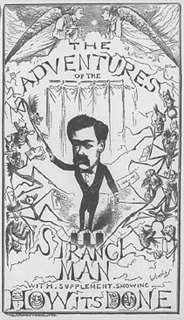

“I was born—that fact is undisputed and undisputable. I make no apology for that! but I apologise for appearing before you in the character of an autobiographist. I never wrote a book in my life. I have not written this, therefore I apologise twice.” So begins The Adventures of The Strange Man, Dr. H. S. Lynn, with a Supplement Showing “How It’s Done” (London, 1873), a rather Strange Book about magic tricks… but also, about theatrical life in the Victorian period, the performance of self in autobiography, world travel in the nineteenth century and, let’s face it, the art of total fabrication.

“I was born—that fact is undisputed and undisputable. I make no apology for that! but I apologise for appearing before you in the character of an autobiographist. I never wrote a book in my life. I have not written this, therefore I apologise twice.” So begins The Adventures of The Strange Man, Dr. H. S. Lynn, with a Supplement Showing “How It’s Done” (London, 1873), a rather Strange Book about magic tricks… but also, about theatrical life in the Victorian period, the performance of self in autobiography, world travel in the nineteenth century and, let’s face it, the art of total fabrication.

This book comes to you courtesy of Victorian Popular Culture, a digital collection of archival resources in three closely related areas: Spiritualism, Sensation and Magic; Circuses, Side-Shows and Freaks; and Music Hall, Theatre and Popular Entertainment.

This collection is, in a word, spectacular. Literally. You get page images of the posters, pamphlets, postcards, souvenirs, playbills, scripts, scrapbooks, periodicals, theatrical architecture designs, tickets and photographs that constituted and supported popular entertainment in the “long” nineteenth century (here spanning the beginning of Mesmerism in 1779 through the 1930s)—as well as whole books: memoirs like that of The Strange Man, histories, plays, works on stagecraft, practical guidebooks. You can read straight from the page images or from transcripts of the text. You can learn more about the topics that the collection represents in a series of helpful essays. And of course, you can search or browse the collection.

How can you use these materials? Perhaps you’d like to know more about the theatrical productions that Charles Dickens created with his siblings as a child, to see how such domestic play-acting may have influenced his sense of novelistic structure. The answer may lie within The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England. Or perhaps you’d like to know more about the tableaux vivants performed in private homes in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, and Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth. Were these parlor amusements similar to the tableaux vivants performed in public by professionals? Check out the playbills and clippings for performances at the Vauxhall Gardens in London. Would you like to examine the figure of Harry Houdini within the culture of early 20th-century vaudeville? Look no further: you can read The Sphinx: A Monthly Magazine for Magicians and Illusionists (1902-03), Houdini’s own Handcuff Secrets (1910) and several biographies. Or maybe you’d like to investigate the role of women in the spiritualism movement of the 1840s and ‘50s. You might find it useful to peruse The Celestial Telegraph; or The Secrets of the Life to Come, Revealed Through Magnetism (1851).

Each item in the collection is also listed in the library catalog, so you can use Catalyst to explore connections between our on-site collections and the digital surrogates in Victorian Popular Culture. Perhaps you’d like to see how The Strange Man, for example, compares to The Mysteries of Magic, by Eliphas Levi, at the Peabody? We also have several of the titles listed above in our rare books collections. You could look at both the digital and print versions of Sports and Pastimes, for example. Yeah baby!