(With apologies to Dylan Thomas.)

(With apologies to Dylan Thomas.)

Since it’s poetry month, and since we are a library, well, it seems a good idea to consider some brouillons d’ecrivain!—the writer’s drafts—the manuscripts.

Yes, the poem comes from the poet’s experiences in the world—from the world, then, from the poet’s patterns of interaction, from random conduits of connection. But also, the poem comes from the poet’s poubelle: the trash-can into which he or she has tossed the crumpled papers bearing the cross-outs and erasures of a work-in-progress. (We hope the writer is in fact recycling these discarded papers, and drinks his or her inspirational coffee from a reusable or compostable cup.)

Perhaps this idea of trash-can-as-source seems counter-intuitive. The trash-can holds what is rejected, after all, not the final version that the writer accepts. But if you think like a critic in the mold of la critique genetique (genetic criticism), like the folks at the Institut des textes et manuscrits modernes, what you find in the trash-can is not trash but layers of the poem’s formation. These layers, as they develop and die and evolve, are an energetic source of the force that drives the poem.

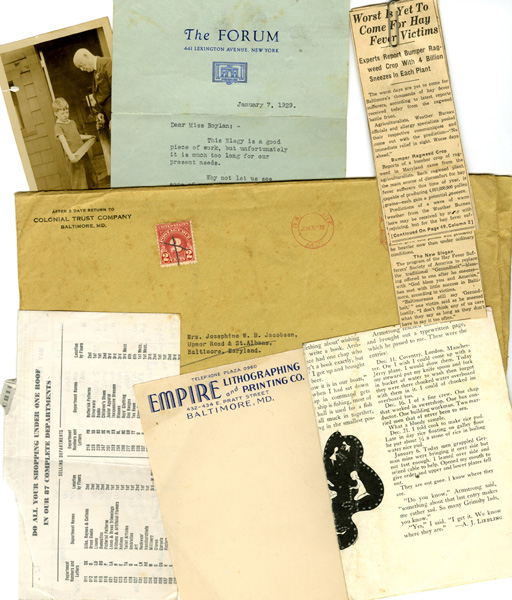

Sometimes these layers may seem… irrelevant at best. The collage above is made up of materials from an old notebook belonging to the Baltimore poet Josephine Jacobsen, a former Poet Laureate, whose papers the Sheridan Libraries have recently acquired. The letter from the magazine Forum tells us they did not want to publish a poem she had submitted. The people in the photo are not unidentified. The newspaper and magazine clippings suggest some of her domestic preoccupations and interests, but no more. The envelope contains bank information. And why did she hold on to blank stationery from the Empire Lithographing and Printing Company?

Sometimes these layers may seem… irrelevant at best. The collage above is made up of materials from an old notebook belonging to the Baltimore poet Josephine Jacobsen, a former Poet Laureate, whose papers the Sheridan Libraries have recently acquired. The letter from the magazine Forum tells us they did not want to publish a poem she had submitted. The people in the photo are not unidentified. The newspaper and magazine clippings suggest some of her domestic preoccupations and interests, but no more. The envelope contains bank information. And why did she hold on to blank stationery from the Empire Lithographing and Printing Company?

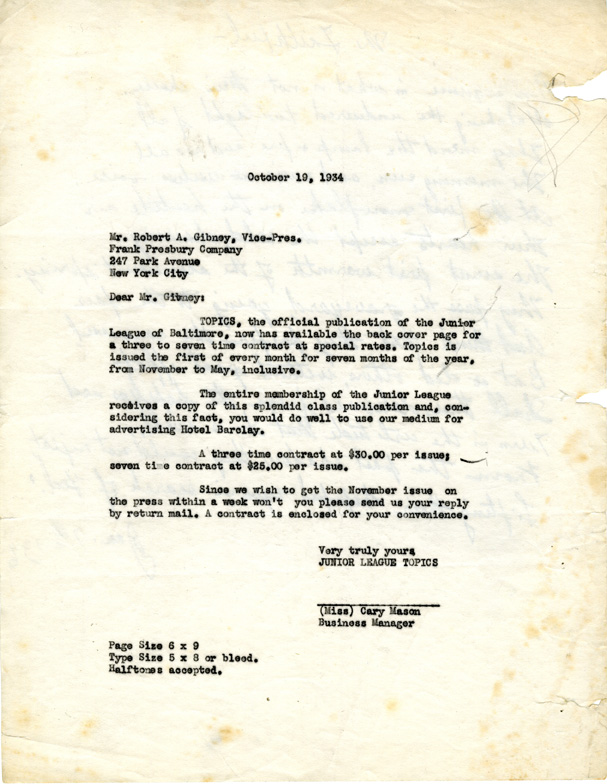

But a poet’s ephemera—what was  perhaps destined for the trash-can but somehow salvaged—can also be richly informative. The letter above, about advertising rates in the Junior League of Baltimore’s magazine Topics, seems like it could have nothing at all to do with poetry. But its verso contains a hand-written sonnet. The residual matter from the “other” parts of a poet’s life bypasses, collides with, works its way into and occasionally illuminates the poetry.

perhaps destined for the trash-can but somehow salvaged—can also be richly informative. The letter above, about advertising rates in the Junior League of Baltimore’s magazine Topics, seems like it could have nothing at all to do with poetry. But its verso contains a hand-written sonnet. The residual matter from the “other” parts of a poet’s life bypasses, collides with, works its way into and occasionally illuminates the poetry.

What will happen to our understanding of the forces that drive poetry when we no longer have the trash-can to raid? All those digital drafts overwritten, or degrading on floppy discs, flash drives and servers? Poets, preserve your electronic poubelles!

And speaking of poems: don’t forget to enter the library’s haiku contest! Deadline is midnight this Friday, April 15.

Bon effort!