If you’re a professional writer, you probably think a lot about how to get your work under the eyes of readers. You may weigh the advantages and disadvantages of self-publishing—using a service like CreateSpace on Amazon—against traditional publishing. (With self-publishing, there are fewer restrictions on your freedom of expression, but you miss out on the audience that publishers create by distributing and marketing your work.) You may wonder how changes in platforms—from print to digital, for example—will affect your ability to get your work out there. (Some readers prefer print, and e-books function differently on a variety of digital devices.) You may be surprised by new literary trends that make your work more popular—or less so. (Who woulda thunk so many grown-ups would read the Twilight books?) If you’re a professional writer, you’ve got at least two jobs: one is writing, and the other is keeping up with the business of writing.

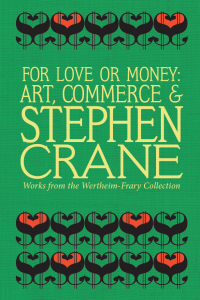

It all sounds very modern, very twenty-first century, right? But make a few changes to the paragraph above—remove the references to digital formats and adolescent vampires—and you’ve got a perfectly accurate description of the writing life circa 1895: the world of professional writing that Stephen Crane inhabited. You can get a close-up look at this world in For Love or Money: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane, an exhibition of rare books, letters, historical magazines, and other cool old documents exploring Stephen Crane’s work and the dilemmas of the writing life, from JHU’s very own Wertheim-Frary Collection of Stephen Crane. The exhibition is on view at the George Peabody Library in Mt. Vernon from March 4 through June 14. And it’s free!

It all sounds very modern, very twenty-first century, right? But make a few changes to the paragraph above—remove the references to digital formats and adolescent vampires—and you’ve got a perfectly accurate description of the writing life circa 1895: the world of professional writing that Stephen Crane inhabited. You can get a close-up look at this world in For Love or Money: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane, an exhibition of rare books, letters, historical magazines, and other cool old documents exploring Stephen Crane’s work and the dilemmas of the writing life, from JHU’s very own Wertheim-Frary Collection of Stephen Crane. The exhibition is on view at the George Peabody Library in Mt. Vernon from March 4 through June 14. And it’s free!

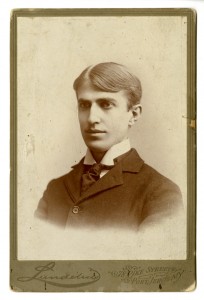

Stephen who, you say? Stephen Crane: you may have read his novel The Red Badge of Courage, or maybe Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. Both are classic works of fiction from a time when the literary marketplace was undergoing enormous shifts. The newspaper industry was expanding, new magazines were popping up left and right, and book publishers were trying out colorful graphic bindings and illustrations in the effort to attract readers. All of these changes had to do with technological advances in printing—like roller presses and wood-pulp paper-making—and major social transformations around the world. In the United States, immigration, urbanization, and public education generated a new population of readers. Industrialization produced a new class of goods that could be sold nationally and internationally, which gave momentum to an important revenue stream for publishers: ads. And the development of transportation networks across the country provided new ways to move commercial products—including reading material—from manufacturers to consumers. It was the apex of a great information age: the one just before our own.

The really interesting thing about Stephen Crane’s writing life is not just how his work documents all this cultural change—in his stories and books and articles about the urban poor, Western pioneers, soldiers, and small-town Americans—but also, how it exemplifies these changes, through the forms in which it was published. Sending a given piece to just the right magazine or newspaper, double-dipping in the English and American press, republishing stories in book form, Crane had to manipulate all the venues available to him—as well as his own reputation—in order to get by.

Watch this space for more about Stephen Crane’s career, and be sure to stop by the George Peabody Library for a first-hand glimpse of the writing life—circa 1895.