The National Council on Public History (NCPH) hosted its annual conference in Montréal, Canada, earlier this year. The theme, Solidarity/Solidarité, guided the panels and programming, asking attendees to consider how to best nurture our connections with the work we do. In our first post about the NCPH 2025 Conference, Allison Seyler, program manager for Hopkins Retrospective—the university-wide public history initiative that explores the history of Johns Hopkins University and shares it in meaningful ways—wrote about her experiences during the conference and how they fit into the concept of solidarity.

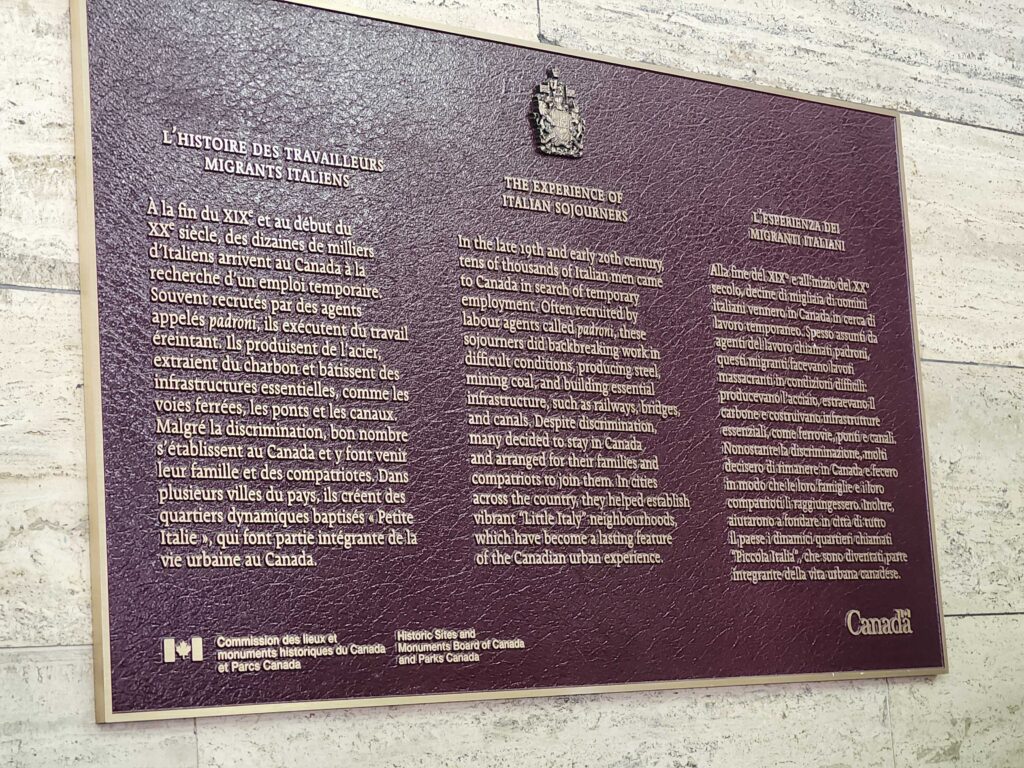

As digital content & outreach coordinator for Hopkins Retrospective, I also attended the conference, and want to offer my takeaways. I attended over half a dozen sessions, many of them offering new perspectives on public history work. Among the most impactful for me were a session on a community-engaged model for developing school programs about slavery, a reflection on an exhibit and event on Black and African Canadian hair stories at the Canada Science and Technology Museum, and a tour of historical commemoration via plaques and statues in downtown Montréal.

In addition to hearing about others’ work, we were also able to share the work we do through Hopkins Retrospective in two sessions. Allison and I presented together at “Engaging Communities in Critical University Histories.” We shared a roundtable with JaJuan Johnson from The Lemon Project and Kirt von Daacke from the University of Virginia, a fellow member of the Universities Studying Slavery Consortium. While not physically present at the conference, Angela Koukoui contributed to the proposal and preparation of our roundtable, representing her past experiences with the University of Maryland’s 1856 Project and Center for Archival Futures.

Our roundtable focused on how public history projects housed in universities can ethically engage with local communities. In the first half of the roundtable, we shared our experiences engaging with and working in solidarity with local community stakeholders. In the second half, we broke the audience into small groups and discussed shared issues and brainstormed different ways to enhance community collaboration and power sharing.

I also represented Hopkins Retrospective in a session titled “Solidarity in Our Storytelling: Lessons in Collaborative Historiography.” I sat down with three other panelists to discuss projects that consider how public history makers and the field as a whole have told stories and written history either with subjects as co-writers/participants or in highly collaborative modes that defy traditional and/or solo author/researcher approaches. My fellow panelists’ topics spanned from the challenges and joys of documentary filmmaking in a closed community to local history organization collaborations with college students and building an oral history project about university librarians. I spoke about my experiences using social media, specifically Hopkins Retrospective’s Instagram, as a tool for meaningful collaboration with your community and its capacity to elevate historical content.

Lastly, Joseph Plaster, curator in public humanities and director of the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center, also sat on a roundtable at the conference titled “Activating Queer/Trans Archives: Oral History as Public History.” The roundtable brought together LGBTQT2+ oral history organizers from the U.S. and Canada. The session interrogated how the ethics of care shaped the interview process, how they have challenged “traditional” ways of practicing oral history, the tensions of reaching a broader audience and safeguarding communities, and how best to activate queer archives for education, social justice, and public engagement.

The NCPH’s annual gathering of public historians, archivists, scholars, community members, and those set on enriching their communities through history from around the world offers a much-needed hub for inspiration and network building. The bilingual invitation for the conference also opened the floor for understanding the context of many of our projects beyond our institutional boundaries. We have the power to transform our communities through the marriage of history and solidarity/solidarité.