—their authors, and even their aims, unknown.

Deciding what to put on display was difficult, since these fictions and forgeries come in all shapes and sizes. There is almost no limit to the range of people, places, and things caught up in their stories. Some items that made the cut were a late copy of what may have been the first “chain letter,” originally sent (it claims) by Jesus from heaven and still going strong over a millennium later; charters and law codes bearing the names of medieval kings; falsely attributed poems and plays; faked inscriptions and signatures; and even the concocted account of a local Baltimorean, Joseph Howard Lee, who in the early twentieth century toured America as LoBagola, a “savage” prince-in-exile from deepest Africa.

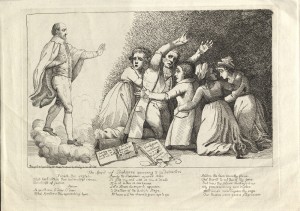

In the end, we chose to highlight the tangled web between truth and falsehood that is the true domain of forgery. For any deception to work, its audience needs not only to find it plausible but also to want to believe it. These items all play off of each other and off of us, their observers, exploiting gaps in our knowledge, as well as errors in our “common knowledge.” Sir Walter Scott would doubtless be irritated that his couplet makes an apt title for this blog post, not just for its content but because it is commonly attributed to Shakespeare (shown above—in ghostly guise—defending his good name from an eighteenth-century impostor, William Henry Ireland).

We hope you enjoy our guided tour through the dark corridors of deception. We promise you’ll have fun. Trust us.