Sidney Lanier was a flautist. Sidney Lanier was a Confederate soldier, captured by the Union and imprisoned at Point Lookout, Maryland, where he contracted tuberculosis. Sidney Lanier was a hotel clerk and tutor. Sidney Lanier was a father. Sidney Lanier was a professor at Johns Hopkins University.

And Sidney Lanier was a poet. Many of his poems reveal his musical training and his ear for orchestration—poems like “The Dove: A Song.” But aside from Lanier’s checkered history and literary ambitions, how did “The Dove” come to be?

One way to understand a poem is to investigate the various stages of its composition and publication—if you are lucky enough to have access to those materials. In this case, you are! The Sheridan Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Department has letters, manuscripts, notebooks, magazine pieces and books written by Lanier, who is considered a “minor” poet today but was much admired in his lifetime. (You can read about our manuscript holdings in the finding aid for The Sidney Lanier Papers.) Using these manuscript materials in conjunction with other library and digital resources can lead to surprising insights.

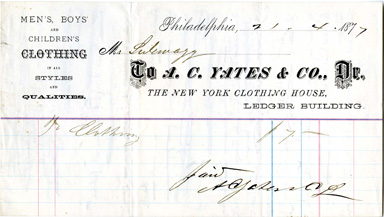

It all starts with this receipt from a Philadelphia clothier, from April 1877.

It’s just a scrap of paper that would have been thrown away long ago—except that somehow it came into Sidney Lanier’s possession. He used the back side to sketch out his first ideas for “The Dove”: the “tender heartbreak” of the “Morn” and the “Spring.”

Where did he go from there? Read on!

In 1876, Lanier moved his family from Macon, Georgia to Baltimore, where he was thriving. His first book of poetry was published in 1877; in that year he was working as first flute for the Peabody Orchestra and preparing to give lectures on Shakespeare at the Peabody Institute. (You can read a short biography of Lanier in The Encyclopedia of American Poetry, available through Literature Online, or one from the Baltimore Literary Heritage Project.) But at some point that spring he made a trip north.

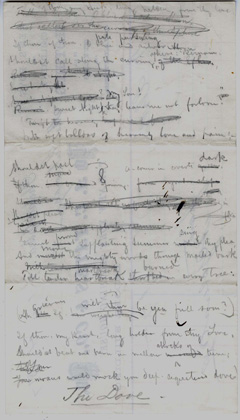

After scribbling down his first ideas for “The Dove,” Lanier copied and revised.

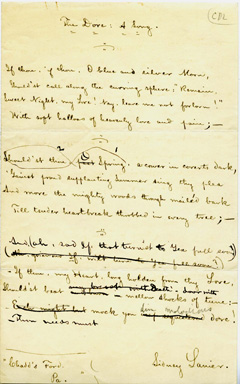

This time, he identified the location of the poem’s origin: Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania. Even today, Chadd’s Ford is a bucolic area 25 miles outside of Philadelphia, where the Baltimore Pike crosses the Brandywine River. It’s also where, in 1777, General George Washington lost the Battle of Brandywine—a turning point in the American Revolutionary War that allowed the British to capture Philadelphia. Imagine the Civil War vet Sidney Lanier on his way home from Philly in late April 1877; he is on the site of a terrible losing battle from a century before, but he is surrounded by  the loveliness of a rural springtime. How can he represent all that—the strange coincidence of past war and present tranquility? The poem begins by addressing the “Morn” and the “Spring,” but it ends with the dove, the symbol of peace.

the loveliness of a rural springtime. How can he represent all that—the strange coincidence of past war and present tranquility? The poem begins by addressing the “Morn” and the “Spring,” but it ends with the dove, the symbol of peace.

Still, as you can see from its many crossed-out lines, Lanier wasn’t satisfied with the poem’s last stanza. It seems he wanted to put more emphasis on the dove by giving it a stanza of its own. You can read the final version of the poem, as it was published in May 1878 in Scribner’s Monthly, through American Periodical Series. You can read the poem in the pages of the actual magazine (volume XVI). And you can read it in the book—in the original or on Google Books—that was published after Lanier’s death in 1881 from his war-time tuberculosis.

You can also recreate, in a modest way, the springtime excursion that led to “The Dove” —by visiting the monument to Sidney Lanier on the Homewood campus.